Crossing Over

By David McGee

***

More Bass!

Jerry Wexler

January 10, 1917-August 18, 2008

Soul music lost two giants in August with the passings of Isaac Hayes and Jerry Wexler on the 10th and 18th of the month, respectively. Hayes died of an apparent stroke (he had suffered a serious stroke in 2006 that had affected his speech and memory) while exercising in his home outside of Memphis. Age 65 at his death, he would have celebrated his 66th birthday on August 20. Wexler died of congestive heart failure at his home in Sarasota, Florida. He was 91.

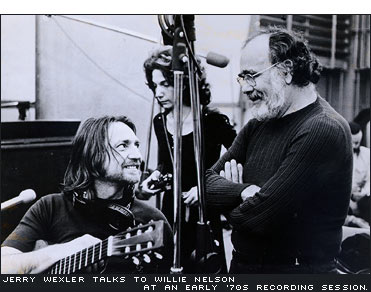

Jerry Wexler was an old school record man who could not play an instrument himself or read music, but knew and could articulate what he thought an artist should be doing. Rarely did his instincts lead him astray. Born in New York City on January 10, 1917, he graduated from Kansas State University (then known as Kansas State College of Agriculture) in 1936 following a spotty academic career and a stint in the armed services. At KSU his education outside the classroom was more useful than his degree studies: there he was exposed toa variety of rural music, and he was close enough to Kansas City, MO, to visit and soak up its lively music scene, which at the time was in full, boogie woogie flight, thanks to Joe Turner, Jay McShann, Pete Johnson and others.

In 1949 he joined Billboard magazine as a reporter and famously coined the term "Rhythm and Blues" to supplant the then-accepted term for music made by black artists, "Race Records." He also encouraged artists he liked, and wasn't shy about dispensing advice, as when he hummed the song "The Tennessee Waltz" to a young Patti Page and suggested she record it. Her rendition sold three million copies. In 1953 he joined Atlantic Records, after being wooed by its founder, Ahmet Ertegun, when Ertegun's partner, Herb Abramson, went into the Army. Wexler and Ertegun proceeded to build Atlantic into the gemstone of American independent labels, with a roster of towering artists, including Joe Turner, Ruth Brown, LaVerne Baker, The Coasters, The Drifters and, Wexler's favorite, Ray Charles, to whom he gave free reign in the studio to follow his own musical instincts, resulting in some of the most important recordings of the 20th Century after Charles dropped the Charles Brown affectations that had marked his records for the Swingtime label and fused gospel and blues in the songs "I Got A Woman" and "This Little Girl of Mine" (which prompted a scolding from bluesman Big Bill Broonzy, who decried Charles's "mixin' the blues with spirituals," saying, "That's wrong. He's got a good voice, but it's a church voice. He should be singin' in church."). At the time Wexler joined the company in 1953 it was grossing under $1 million a year; in 1967 its grosses amounted to $22.7 million.

In the 1960s, when Ertegun was gravitating to rock 'n' roll, Wexler embraced the emerging black music coming out of the southern states, striking up a distribution deal with Memphis's Stax label and producing sessions in Memphis and it's sister city in soul, Muscle Shoals, Alabama. The artists that had brought Atlantic to prominence in the '50s were either supplanted or supplemented by a new generation of supremely gifted artists, including Solomon Burke, Percy Sledge, Wilson Pickett, Dusty Springfield (for her classic Dusty In Memphis album, although she recorded her vocals in New York) and, notably, Aretha Franklin. Like Ray Charles, Franklin had been miscast at another label (Columbia, where producer John Hammond had her singing pop-oriented material); and as he had done with Ray Charles, so he did with Aretha-leave her alone. In his autobiography, Rhythm And the Blues (in which he admitted that one of his many duties at Atlantic was to pay disc jockeys to play Atlantic records), Wexler says, "My idea was to make good tracks, use the best players, put Aretha back on piano and let the lady wail." To The Wall Street Journal's rock and pop music critic Jim Fusilli, Franklin explained the simple secret of Wexler's success with her over a span of 14 albums: "He provided the vehicle to allow me to perform and express myself."

As an example of the insight Wexler could bring to a session, consider that one of his most important contributions to one of the most famous of all soul recordings, Wilson Pickett's "In the Midnight Hour," came by way of his dancing feet. In an interview with Jann Wenner for Rolling Stone, the members of Booker T. and the MG's, who accompanied Pickett on the session, recalled how the artist had come in with a rhythmic idea, and from there guitarist Steve Cropper had started building the rest of the song.

