CROSSING OVER

By David McGee

The original Four Tops (from left): Renaldo 'Obie' Benson, Lawrence Payton, Abdul 'Duke' Fakir, Levi StubbsLEVI STUBBS

June 6, 1936-October 17, 2008In England Levi Stubbs is revered as a soul man on a par with Jackie Wilson and James Brown. It's a shame his name is not a household word in America, but that's more due to his own humility than to his fellow countrymen's ignorance or inconsideration. For a couple of generations of classic soul music fans, the name Levi Stubbs (who was Jackie Wilson's cousin) may have been a long time in surfacing, but his voice, and the name of the group he fronted, The Four Tops, well, everyone knew it and them. A big, gritty baritone with a sweet, tenor-like tone at times (he was the soul music iteration of gospel's Julius Cheeks, the Sensational Nightingale's great lead singer), his was a voice that would stop listeners in their tracks when they heard it coming over the airwaves, as it did this writer on several occasions. When Levi roared, you listened, and you learned. I still remember a cold walk home after high school basketball practice in early '65, a little tinny transistor radio tucked in my coat pocket, an earpiece in one ear, and the first pounding chords of "Just Ask the Lonely" emerging, along with the beautiful, rising strings and a soaring female chorus, before Levi enters, caressing the tender opening lyrics in a soothing tone—"When you feel that you can't make it all alone/Remember no one is big enough to go it alone"—before crying—crying—out the title sentiment-"Just ask the lonely/They know the hurting pain/Of losing a love you can never regain..."— and, line by line, peeling away the avuncular ruse until he's declaiming to the heavens and confessing to the listener the source of his intimate knowledge of the topic at hand:

"Just ask the lonely/Ask me-e-e-e/I'm the loneliest one you will see"

That was Levi Stubbs, a voice that beseeched you to remember where you were and what you were doing when you heard it. A voice that unlocked the mystery of life, explained the unexplainable, made spirits take flight, or allowed you a moment's self reflection on all that mattered.

Levi Stubbs was some kind of man. Not merely a great singer—some kind of man. He never considered himself bigger than the group and resisted efforts to bill it as Levi Stubbs & the Four Tops, although it inevitably did become that. He remained a staunch ambassador for the city of Detroit to the end of his life. When Motown moved to the west coast, he preferred to stay behind in the Motor City, his home. Abdul "Duke" Fakir, the only surviving member of the original quartet, told Billboard.com's Gary Graff that Stubbs "was dedicated to us. He had many chances and many offers to be lured away into his own solo world, but he never wanted that. He said, 'Man, all I really want to do is sing and take care of my family, and that's what I'm doing, so all is well. Everything else that doesn't include you guys, it doesn't mean a thing to me.' That kind of character and commitment is really hard to find these days."

The members of the Four Tops all claimed Detroit's North End as their neighborhood. Stubbs and Fakir teamed together in a group while attending Pershing High School; childhood friends Renaldo "Obie" Benson and Lawrence Payton attended Northern High together. The four boys met and started singing together at a friend's birthday party in 1954, and were soon performing as The Four Aims, a name they changed to avoid confusion with the popular Ames Brothers. The Four Tops began touring with the Billy Eckstine revue in the early '60s, and in 1963 were signed to their friend Berry Gordy Jr.'s Motown label. From 1964 to 1988, recording mostly for Motown but also for ABC Dunhill, Casablanca and Arista, the group notched 24 Top 40 hits, including two #1 singles, 1965's "I Can't Help Myself" and, in arguably its finest moment on record, 1966's epochal "Reach Out I'll Be There." The group's first Top 20 single was 1964's "Baby I Need Your Loving," a performance bristling with the driving intensity and soulful urgency of a good gospel house wrecker. Motown founder Berry Gordy Jr. later recalled his and his staff's reaction to hearing the record for the first time: "Levi's voice exploded in the room and went straight for our hearts. We all knew it was a hit, hands down."

The Tops of course were aided by the stalwart Motown house band, and blessed with great songs from the seemingly inexhaustible well of the Brian Holland, Lamont Dozier and Eddie Holland team. It was Stubbs who made classics of everything he sang. "He had such power," Fakir said. "He had a baritone voice and a tenor range. He could do anything with his voice. He could take you anywhere with it. He could take you to a love scene. He could take you dancing. He could take a great old standard and make you feel like you're right there in that song. Just an amazing voice, an amazing interpreter, an amazing man."

In later years Stubbs found other uses for his voice besides singing. In 1986 he voiced the role of the carnivorous plant Audrey II in the movie musical version of Little Shop of Horrors, and in 1989 served as the voice of Mother Brain in animated TV series, Captain N: The Game Master.

