Classical Perspectives

‘Living Presence’ Lives Again

New 51-CD box set collects many of the legendary series’ most enduring performances and underscores anew the artistry and inventiveness of producer Wilma Cozart Fine

In what is a major event for audiophiles and classical music lovers, Decca Classics has released Mercury Living Presence: The Collectors Edition, a 51-CD box set of recordings originally issued by Mercury Records in its Living Presence series. Containing 50 CDs (all remastered in the 1990s by the legendary producer Wilma Cozart Fine) plus a bonus CD interview with Mrs. Fine and deluxe booklet detailing the history of Mercury Living Presence. Mercury Living Presence is unique in many ways--an American company, from the heyday of classical recording in the U.S., that produced some of the most sonically realistic recordings at the dawn of the stereo era. Precious few stereo LPs were pressed when these recordings were issued, and they became some of the rarest, most collectible classical discs ever. Mercury Living Presence continues to enjoy a special reputation as one of the most enterprising, prestigious and sonically-spectacular labels in the history of classical recording.

Some of these recording have been available on CD and on SACD. However, many are now deleted and only available second-hand or through auction sellers at premium prices. This box set affords collectors an opportunity to acquire 50 classic recordings at an irresistible price--$100.11--in a package that may well become collectible itself. The set features such celebrated artists as Antal Dorati, Rafael Kubelik, Gina Bachauer, Byron Janis, Janos Starker, and Henryk Szeryng. Titles include the famous Pictures At An Exhibition (Moussorgsky); Aaron Copland’s Appalachian Spring, Billy the Kid, Danzon Cubano and Al Salon Mexico; Parts 1 and 2 of Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker and of course the towering production of the 1812 Oveture.

The Great Northern Hotel, home of Fine Recordings Inc. as it appeared in the 1950s. The studio began operation in 1957, initially doing disk mastering; the hotel’s former Ballroom was transformed into a recording studio. (Photo: T. Fine)Key to the Living Presence sonic quality was, first, the mic placement in the studios of Fine Recording Inc. A production complex located in the Great Northern Hotel on 57th and Madison in New York City, the facility eventually encompassed four studios, extensive disk mastering operations and synthesizer pioneer Walter Sear's Moog laboratory. In 1951, under the direction of recording engineer C. Robert (Bob) Fine and recording director David Hall, Mercury Records initiated a recording technique using a single microphone to record symphony orchestras. Fine had for several years used a single microphone for various Mercury small-ensemble classical recordings produced by John Hammond and later Mitch Miller (indeed, Miller, using his full name of Mitchell Miller, made several recordings as a featured oboe player for Mercury in the late '40s). The first record in this new Mercury Olympian Series was Pictures at an Exhibition performed by Rafael Kubelík and the Chicago Symphony. The Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra became famous using this technique. Under the leadership of conductor Antal Doráti, the Orchestra made a series of classical albums that were well reviewed and sold briskly, including the first-ever complete recordings of Tchaikovsky's ballets Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty and The Nutcracker. Dorati's 1954 one-mic monaural recording (Mercury MG 50054) and 1958 three-mic stereo rerecording (Mercury MG 50054) of Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture included dramatic overdub recordings of 1812-era artillery and the giant bell tower at Yale University. Besides Mercury's mono and stereo versions of the 1812, only one other classical album rang up gold record sales in the 1950s in the U.S. The recording of the 1812 Overture is considered by many to be one of the best performances of that work and is still in reissue in 2011, nearly 60 years after its first release.

The ballroom of the Great Northern Hotel as it looked in 1900. It was later transformed into a recording studio in the Fine Recording complex. The Tiffany glass ceiling remained in place. (Photo: T. Fine)New York Times music critic Howard Taubman described the Mercury sound on Pictures at an Exhibition as "being in the living presence of the orchestra" and Mercury eventually began releasing its classical recordings under the “Living Presence” series' name. The recordings were produced by Mercury vice president Wilma Cozart, who later married Bob Fine. Cozart took over recording director duties in 1953 and in the 1990s also produced the CD reissues of more than half of the Mercury Living Presence catalog. By the late '50s, the Mercury Living Presence crew included session musical supervisors Harold Lawrence and Clair van Ausdall and associate engineer Robert Eberenz. When Cozart retired in 1964, Lawrence took over the Mercury classical division and continued producing Mercury Living Presence records into 1967.