Cropper told Wenner: "When I wrote the song I had it going a completely different way. Basically the changes were the same, basic feel was the same, but there's a different color about it. During the session Jerry said, 'Why don't you pick upon this thing here?' He said this was the way the kids were dancing, they were putting the accent on two. Basically we have been one beat accenters with an afterbeat, it was like 'boom dah,' but here this was a thing that 'un-chaw,' just the reverse as far as the accent goes. The back beat was somewhat delayed and it just put it in that rhythm, and Al [MG's drummer Al Jackson] and I have been using that as a natural thing now, ever since we did it. We play a downbeat and then two is just almost on but a little bit behind only with complete impact. It turned us on to a heck of a thing."

Jackson added, "It was different," and Cropper pointed out that the "Midnight Hour" session yielded four hit singles: "In the Midnight Hour," "Don't Fight It," "I'm Not Tired" and "It's a Man's Way." MG's bassist Donald "Duck" Dunn emphasized, "The bass thing was really Jerry Wexler's idea. Like Steve said, we had it going another way. Jerry came out and did the jerk dance."

Wenner asked for clarification: "Jerry came out of the booth and started dancing?"

Duck Dunn: "To the jerk."

Steve Cropper: "Yeah, he actually came out and said, 'Do it this way, this is the way they're doing it.'"

Wenner asked if Wexler's dance had made "that great a change of direction," and both Jackson and Cropper agreed it had, with Cropper observing: "I think it was the first time we had a chance to work with somebody that was up on the music scene from a different part of the country. We had been doing our own kind of thing, the way we wanted to do it."

Author Charles Gillett, in his definitive history of Atlantic Records, Making Tracks: Atlantic Records and the Growth of a Multi-Billion-Dollar Industry (1974, Dutton), noted, "The Stax sound really dates from that session." In Sweet Soul Music: Rhythm and Blues and the Southern Dream of Freedom (1986, Harper & Row), author Peter Guralnick charted the impact on the label's bottom line and the culture in general of Atlantic's foray into the south, along with Wexler's role in this ascension. "Between 1962 and 1967," Guralnick writes, "Atlantic increased sales by 500 percent, primarily on the basis of its ever-increasing share of the soul market; two-thirds of the label's singles were geared to black sales, 50 percent of its albums. By June of 1967 eighteen of the Top 100 soul songs were on the Atlantic label. Like Sun Records in rockabilly or Chess Records in postwar down-home blues, Atlantic truly dominated the world of southern soul, and Jerry Wexler was perceived in many quarters as the hip philanthropist responsible for it all. To Wexler, never reluctant to deliver a candid opinion (but whose candor will generally serve a useful purpose), Motown defied the laws of sociology, while Atlantic 'was interested in making music for black adults-that was our emphasis, that was the closest to what we liked. We didn't care about doo-wops, we didn't care about surfing, we didn't care about the Beatles-that was just not compatible with what we were into. We wanted to make records that were in tune and in time, rhythm and blues played without slop but nevertheless with a lot of strength and a lot of soul. I don't believe in being meretricious on purpose. Bad is bad, no matter what the intention is. Even in the beginning, when we didn't know how to make records, w went for a solid beat, good licks, and good intonation. Our records sounded good, they sold, and they're still around.'

In the '70s Wexler signed Willie Nelson to Atlantic, and Nelson's two albums for the label, Shotgun Willie and Phases and Stages, ignited one of the dominant careers of the past half-century. A near-lifelong atheist, he produced Bob Dylan's 1979 Slow Train Coming, a celebration of the artist's new (and short-lived) embrace of Christianity and was thanked, along with God, by Dylan in accepting a Grammy Award for Best Male Rock Vocal for the song "Gotta Serve Somebody." He also signed and produced Dire Straits' acclaimed debut album. In the next decade he encouraged Linda Ronstadt's interest in classic pop music, which resulted in a trio of heralded, career altering albums she made with legendary Frank Sinatra arranger Nelson Riddle. In a 1983 interview with The New York Times, Ronstadt said, "One thing Jerry Wexler taught me was that if you've got a sexy or torchy song, you mustn't attitudinize on top of it, because it sounds redundant."

A mercurial personality who could be abrasive and condescending one minute and generous and empathetic the next, Wexler was married three times and fathered three children. He is survived by his wife, Jean Arnold, a son, Paul, of High Bridge, NJ, and a daughter, Lisa Wexler of Kingston, NY. Another daughter, Anita, died of AIDS in 1989.

Tom Thurman, a filmmaker who directed a documentary about Wexler's life, Immaculate Funk, says when asked what he wanted written on his tombstone, Wexler had an immediate answer: "Two words: More Bass."