In 1995 Stubbs was diagnosed with cancer and later suffered a stroke, which prevented him from touring. Fakir said he had visited Stubbs (who was godfather to Fakir's oldest child) a week prior to the singer's death "and he looked healthier. His face was fatter and he was smiling and he was in good spirits. I really thought he'd pull through longer than he did." On October 17, Stubbs died in his sleep in his Detroit home. He is survived by his wife Clineice, whom he married in1960, and five children.

On film Stubbs's voice was put to best use in the final scene of Michael Schultz's 1975 feature, Cooley High, a poignant and loving look at a group of inner city black teens in Chicago in the early '60s as their high school years wound down (the movie was sometimes referred to as "the black American Graffiti"). Following the funeral of his senselessly murdered friend "Cochise" (played by Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs), "Preach" (Glynn Turman), an aspiring poet and screenwriter bound for Hollywood, visits the open gravesite after everyone has gone home. From his jacket he pulls a bottle of cheap wine, and takes a sip in Cochise's honor—after pouring some on the ground "for the dudes who ain't here"—and recites a new poem he's composed in memory of their time together. Frustrated with himself because the poem "don't rhyme," he says goodbye, slings his backpack over one shoulder and sprints away, onto the road, into his future, as if he can't get there, and past the pain, soon enough. With Preach's image freeze-framed in mid-stride, the Motown soundtrack erupts with, "Now if you feel you can't go on/because all your hope is gone/and your life is filled with much confusion/until happiness is just an illusion/and your world around is tumbling down/now darling, reach out, just reach out for me/I'll be there/with a love that will shelter you..." It was the whole story in a nutshell, the spiritual connection the friends share even in death, the love, the commitment, writ large by the conviction in and solace of Levi Stubbs's testifying.

Here's one for the dude who ain't here.

***

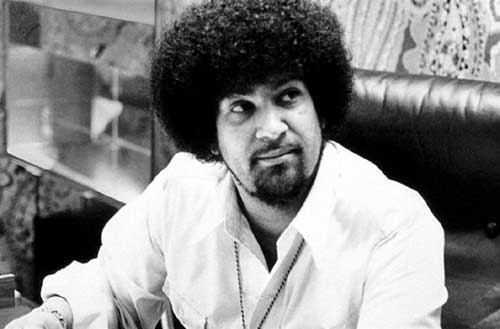

NORMAN WHITFIELD

May 12, 1940-September 16, 2008

A broke down car turns out to have been one of the best things that ever happened to Motown Records in its early days. The car belonged to the family of Norman Whitfield, who was a teenager when the Whitfields settled in Detroit after their car refused to go any further. As a songwriter and producer, he would become one of the architects of the pop-soul Motown Sound, and in later, rock- and funk-laced productions would pave the way for artists such as Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder to use their music as a platform for addressing the social issues affecting America as a nation and black Americans in particular.

Born in New York City on May 12, 1940, Whitfield was in his late teens when he landed in Detroit; at age 19 he was working for Thelma Records, and shortly thereafter made his way to Motown Records, gaining employment first as a tambourine player and then in the company's quality control department, where decisions were made as to which songs the label would release or can. His next step up the ladder was to join the house songwriting staff, and he co-wrote (often in tandem with Motown artist Barrett Strong, who had recorded the label's first hit, 1958's "Money") "Pride & Joy" for Marvin Gaye, "Needle In a Haystack" for the Velvelettes and "Too Many Fish In the Sea" for the Marvelettes. In 1966 he assumed the main producer's role for the Temptations, supplanting Smokey Robinson after Whitfield's song "Ain't Too Proud To Beg" outcharted Robinson's "Get Ready." From 1966 to 1974 he steered the Temptations' recording career and, following the 1968 departure of lead singer David Ruffin and the subsequent ascension of Dennis Edwards, took the group into a grittier, darker, socially conscious direction, painting vivid pictures in sound with productions that employed ample swatches of psychedelic rock frenzy and the emerging hard-edged funk sound pioneered by Sly Stone. In this "psychedelic soul" period of their history, the Tempts earned Motown its first Grammy in '69 for the 1968 single "Cloud Nine" and another in '73 for the dazzling "Papa Was a Rolling Stone," which was also one of the first songs — if not the first — to specifically address the epidemic of absent fathers in black families. In 1970 he wrote two searing topical songs that captured the turbulent zeitgeist of the Vietnam era, the Temptations' "Ball of Confusion" and Edwin Starr's "War"; in 1971, the Undisputed Truth had a hit with a Whitfield song originally recorded by the Temptations, "Smiling Faces Sometimes," a damning, and cautionary, observation about duplicity and skullduggery. In 1973 he left Motown and formed Whitfield Records, taking the Undisputed Truth with him. The label's biggest hit was the 1976 theme song to the film "Car Wash," by Rose Royce, a group whose members had been Edwin Starr's backing band on "War." The Car Wash soundtrack earned Whitfield a 1977 Grammy Award for Best Score Soundtrack Album, but the label soon folded. In the early '80s he returned to Motown, producing another hit for the Temptations, 1983's "Sail Away," and the soundtrack album for the film The Last Dragon. In 2005 he pleaded guilty for failing to report his earnings on royalty income of more than $2 million from the years 1995 to 1999. He escaped imprisonment due to his declining health, and was instead sentenced to six months house arrest and fined $25,000. In the final months of his life he was reportedly bedridden at Los Angeles' Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, where he was being treated for diabetes and a variety of other ailments. He died on September 16, 2008, from heart and kidney failure stemming from diabetes, according to his daughter, Irasha Whitfield.

