A Charles Dickens Bicentennial Moment

Charles Dickens and Music

By James T. Lightwood

Author of

Hymn-Tunes and their StoryLondon

CHARLES H. KELLY

25-35 CITY ROAD, AND 26 PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C.

First Edition, 1912IN PLEASANT MEMORY

OF MANY HAPPY YEARS

AT PEMBROKE HOUSE, LYTHAM

PREFACE

For many years I have been interested in the various musical references in Dickens' works, and have had the impression that a careful examination of his writings would reveal an aspect of his character hitherto unknown, and, I may add, unsuspected. The centenary of his birth hastened a work long contemplated, and a first reading (after many years) brought to light an amount of material far in excess of what I anticipated, while a second examination convinced me that there is, perhaps, no great writer who has made a more extensive use of music to illustrate character and create incident than Charles Dickens. From an historical point of view these references are of the utmost importance, for they reflect to a nicety the general condition of ordinary musical life in England during the middle of the last century. We do not, of course, look to Dickens for a history of classical music during the period--those who want this will find it in the newspapers and magazines; but for the story of music in the ordinary English home, for the popular songs of the period, for the average musical attainments of the middle and lower classes (music was not the correct thing amongst the 'upper ten'), we must turn to the pages of Dickens' novels. It is certainly strange that no one has hitherto thought of tapping this source of information. In and about 1887 the papers teemed with articles that outlined the history of music during the first fifty years of Victoria's reign; but I have not seen one that attempted to derive first-hand information from the sources referred to, nor indeed does the subject of 'Dickens and Music' ever appear to have received the attention which, in my opinion, it deserves.

I do not profess to have chronicled all the musical references, nor has it been possible to identify every one of the numerous quotations from songs, although I have consulted such excellent authorities as Dr. Cummings, Mr. Worden (Preston), and Mr. J. Allanson Benson (Bromley). I have to thank Mr. Frank Kidson, who, I understand, had already planned a work of this description, for his kind advice and assistance. There is no living writer who has such a wonderful knowledge of old songs as Mr. Kidson, a knowledge which he is ever ready to put at the disposal of others. Even now there are some half-dozen songs which every attempt to run to earth has failed, though I have tried to 'mole 'em out' (as Mr. Pancks would say) by searching through some hundreds of song-books and some thousands of separate songs.

Should any of my readers be able to throw light on dark places I shall be very glad to hear from them, with a view to making the information here presented as complete and correct as possible if another edition should be called for. May I suggest to the Secretaries of our Literary Societies, Guilds, and similar organizations that a pleasant evening might be spent in rendering some of the music referred to by Dickens. The proceedings might be varied by readings from his works or by historical notes on the music. Many of the pieces are still in print, and I shall be glad to render assistance in tracing them. Perhaps this idea will also commend itself to the members of the Dickens Fellowship, an organization with which all lovers of the great novelist ought to associate themselves.

JAMES T. LIGHTWOOD.

Lytham,

October, 1912.I truly love Dickens; and discern in the inner man of him a tone of real Music which struggles to express itself, as it may in these bewildered, stupefied and, indeed, very crusty and distracted days--better or worse!

Thomas Carlyle.Chapter 1: Dickens As a Musician

The attempts to instill the elements of music into Charles Dickens when he was a small boy do not appear to have been attended with success. Mr. Kitton tells us that he learnt the piano during his school days, but his master gave him up in despair. Mr. Bowden, an old schoolfellow of the novelist's when he was at Wellington House Academy, in Hampstead Road, says that music used to be taught there, and that Dickens received lessons on the violin, but he made no progress, and soon relinquished it. It was not until many years after that he made his third and last attempt to become an instrumentalist. During his first transatlantic voyage he wrote to Forster telling him that he had bought an accordion.

The steward lent me one on the passage out, and I regaled the ladies' cabin with my performances. You can't think with what feelings I play 'Home, Sweet Home' every night, or how pleasantly sad it makes us.

On the voyage back he gives the following description of the musical talents of his fellow passengers:

One played the accordion, another the violin, and another (who usually began at six o'clock a.m.) the key bugle: the combined effect of which instruments, when they all played different tunes, in different parts of the ship, at the same time, and within hearing of each other, as they sometimes did (everybody being intensely satisfied with his own performance), was sublimely hideous.

He does not tell us whether he was one of the performers on these occasions.

