Keep On Believin'

Joe Louis Walker Is A Witness To The Blues. Ask Him.

By David McGee

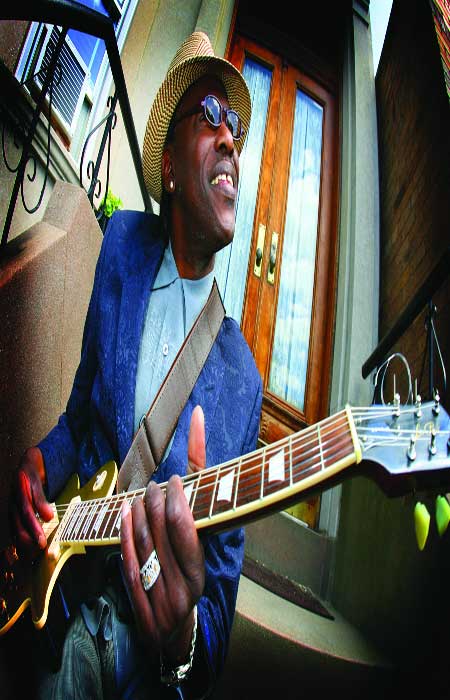

Joe Louis Walker: Witness to the blues, master of context

Photo by Al PereiraIf you're looking for a straight answer, Joe Louis Walker is not your man. Oh, he's truthful in his responses, straight in that sense. But how he gets to the point is, well, roundabout. There's no prevarication about what the meaning of "is" is, but to ask a question of Joe Louis Walker is to embark on a journey. He'll address the topic at hand directly but, being big on context, he takes his interlocutor into the deeper history that brought him to a particular point in time. See, he's an educated man, with a degree in Music and English from San Francisco State University that he earned after retiring to academia in the wake of the 1981 death of his friend and musical colleague (and roommate) Mike Bloomfield, who, like JLW, was something of a legendary blues guitarist, as readers might recall. He knows how deceiving and misleading simple answers can be; better still, he knows the full story can provide a richer experience than the short version.

That's because Joe Louis Walker knows the full story. He's traveled the blues highway since rising to prominence in the Bay Area blues scene as a 16-year-old in 1965. Influenced by great blues guitarists and entertainers such as T-Bone Walker and B.B. King, and equally gifted blues piano players such as Meade Lux Lewis and boogie woogie king Pete Johnson, San Francisco native Walker (who now makes his home in Westchester, NY, a few miles north of New York City) early on developed a signature sound on his Fender Strat marked by his stinging, lyrical lines and elegant, economical phrasing. He's played with a virtual Blues Encyclopedia of towering 20th Century musical giants from a range of disciplines, from John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters, Otis Rush and Thelonious Monk to the Soul Stirrers, Jimi Hendrix, Nick Lowe and Steve Miller (among many, many others, as the expression goes). Following Bloomfield's death, he immersed himself in one of his first loves, gospel, by performing with the Spiritual Corinthians gospel quartet. He returned to the blues on his first solo album, Cold Is the Night, in 1986, and has since wasted no opportunity to fuse the blues with other musical styles, as on his 1994 album, JLW, which teamed him with Chicago blues legend James Cotton but also with jazz virtuoso Branford Marsalis and the Tower of Power horns. Or 2002's In the Morning, which did some heavy mining in the Memphis vein, on the spiritual "Where Jesus Leads," on the gritty, powerhouse R&B of "Strange Love," on the slinky groove he found in the Stones' "2120 Michigan Avenue" (the song itself being a tribute to Chess Records, from whence JLW drew much inspiration as well), and in the Latin flavoring of "You're Just About to Lose Your Crown." One of the acknowledged gems in Walker's catalogue came in 2002 (a productive year for the artist that found him releasing three new albums in little more than 12 months' time) with the ambitious, infectious Pasa Tiempo, a meshing of blues, soul and R&B with a Latin foundation, working on songs by Van Morrison, Otis Redding, John Hiatt and Boz Scaggs supplemented by three powerful Walker originals. Those included two extended workouts with Latin grooves, "Barcelona" (five minutes-plus) and "Pasa Tiempo" (clocking in at close to four-and-a-half minutes), and the seven-minutes-plus "You Get What You Give," a smoky, churning, downcast blues lament aimed at a faithless lover, with Walker's accusatory vocal bolstered by Ernie Watts's searing sax solos and Wally Snow's atmospheric, noir-ish vibes before the tune breaks into a brisk strut at the six-minute mark, allowing for an exhilarating improvisational discourse between Watts, Snow, percussionist Master Henry Gibson and drummer Leon Ndugu Chancler, with Walker adding only a tasty, compact guitar filigree at the end.