***

Hot Buttered Soul

Isaac Hayes

August 20, 1942-August 10, 2008

Rising from the rural poverty of the sharecropping family he was born into in Covington, TN, to pop culture superstardom on the strength of his musical artistry, his outsized personality and his entrepreneurial instincts, Isaac Hayes had made a lasting contribution to soul music years before he cut his celebrated second album, 1969's ambitious Hot Buttered Soul. After arriving at Stax only two years out of high school (he was nearly 20 years when he graduated) in early 1964, Hayes initially filled in for Booker T. Jones, then away at college, on keyboards for an Otis Redding session. Later that year he teamed with another aspiring Stax artist, David Porter, and began writing songs, the first of which, "Can't See You When I Want To," Porter himself recorded. But, as Peter Guralnick notes in Sweet Soul Music: Rhythm and Blues and the Southern Dream of Freedom, "it was when Jerry Wexler signed Sam and Dave that they finally got their chance." Sam and Dave's third Stax single, a Hayes-Porter number titled "You Don't Know Like I Know" (its title taken from the first line of the Violinaires' similarly propulsive gospel song, "What He Done For Me"), peaked at #7 on the R&B chart, and both Sam and Dave and Hayes and Porter were on a roll that would include 10 consecutive Top 20 R&B chart hits over the next three years; not all of those were Hayes/Porter tunes, but many of the landmarks were, including "Hold On (I'm Comin')," "When Something Is Wrong With My Baby," "I Thank You," "Wrap It Up" and the duo's (both duos) defining hit, 1967's "Soul Man," a chart-topping R&B single, #2 pop record and later voted in multiple polls as one of the top songs of the last half of the 20th Century.

In Sweet Soul Music Guralnick described a typical Hayes/Porter writing session: "In short order they had an office and a baby grand on whose surface every Stax artist would eventually carve his or her name and initials. Every song session would start ff with Ike and David (and maybe Sam and Dave, too) shooting craps on the green carpeting of their office. Or they might shoot a little miniature golf to loosen up before getting down to business. If Johnnie Taylor was coming in, they concentrated on a blues, for Carla Thomas it had to be 'something soft, for Sam and Dave it would be something coarse in attitude. We were always writing with the styling in mind, and the artist's personality,' says David Porter. 'We would try to make it like a tailored suit.'"

Following a period of soul searching after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Hayes emerged in 1969 as a solo artist with Hot Buttered Soul, a progressive soul album containing only four extended songs, including a 12-minute rumination on Bacharach-David's "Walk On By" and a 15-minute rendition of Jimmy Webb's "By The Time I Get to Phoenix." Edited into a double-sided single, the songs became Top 40 R&B and pop hits, and the album topped the R&B chart while remaining on the pop chart for 81 weeks. Thus began a run of seven #1 R&B albums over the next five years, and 20 charting albums (R&B and pop) over the next decade. An imposing physical specimen who appeared onstage bare-chested, shaven-headed, eyes hidden behind sunglasses and his neck and torso bedecked in gold chains, Hayes, who was a master of the seductive romantic soliloquy years ahead of Barry White, brought a new masculine style to the world of soul love men. Still, nothing cemented his name in the public consciousness more than the chunky, wah-wahed, lascivious, triple Grammy winning, Academy Award winning "Theme from 'Shaft,'" the album containing the song marking him as the first solo black artist to have a #1 R&B and pop album, and the first black composer to win an Oscar for Best Musical Score.

A prolific writer, Hayes never went long without releasing a new album, even as he gravitated to film and TV work as an actor and began producing other recording artists. None of this later work elevated his profile more than his voicing of the role of Chef in the animated Comedy Central satirical series South Park, concerning the adventures of a group of foul-mouthed grade school boys. His last dubiously great song, the Chef theme titled "Chocolate Salty Balls (P.S. I Love You)," was an international hit, topping the U.K. singles chart in 1999.

In 1995 Hayes joined the cult of Scientology and became one of its most prominent spokespeople. This led to his controversial departure from the show in March 2006, following an episode that mercilessly lampooned the cult and made repeated references to celebrity Scientologists Tom Cruise and John Travolta as "refusing to come out of the closet" (they had in fact locked themselves in a closet in the episode).