Besides the recordings with the Chicago and Minneapolis orchestras, Mercury also recorded Howard Hanson with the Eastman Rochester Orchestra, Frederick Fennell with the Eastman Wind Ensemble, and Paul Paray with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. Dorati made some recordings in the United Kingdom with the London Symphony Orchestra for Mercury during the 1960s.

Promotional video for Mercury Living Presence: The Collectors EditionIn late 1955, Mercury began using three omni-directional microphones to make stereo recordings on three-track tape. The technique was an expansion on the mono process--center was still paramount. Once the center, single microphone was set, the sides were set to provide the depth and width heard in the stereo recordings. The center mike still fed the mono LP releases, which accompanied stereo LPs into the 1960s. In 1961 Mercury enhanced the three-microphone stereo technique by using 35 mm magnetic film instead of half-inch tape for recording. The greater emulsion thickness, track width and speed (90 feet per min or 18 ips) of 35 mm magnetic film increased prevention of tape layer print-through and pre-echo and gained in addition extended frequency range and transient response. The Mercury “Living Presence” stereo records were mastered directly from the three-track tapes or films, with a 3-2 mix occurring in the mastering room. The same technique--and restored vintage equipment of the same type--was used for the CD reissues. No digital enhancement or noise reduction was used.

Bedrich Smetana, Ma Vlast (The Moldau), Chicago Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Rafael Kubelik, released 1952, Mercury Living Presence SeriesReviewing the first set of Mrs. Fine’s CD reissues of her original work in the September 30, 1990, issue of the New York Times, Stereo Review contributing editor Richard Freed noted that the special status of the Living Presence series among audiophiles “was built on a strong mix of imaginative repertory, authoritative performances and a dramatically straightforward approach in recording them that insured a vividness that would not fade with time. Over the years, as LPs disappeared or were reissued in sound-altered editions, the original pressings acquired legendary status, and collectors offered up to $300 for certain items. Now, even those who believe that no CD or digital processing can match the finest all-analog LP may find ‘Living Presence’ restored in all its former glory and perhaps a bit more on the new Mercury CDs.”

***

‘The Keeper of the Flame at Mercury’

Grammys honor the art and vision of Wilma Cozart Fine

C. Robert Fine and Wilma Cozart Fine working at the Bayside Westrex Console in Fine RecordingOn February 1, 2011, Harry Pearson, founding editor of The Absolute Sound, announced the recipients of the Grammy Awards’ Special Merit Award winners for 2011. Among the honorees: Wilma Cozart Fine, the pioneering female producer behind Mercury’s acclaimed Living Presence Series.

Pearson’s statement as published at Grammy.com:

The words Wilma Cozart Fine lived by were "trust your ears." This was the guiding principle that defined her working life. For those who don't know the name, hers was a working life to remember.

Cozart Fine, who died at age 82 in September 2009, was the recording director for Mercury Records' Living Presence classical recordings during the mid-'50s and '60s. And yet, the recordings she produced, though more than 50 years old, even by contemporary standards, sound as fresh on the original LPs and remasterings on CD (she supervised the latter) as any two-channel CDs being issued today.