Now comes the appropriately titled Witness To the Blues, which finds JLW on the Canada-based Stony Plain label. With an able assistant from producer/guitarist Duke Robillard, Walker fashions an invigorating jaunt into blues country, working that Memphis-Muscle Shoals-Clarksdale axis for all it's worth with a horn-bolstered band, a variety of guitars at his disposal and a stirring collection of songs, more than half of which he penned, ranging from mean woman blues to gospel-rooted pleas.

History, personal and otherwise, runs rampant on the tracks: there's a Sly Stone "Take You Higher" horn quote energizing the album opener, "It's a Shame"; the rockabilly-blues fusion of his own "Midnight Train," which blends the doghouse bass and fierce rhythm of Elvis Presley's Sun side with the grit and urgency of Junior Parker's original Sun recording, and even references a memorable lyric from the source song at the end; and twice on the record he makes reference to being "100 percent more man" (including in a grinding, wailing blues near the end titled, yes, "100% More Man," concerning a young woman, which would seem to be a testosterone reduction in deference to the late Bo Diddley, who famously boasted of being "500 percent more man." One of the compelling, tender moments comes in his reprise of the Peggy Scott/Jo Jo Benson salacious classic, "Lover's Holiday," with Walker and Shemekia Copeland engaging in a sultry duet reminiscent of heated couplings on disc by Otis Redding and Carla Thomas, an impression reinforced by the funky Stax-style backing keyed by a scratchy guitar and Bruce Katz's voluble organ support (a symbolic tipping of the hat to the three Walker albums co-produced with Steve Cropper?). Adding depth to the subject matter is Walker's powerful, churning "Witness," a Muscle Shoals-styled mussing of the gospel/soul boundary line in which he reflects on the numbing number of lost, lonely, needy souls he sees all around him, even while admitting to personal spiritual failings en route to "my way back home." Describing his quest in anguished detail, Walker shouts an aggrieved testimony over a rich musical backdrop percolating along at a steady, midtempo march but escalating in intensity as the song evolves, culminating in a grand explosion of organ, piano, guitar and thunderous drums as Walker howls, "Raise up! Raise up!" in exhorting his listeners to reach out to the less fortunate among them, an appeal as inspiring as Springsteen's "Rise up! Rise up!" in "The Rising," and a forceful reminder to boot of Walker's deep roots in gospel music. Echoes of Jimmy Hughes permeate "Keep On Believin'," which in title and style comes out of the church and heads for secular ground (it's a man's vow to stay true to a woman whose feelings for him are uncertain), again with Katz's emotive organ dominating the feel of the track and Walker injecting trebly, anxious guitar lines and being shadowed vocally by an insistent chorus in call-and-response mode. It's always a treat to hear JLW do an acoustic number, and this album's suggestive Delta blues, "I Got What You Need," is a righteous, rhythmic workout between the artist and his producer, playing in tandem and trading bristling solos, Walker on slide, Robillard picking, and JLW expressing to his reluctant paramour his desire to be "your 100 percent man," a theme fully developed two songs later.

So in many ways Witness To the Blues is not an unusual Joe Louis Walker album, but its energy is of a different order. Walker agrees, and points out "we just went in the studio and played, not a whole bunch of overdubbings, not a whole bunch of bells and whistles."