From his South Park departure to the end of his life, Hayes's life became the subject of speculation and rumor, much of it fueled by his own silence. The creators of South Park, Trey Parker and Matt Stone, say Hayes never uttered a word of complaint to them concerning the Scientology episode, although a statement was issued in Hayes's name saying, "There is a time when satire ends and intolerance and bigotry towards religious beliefs of others begins." Stone maintained that Hayes' complaints stemmed directly from the show's send-up of Scientology and noted that the artist "has no problem—and he's cashed plenty of checks—with our show making fun of Christians, Muslims, Mormons or Jews. [We] never heard a peep out of Isaac in any way until we did Scientology. He wants a different standard for religions other than his own, and to me, that is where intolerance and bigotry begin." Subsequently, Stone and Parker released Hayes from his contract as he had requested.

The loss of income is reported to have placed severe pressure on Hayes, who had fathered 11 children, and had 16 great grandchildren. He had lost the rights to all his hit songs in 1977, although his undetermined heirs will have those rights returned to them as the songs come up for copyright renewal. A friend of Hayes's, Fox News reporter and documentary filmmaker (Hayes appears in Friedman's Only the Strong Survive) Roger Friedman, has filed two extensive reports about the artist, questioning whether Hayes left South Park of his own volition or was forced out by the Scientology hierarchy, noting how Hayes was not allowed to speak for himself but rather through a Scientology spokesperson assigned to accompany him, much as Cruise's wife Katie Holmes is reported to have a Scientology buffer around her.

Attending a Hayes performance at B.B. King's club in New York City in January 2007, Friedman declared "the show was abomination. Isaac was plunked down at a keyboard, where he pretended to front his band. He spoke-sang, and his words were halting. He was not the Isaac Hayes of the past. "What was worse was that he barely knew me. He had appeared in my documentary, Only the Strong Survive, released in 2003. We knew each other very well. I was actually surprised that his Scientology minder, Christina Kumi Kimball, with whom I had difficult encounters in the past, let me see him backstage at BB King's. Our meeting was brief, and Isaac said quietly that he did know me. But the light was out in his eyes, and the situation was worrisome."

Friedman goes on to speculate that the financial demands the Scientologists make of their members were forcing Hayes back onto the stage in order to meet his commitments. He also wondered about the quality of care Hayes was receiving:

"But there are a lot of questions still to be raised about Isaac Hayes' death. Why, for example, was a stroke survivor on a treadmill by himself? What was his condition? What kind of treatment had he had since the stroke? Members of Scientology are required to sign a form promising they will never seek psychiatric or mental assistance. But stroke rehabilitation involves the help of neurologists and often psychiatrists, not to mention psychotropic drugs - exactly the kind Scientology proselytizes against."

Despite the sad final years of his life, Isaac Hayes left lasting monuments to his country and to the world, both in his music and by way of his own philanthropical work aimed at fighting illiteracy and poverty and promoting education through his Isaac Hayes Foundation. After visiting Africa with Barry White in 1991, he came back to America determined to build a school in Ghana, where he had been appointed King for Development and been given land on which to build a palace. In 1998 he returned to Ghana to participate in the groundbreaking ceremony for the school, an 8,000 square foot facility called NekoTech, which opened in 2000. According to the Isaac Hayes website, "Today, it not only delivers literacy, education, computer technology and Internet access, and health education, but also houses a chapter of the World Literacy Crusade. Johnson & Johnson, a major donor, also shipped 400 bicycles over, which are used for races around the school to promote HIV awareness to children and adults."

Roger Friedman's reports on Isaac Hayes can be found here:

http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,401321,00.html

http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,188463,00.html

***

Etched In Steel

Don Helms

February 28, 1927-August 11, 2008

Don Helms, the last surviving member of Hank Williams' Drifting Cowboys, died August 11 in Nashville from complications of heart surgery and diabetes. A steel guitarist, Helms's is the distinctive sound heard on more than 100 Williams songs and on 10 of his 11 #1 country hits. Following Williams's death in 1953, the New Brockton, AL-born Helms was in demand as a session player, and racked up credits including Lefty Frizzell's "Long Black Veil," Loretta Lynn's "Blue Kentucky Girl," Patsy Cline's "Walking After Midnight," the Louvin Brothers' "Cash On the Barrelhead," Stonewall Jackson's "Waterloo," and accompanied Johnny Cash on several of the Man in Black's early Columbia recordings. He also recorded with Webb Pierce, Jim Reeves and Ferlin Husky, among others (including, improbably, Jon Bon Jovi), up to the present day.

"After the great tunes and Hank's mournful voice, the next thing you think about in those songs is the steel guitar," Bill Lloyd, the curator of stringed instruments at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, told The New York Times. "It is the quintessential honky-tonk steel sound - tuneful, aggressive, full of attitude."

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024