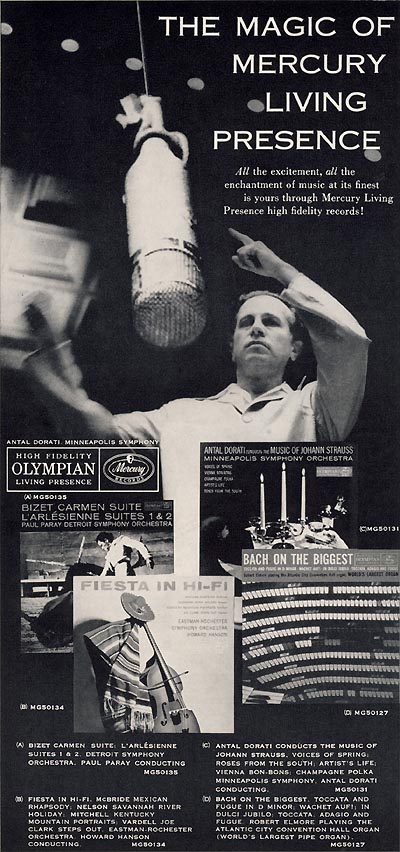

An early newspaper advertisement for the Mercury Living Presence SeriesCozart Fine was a creature of seeming contradictions. She was a pragmatic, hardheaded visionary, the sharpness of whose business and artistic judgments were matched by the acuity of her hearing. She had an exact memory of the sound of the music she heard and used that as a reference with which to assess any reproductions of it.

She started working for Mercury when it was largely a pop label, taking over its quite small classical division. She built it into a force to be reckoned with, imitated by all the major American labels of the time, even RCA Victor. She signed Antal Dorati (whom she had worked for with the Minneapolis and Dallas Symphony Orchestras, the latter of which she served as his personal secretary and later as de facto manager), Janos Starker, Byron Janis, Paul Paray, Frederick Fennell And The Eastman Wind Ensemble, and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, among others. She oversaw the first American recordings made in Cold War Russia, and developed marketing innovations still copied to this day.

Cozart Fine became the keeper of the flame at Mercury, working tirelessly and with an uncompromising will ("the iron fist inside the velvet glove" is a phrase used by more than one associate who worked with her) to preserve the sound of the Living Presence Recordings, which, essentially, she oversaw (with eagle ears), while her husband, C. Robert Fine, provided the engineering know-how to create a simulacrum, which was, at heart, as closely faithful to the original as the technology allowed. All of this was done with minimal miking and jiggling with the signal.

Because of her musical training, both in college and afterward (in Dallas and Minneapolis with Dorati), she subscribed, undeviatingly, to the concept of music itself, the absolute sound, unamplified music occurring in a real space, as her final reference. As a result, virtually every one of the Living Presence issues is a prime example of the recorded art. They were then, still are now, and will continue to be touchstones into the future.

***

Wilma Cozart Fine at the Western Electric mixin console‘I Do Love Music With All My Heart’

Remembering Wilma Cozart Fine

Born in Aberdeen, MS, and raised in Fort Worth, TX, Wilma Cozart Fine attended North Texas State University, where she studied music education and business administration, and took a job as personal secretary to Antal Dorati when he was conductor of the Dallas Symphony. When Dorati was hired by the Minneapolis Symphony, she followed him, but soon after decided to move to New York. With a recommendation from Dorati, she was hired by Mercury in 195o and promoted to vice president 1954. Working with (and eventually marrying) C. Robert Fine, who had a reputation as an innovative engineer, she helped develop recording techniques that were striking and unusual in their sonic presence, aiming to recreate in the listening environment the experience of the concert hall. One of their most spectacular and enduring productions remains 1954's recording of Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture, with Antal Dorati and the Minneapolis Symphony, that was realized as an aural extravaganza complete with thunderous blasts from West Point's historic cannons and the tolling of giant bells as recorded in Yale University's bell tower. The Fines recorded the symphony with one microphone, a technique Bob Fine had used for years with small classical combos but never before with a symphonic orchestra. The 1812 Overture album went Gold, one of only two classical albums in the decade to attain such certification.

Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture as recorded for the Mercury Living Presence Series, produced by Wilma Cozart Fine, engineered by C. Robert Fine. West Point's historic cannons provided the thunderous blasts Tchaikovsky's score called for, and the tolling bells were recorded at Yale University's bell tower.Later, when recording in stereo to 3-track tape, Mrs. Fine employed three omnidirectional microphones, to great sonic advantage. As she explained in a 1995 interview with award winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie (now posted online), "With the Mercury records, you always hear the center, but it isn't really there. It has been combined into the left and the right, and done in such a way that the illusion is complete all the way across the stage. In other words you don't have a hole there. You have the winds sitting back where they would when the orchestra was in its normal seating on the stage. I try to recreate exactly what that microphone picked up at the time of the session. Sometimes it's not always the same and also the acoustics of the hall determines how this works to a great extent. How close the mics are to each other is greatly influenced by the acoustics in the hall, so it's certainly not an arbitrary thing." In 1961, the Fines enhanced the three-mic stereo approach by using 35mm magnetic film in place of half-inch tape during recording, which effectively knocked out sound leaks and echoes while adding greater frequency range and transient response. The Fines also mixed all channels of the recordings directly to a cutting lathe rather than to tape, thus eliminating extra hiss.

With the launch of the "Living Presence" classical series, Mrs. Fine took over recording director duties and continued in that position until her retirement in 1964. She came out of retirement in 1989 to oversee the transfer of the Living Presence series to CD, which gave her an opportunity to weigh in on the ongoing debate over digital versus analog sound. To Duffie she dismissed the entire argument as "false in concept," asserting that the two cannot be compared.

Wilma Cozart Fine at the Western Electric mixing console in the early '90s , surrounded by a host of components as she poses on the occasion of the release of another batch of CDs containing transfers of legendary Mercury Living Presence tapes."The argument that CDs are better than LPs is not the question in my opinion," she said. "The crux of the matter is, again, the original recording, because if you're trying to judge a technology by the time it gets in the home, a lot of things could have affected it. If you said that you don't think a CD is as good as an LP but you didn't relate that to specific repertoire you could say that, or you could say a CD is better, but even then it's not really valid. They aren't played through the same chain, they're not played through the same system. I do think that analog recording is the best thing there is; there's no question about that in my mind. I think it's absolutely wonderful, but I don't think that it's better when it gets to you in the home, because a lot of things happen, including what you're playing it on at the time. The fact is that you are going to have some surface things, probably, when you play a record. If they didn't happen before you opened the record, they will happen by the second time you play it or probably before you get through it the first time. One of the reasons I feel that Mercury CDs have the quality and the sound which they do is that they come from an analog source. The second thing is they are made for CDs as far as they can go through the change from tube equipment. No transistors. Those are two of the distinguishing influences with the sound and I'm very happy that they do come from analog originals."

Asked by Duffie if she was pleased with her career, she answered enthusiastically. "Oh yes, I've had a wonderful time. I'm so fortunate to have been able to work with these wonderful artists over the years and know them, and to get to know first hand as much music as I do. You do learn it whenever you record it because you have to take it apart and put it back together from so many vantage points. I do love music with all my heart and wanted to work with it since I was a child. I consider myself really so fortunate to have had the privilege of doing that. I enjoy it just as much now as I did when I first started."

Beethoven, Symphony no. 5 in C minor op 67, first movement; London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Antal Dorati; a Mercury Living Presence release, 1962

New & Noteworthy in Classical Music

the varieties of experience in cinema music

CLASSICAL HITS OF THE CINEMA

Various artists

EMIAs a rule, classical music in films is used as a shorthand: Handel or Vivaldi indicates that the stuffed shirts have arrived, Beethoven's "Ode to Joy" announces that Armageddon may be just around the corner and Wagner is a safe bet that trouble is brewing. Anytime an aria by Verdi or Puccini is heard, it's likely someone will be stabbed, raped, murdered or obsessively stalked.

Now a five-CD box set, Classical Hits of the Cinema, reminds us that classical music has long been intrinsic in helping filmmakers tell stories, create characters and add atmosphere. And most tellingly, the art form is not simply used to exude class, luxury or sophistication.