But although he failed as an instrumentalist he took delight in hearing music, and was always an appreciative yet critical listener to what was good and tuneful. His favourite composers were Mendelssohn--whose Lieder he was specially fond of(1)--Chopin, and Mozart. He heard Gounod's Faust whilst he was in Paris, and confesses to having been quite overcome with the beauty of the music. 'I couldn't bear it,' he says, in one of his letters, 'and gave in completely. The composer must be a very remarkable man indeed.' At the same time he became acquainted with Offenbach's music, and heard Orphée aux enfers. This was in February, 1863. Here also he made the acquaintance of Auber, 'a stolid little elderly man, rather petulant in manner.' He told Dickens that he had lived for a time at 'Stock Noonton' (Stoke Newington) in order to study English, but he had forgotten it all. In the description of a dinner in the Sketches we read that

The knives and forks form a pleasing accompaniment to Auber's music, and Auber's music would form a pleasing accompaniment to the dinner, if you could hear anything besides the cymbals.

He met Meyerbeer on one occasion at Lord John Russell's. The musician congratulated him on his outspoken language on Sunday observance, a subject in which Dickens was deeply interested, and on which he advocated his views at length in the papers entitled Sunday under Three Heads.

From Gounod’s Faust, Walton Gronrgoos sings Valentin’s aria, ‘Avant de quitter ces lieux.’ Wiener Staatsoper (Vienna State Opera), orchestra and chorus, conducted by Erich Binder, 1985 production. Upon hearing Faust, Dickens wrote: ‘I couldn’t bear it and gave in completely. The composer must be a very remarkable man indeed.’Dickens was acquainted with Jenny Lind, and he gives the following amusing story in a letter to Douglas Jerrold, dated Paris, February 14, 1847:

I am somehow reminded of a good story I heard the other night from a man who was a witness of it and an actor in it. At a certain German town last autumn there was a tremendous furore about Jenny Lind, who, after driving the whole place mad, left it, on her travels, early one morning. The moment her carriage was outside the gates, a party of rampant students who had escorted it rushed back to the inn, demanded to be shown to her bedroom, swept like a whirlwind upstairs into the room indicated to them, tore up the sheets, and wore them in strips as decorations. An hour or two afterwards a bald old gentleman of amiable appearance, an Englishman, who was staying in the hotel, came to breakfast at the table d'hôte, and was observed to be much disturbed in his mind, and to show great terror whenever a student came near him. At last he said, in a low voice, to some people who were near him at the table, 'You are English gentlemen, I observe. Most extraordinary people, these Germans. Students, as a body, raving mad, gentlemen!' 'Oh, no,' said somebody else: 'excitable, but very good fellows, and very sensible.' 'By God, sir!' returned the old gentleman, still more disturbed, 'then there's something political in it, and I'm a marked man. I went out for a little walk this morning after shaving, and while I was gone'--he fell into a terrible perspiration as he told it--'they burst into my bedroom, tore up my sheets, and are now patrolling the town in all directions with bits of 'em in their button-holes.' I needn't wind up by adding that they had gone to the wrong chamber.

Dickens was acquainted with Jenny Lind, ‘The Swedish Nightingale,’ one of the 19th Century’s most beloved (except by critics) singers. In a letter to a friend in 1847, Dickens described how Ms. Lind’s performance ‘at a certain German town’ had incited a group of students to riot inside the hotel where the singer was staying. In 1850 Lind was invited to tour America by showman P.T. Barnum. From these concerts she earned more than $350,000, most of which she donated to various charities, but also used a portion of to endow free schools in Sweden. Upon her death in 1887 she bequeathed a large portion of her great wealth to provide for the education of poor Protestant students in Sweden. In this scene from the 1934 film The Mighty Barnum (directed by Walter Lang, with script by Gene Fowler), Virginia Bruce, portraying Jenny Lind (whose voice was never recorded), sings ‘Believe Me If All Those Endearing Young Charms,’ with Thomas Moore’s lyrics set to an old Irish air. Barnum is played by Wallace Beery, and his friend Bailey Walsh by Adolphe Menjou. In a 1930 film, the Sidney Franklin-directed A Lady’s Morals, Beery also portrayed Barnum, with Grace Moore in the Jenny Lind role.It was Dickens' habit wherever he went on his Continental travels to avail himself of any opportunity of visiting the opera; and his criticisms, though brief, are always to the point. He tells us this interesting fact about Carrara:

There is a beautiful little theatre there, built of marble, and they had it illuminated that night in my honour. There was really a very fair opera, but it is curious that the chorus has been always, time out of mind, made up of labourers in the quarries, who don't know a note of music, and sing entirely by ear.