In addition to his daughter, Irasha, of Los Angeles, Whitfield is survived by four sons, Norman, of Los Angeles; Michael, of Toluca Lake; Johnnie, of Atlanta; and Roland, of Murrieta, Calif.; a brother, Bill, of Los Angeles; eight grandchildren; and a great-grandchild.

***

DEE DEE WARWICK

September 25, 1945 - October 18, 2008

Dee Dee WarwickSoul singer Dee Dee Warwick (nee Delia Mae Warrick) never attained the critical or commercial heights her sister Dionne enjoyed, but she never lacked for respect, or work. An R&B Foundation Pioneer Awardee, she made regular visits to the soul and R&B charts in the 1960s and 1970s with songs such as "She Didn't Know (She Kept On Talking)," "Foolish Fool" and the original version of Gamble and Huff's "I'm Gonna Make You Love me," which was a #13 R&B hit for the artist but is better known as a 1968 pop hit (#2 for two weeks) by Diana Ross and the Supremes in collaboration with the Temptations, and she was twice nominated for a Grammy Award. Before going solo she was an in-demand backup singer for some of the top soul and R&B artists of the day, including Aretha Franklin, Nina Simone, Solomon Burke and Wilson Pickett, and she also toured with her sister Dionne, most recently on an European tour of Dionne's one-woman autobiographical show, My Music & Me.

Born in Newark, NJ, Dee Dee and Dionne began singing together as teenagers in the late 1950s. At the urging of her aunt Emily (better known as Cissy Houston), she joined Dionne in the New Hope Methodist Church choir in East Orange, NJ. In 1960 Dionne formed the Gospelaires with Dee Dee and Cissy Houston as members; Dee Dee and Dionne also sang with the Drinkard Singers, an established gospel group whose members included various Warwick aunts and uncles and was managed by Dee Dee and Dionne's mother. When the Drinkards were asked to provide backing vocals on a recording session by Savoy recording artist Sam "The Man" Taylor, but were unavailable, the Gospelaires took their place and made their recording debut on Taylor's "Won't You Deliver Me." Session work ensued with Nappy Brown, Big Maybelle, Connie Francis, Gene Pitney and the Drifters. During the Drifters session Dionne was recruited by Hal David and Burt Bacharach, signed to Scepter Records as a solo artist and became an international star. Dee Dee continued on with the Gospelaires, but went solo herself in 1963, recording "You're No Good" for the Jubilee label with producers Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller. The song would later be a big hit for Linda Ronstadt, but Dee Dee had to wait until 1965 for any kind of chart success on her own, with "We're Doing Fine" for Mercury's Blue Rock subsidiary (where she was produced by R&B great Ed Townsend), followed by "I Want To Be With You" for Mercury proper, which became her biggest U.S. pop hit with a #41 chart peak (#9 on the R&B chart). In 1970 she was nominated for a Grammy for her Atco recording, "She Didn't Know (She Kept On Talking)" (#9 R&B, #70 pop). Although she struggled for Stateside solo success, Dee Dee consistently charted well in England and gained a devoted following among soul aficionados there, who admired her gritty, straightforward singing style. She gave up her solo career after cutting a single, "Funny How We Change Places," for RCA as "Dede Schwartz" in 1976.

In addition to Cissy Houston, her relatives include Whitney Houston, a cousin. No cause of death was reported, but Warwick had been in failing health in recent months. She died in a nursing home in Essex County, NJ, with Dionne at her bedside. She was 63 years old.

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024