Tchaikovsky’s ‘Dance of the Little Swans’ from Swan Lake, was used in The Black Swan and is featured on Classical Hits of the CinemaAmong the set's highlights: We're invited to remember how the cannibalistic killer Hannibal Lecter (played by Anthony Hopkins) pursued his grisly work amid the measured piano notes of the 25th of Bach's Goldberg Variations. Or recall how the hooligans in Stanley Kubrick's 1971 A Clockwork Orange pursued their agenda of ultra-violence to the strains of Beethoven's "Ode to Joy." And there's 1979's Apocalypse Now, where the "Ride of the Valkyries" is played over American helicopter-mounted loudspeakers during their assault on a Vietnamese village.

Love Theme from The Godfather appears on Classical Hits of the CinemaNumerous scenes use classical music to set the stage for heroism and epic sentiments. There's Philadelphia, the 1993 drama about AIDS, with its prominent use of "La mamma morta," the rapturous aria from Andrea Chenier. More recently, Of Gods and Men, the 2010 French tale of Christian monks peacefully coexisting in Algeria until the arrival of fundamentalists, has a pivotal scene marked by the second movement of Beethoven's Seventh Symphony (right). And The Pianist (2002), the story of a Polish Jewish musician who struggles to survive the destruction of the Warsaw ghetto of World War II, is made personal through Chopin's Nocturne No. 20 and Ballade No. 1.

From The Piano, Michael Nyman performs his suite of ‘The Promise/The Heart Asks Pleasure First.’ Included on Classical Hits of the Cinema.The set features classical highlights from a mix of independent and blockbuster films, plus a full CD of cues by actual film-score composers, from Enio Morricone to Howard Shore. It should be noted that most of these performances were not drawn from the original soundtrack albums to these films, but the connections are clear and numerous nonetheless.

Album of the Week, WQXR-AM, February 19, 2012***

‘…real, involved and borne by a living spirit’

JOHN RAMSAY: STRING QUARTETS 1-4

Fitzwilliam String Quartet

Métier (released February 2012String Quartet No. 1 in D minor; String Quartet No. 2 in E minor ("Shackleton"); String Quartet No. 3 in C major; String Quartet No. 4 ("Charles Darwin").

Some composers write chamber music based on the fact that it will be played by a string quartet, pre-determined to a certain extent by that ensemble's character and disposition. Others, like John Ramsay (b 1931), compose music to be performed by a string quartet. You may be thinking: Well, isn't that exactly the same thing? It may seem that way on the surface, but to me these two approaches to composition are worlds apart. The first always sounds fabricated, shackled and unimaginative. The second technique on the other hand, like the music of John Ramsay, sounds real, involved and borne by a living spirit.

All four quartets were written over a short period between 2001 and 2009, and all display a strong grasp of the idiom, with neo-romanticism and a solid tonal structure as their points of origin. The String Quartet No. 4 ("Charles Darwin") in particular, has captured my unswerving attention. It was written to commemorate the 200th anniversary of Darwin's birth, and dedicated to the Fitzwilliam String Quartet. It is laid out over 21 minutes as one continuous movement, depicting the evolution of the Earth, leading to the arrival of the human race and its destructive legacy, and ending with speculation as to the future of life on this planet. The opening Adagio, with its barely audible whispers, and plaintive and haunting four-note motif, sets life on its evolutionary path, leading inexorably to man's influence set to music as a War fugue, leaving the planet scorched and desolate. The quartet quietly ends with an Epilogue that seems to point to a glimmer of hope presented by the possibilities of future life on this barren planet. Strong subject matter to set to music for four instruments, but this is exactly the type of music making that supports my opening paragraph.

These masterful quartets are given here their world première recording by the distinguished Fitzwilliam String Quartet, who hold the honor of having performed the Western premières of the last three quartets of Dmitri Shostakovich, and of being the first ensemble to record all fifteen of the Shostakovich quartets for Decca--recordings that are still on the market today and still viewed by many as the standard to match. And maybe 40 years from now, these new recordings of the John Ramsay quartets will have acquired the same stature and respect.

Jean-Yves Duperron--February 2

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024