Now, the context: "You know what it is?" he begins. "I've worked with great producers—Tony Visconti, Steve Cropper. I'd been off tour and I said, 'Let me call some of my partners.' So I called John Hammond, we were playing phone tag; I called Larry Coryell, and Larry moved to Florida; something told me to call Duke Robillard. Me and Duke have done a lot of playing together, we played Australia together on several occasions, we played B.B. King's club, and so I told Duke I had the songs and was going to be demo'ing 'em and I needed to get somebody to produce the record. A light went on in my head and I said, 'Hey, man, would you be interested in doing something?' And Duke said, 'I'd be honored.' Boy, did I get lucky. So just like Cropper or Tony Visconti, he never tells you what you can't do. If you have a disagreement about a particular part of a song, Cropper would say, 'Take a tape home, listen to it.' Every time I'd bring it back the next day I'd tell Cropper, 'Don't ever listen to me.' He's so gentlemanly; you gotta pull teeth to get Cropper to tell you how things are done. Same with Duke, same with Scotty Moore, same with Ike Turner. They have that thing-they've been in the studio, especially Cropper and Scotty. Those guys are what I call 'studio rats'-they made shit work that wasn't even invented! Now everybody takes it for granted. So I was real fortunate."

Ah, yes. Wax enthusiastic to Walker about the sultriness of Shemekia Copeland's duet vocal with him on "Lover's Holiday," and he not only agrees but also offers insights into the art of singing, and you find you might never have figured on someone identifying Stevie Ray Vaughan as a gospel singer. Well, listen to the man: "Yeah, I knew Shemekia's dad. [Note: the late Texas blues great Johnny Copeland] I played on her first record, and Shemekia's only going to get better. She's almost at the top of her game now. She's smart. As good as she sings, she's taking music lessons. I did the same thing about 15, 20 years ago, just to be able to call up certain things, like learning how to sing from your stomach. It takes discipline to sing from your stomach. You hear somebody like Bob Dylan, I love Bob Dylan, he sings from his nose. But then when you heard Nashville Skyline, he was singing from his stomach. You know he'd been in that wreck, and you gotta breathe in the hospital. Now Bob's back to singing the way he used to, but he's still Bob Dylan. He learned how to sing right. Same thing with Elton John—he came out and said it. It takes time to learn. I give him credit for doing that. But good gospel singers sometimes sing from their nose too—like Stevie Ray, when he needed to get a point across. But you hear someone like Little Milton, or Otis Rush, or B.B., and they're singing from their stomach. That's why it sounds so powerful. You want a big sound? Open your mouth. That's why when you see someone like Pavarotti and he's hitting a high note, a hard note, his mouth is open—if you make a mistake, make it loud and proud. It's like playing guitar. I don't like when guys chop the notes off. They do that because they've run out of breath. Then you hear some singers who can just hold a note forever."

Take him into gospel territory proper to discuss his two songs in that vein on Witness To the Blues-"Witness" and "Keep On Believin'"—and history begins to curl in on itself, but it starts way back at the beginning of his career. He was 16 when he wrote "Witness," but he considered it incomplete until he added the gospel call-and-response chorus for these sessions that he considered the song complete. "That's what I'd been waiting for since I was 16," he says. "I just never found a place for it. On Pasa Tiempo I did a song called 'Barcelona.' I wrote that when I was 19 and I could never find a place for it. Pasa Tiempo lends itself to a different part of me. If you ever notice on that album, I don't take but two guitar solos; I do most of the singing. I had Phil Upchurch do a guitar solo on 'You Can't Sit Down,' which was an epiphany, and I was fortunate enough to have Matthew Henry, the guy Curtis Mayfield took when he left the Impressions and played all the stuff on the Superfly soundtrack, the percussionist; I had my home boy Barry Goldberg (Hammond organ); I had Ndugu Chancler, who is really Leon Ware, who played on Off the Wall and all the Michael Jackson stuff. But the biggest thing is I had my partner Ernie Watts on saxophone. We had always talked about making a record. And it was a big deal."

Talk about "Witness" leads to background on a project that might really be something to behold if it ever comes to pass, a gospel album pairing Walker with the Jordanaires and the Blind Boys of Alabama. It's developed no further than a demo recording, but it's a live prospect. "I told Ray Walker of the Jordanaires about my idea about recording with the Blind Boys and he said, "Me and Clarence Fountain were talking about that about a month ago. But it would be good for you to do it, Joe. Write some songs.' So I'd written a song called 'Soldier for Jesus' for a record I did called New Directions. Ray heard the song and just flipped. He says, 'This is what I'm talking about-it's not preachy,' and it's true, I am a soldier for Jesus. I'm not a Bible thumper but I do believe that somebody did die for the rest of us. It wasn't George Bush, that's for sure.

"But that brought us all together, and I cut a demo of 'Mary Don't You Weep' in my funky way-rockin'-and I did my version of 'Wade In the Water.' I had to get everybody in the same place at the same time. But [Blind Boys lead singer] Clarence Fountain is on a dialysis machine, and without Clarence, it's like the Temptations without David Ruffin. I liked Dennis Edwards, but if you give me David Ruffin signing, 'I know you gonna leave me...' you know, I'll listen to that other shit later."

And what about that "100 percent more man" declaration? Turns out it's only a partial tribute to Bo Diddley. The bigger picture is more resonant with moving history. "It's a cross of the 'man' songs," Walker says. "'Mannish Boy,' Muddy Waters; 'I'm a Man,' Bo Diddley, he's 500 percent more man. That's what it is, that's where it came from. 'I once had a little girl/she didn't understand/all I wanted to do/was be 500 percent more man.' Well, that's like Muddy—'Can't lose what you never had/but I'm a man'—the mannish boy thing. When Martin Luther King died, there was a garbage workers strike going on in Memphis. If you look at the videotape, all the garbage workers have signs that say, 'I'm a man.' You would think it's from the Civil Rights Movement, but when they were asked, no, it was from the Muddy Waters song, 'I'm a Man.' Bo Diddley had 'I'm a Man,' Muddy had 'Mannish Boy,' which is a black saying for 'you think you're mannish,' and it's also for a woman who's just like a man—'she looks real mannish.' So Muddy took it home in our vernacular; Bo Diddley took it home so that people like the Stones and you could understand it. But the Muddy one, the show he used to do with that was incredible-take a bottle of beer, put it in his crotch, take it to the front of the audience, open it and let it spray all over the audience. That was Muddy. Muddy never lost the power. He puts us all in the mind of an Egyptian king. Muddy accepted everybody. He schooled Mick Jagger; he schooled my home boy Mike Bloomfield. He took Johnny Winter as a second son. He may have inspired and influenced even more artists than B.B. His music was so inclusive; everybody did a Muddy Waters song. Muddy was a direct link, from Son House to Muddy to Bloomfield to Clapton to all the rest. Bo Diddley the same way. John Lennon would have been a skinhead, Keith Richards would have been a dope fiend, but when they heard that music it changed their lives and gave them a purpose. Classical music's great, but you have to be a virtuoso; jazz is great but you have to have a musical thesaurus sometimes; rock 'n' roll, which Chuck Berry invented, is all right—that gave everybody a purpose too. But Muddy gave everybody a bigger purpose."

'Muddy Waters,' says Walker, 'gave everybody a bigger purpose.'

Now that's a witness to the blues. Next up is a project 15 years in the making: an album with Johnny Winter, who's been battling severe health problems in recent years stemming form his albinism, but is, according to Walker, up to making their long deferred dream a reality. Sessions will begin this month in Winter's studio at his Connecticut home. Even here, history informs the process.

"That's my partner," Walker says of Winter. "I think he deserves a medal for what he did with Muddy, and he's one of the most sensitive musicians I know. He's like a brother to me. For him to want to do this with me is flattering."

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024