But much as he loved music, Dickens could never bear the least sound or noise while he was studying or writing, and he ever waged a fierce war against church bells and itinerant musicians. Even when in Scotland his troubles did not cease, for he writes about 'a most infernal piper practising under the window for a competition of pipers which is to come off shortly.' Elsewhere he says that he found Dover 'too bandy' for him (he carefully explains he does not refer to its legs), while in a letter to Forster he complains bitterly of the vagrant musicians at Broadstairs, where he 'cannot write half an hour without the most excruciating organs, fiddles, bells, or glee singers.' The barrel-organ, which he somewhere calls an 'Italian box of music,' was one source of annoyance, but bells were his special aversion. 'If you know anybody at St. Paul's,' he wrote to Forster, 'I wish you'd send round and ask them not to ring the bell so. I can hardly hear my own ideas as they come into my head, and say what they mean.' His bell experiences at Genoa are referred to elsewhere.

How marvelously observant he was is manifest in the numerous references in his letters and works to the music he heard in the streets and squares of London and other places. Here is a description of Golden Square, London, W. (N.N.):

Two or three violins and a wind instrument from the Opera band reside within its precincts. Its boarding-houses are musical, and the notes of pianos and harps float in the evening time round the head of the mournful statue, the guardian genius of the little wilderness of shrubs, in the centre of the square.... Sounds of gruff voices practising vocal music invade the evening's silence, and the fumes of choice tobacco scent the air. There, snuff and cigars and German pipes and flutes, and violins and violoncellos, divide the supremacy between them. It is the region of song and smoke. Street bands are on their mettle in Golden Square, and itinerant glee singers quaver involuntarily as they raise their voices within its boundaries.

We have another picture in the description of Dombey's house, [note: in Dombey and Son, Dickens’s novel published in serial form between October 1846 and April 1848, and in hard cover in 1848] where--

the summer sun was never on the street but in the morning, about breakfast-time.... It was soon gone again, to return no more that day, and the bands of music and the straggling Punch's shows going after it left it a prey to the most dismal of organs and white mice.

AS A SINGER

Most of the writers about Dickens, and especially his personal friends, bear testimony both to his vocal power and his love of songs and singing. As a small boy we read of him and his sister Fanny standing on a table singing songs, and acting them as they sang. One of his favourite recitations was Dr. Watts' 'The voice of the sluggard,' which he used to give with great effect. The memory of these words lingered long in his mind, and both Captain Cuttle and Mr. Pecksniff quote them with excellent appropriateness.

When he grew up he retained his love of vocal music, and showed a strong predilection for national airs and old songs. Moore's Irish Melodies had also a special attraction for him. In the early days of his readings his voice frequently used to fail him, and Mr. Kitton tells us that in trying to recover the lost power he would test it by singing these melodies to himself as he walked about. It is not surprising, therefore, to find numerous references to these songs, as well as to other works by Moore, in his writings.

‘When Dickens grew up he retained his love of vocal music, and showed a strong predilection for national airs and old songs. Moore's Irish Melodies had also a special attraction for him.’: in this clip from the 1939 Henry Koster-directed movie Three Smart Girls Grow Up, 17-year-old Deanna Durbin performs a selection from Thomas Moore’s Irish Melodies, ‘The Last Rose of Summer,’ with Moore’s lyrics set to music by John Stevenson. Many of Moore’s songs are cited in the works of James Joyrce (including ‘The Last Rose of Summer’), and he is regarded as Ireland’s National Bard.From a humorous account of a concert on board ship we gather that Dickens possessed a tenor voice. Writing to his daughter from Boston in 1867, he says:

We had speech-making and singing in the saloon of the Cuba after the last dinner of the voyage. I think I have acquired a higher reputation from drawing out the captain, and getting him to take the second in 'All's Well' and likewise in 'There's not in the wide world' (3) (your parent taking the first), than from anything previously known of me on these shores.... We also sang (with a Chicago lady, and a strong-minded woman from I don't know where) 'Auld Lang Syne,' with a tender melancholy expressive of having all four been united from our cradles. The more dismal we were, the more delighted the company were. Once (when we paddled i' the burn) the captain took a little cruise round the compass on his own account, touching at the Canadian Boat Song, 3 and taking in supplies at Jubilate, 'Seas between us braid ha' roared,' and roared like ourselves.

J.T. Field, in his Yesterdays with Authors, says: 'To hear him sing an old-time stage song, such as he used to enjoy in his youth at a cheap London theatre ... was to become acquainted with one of the most delightful and original companions in the world.'

When at home he was fond of having music in the evening. His daughter tells us that on one occasion a member of his family was singing a song while he was apparently deep in his book, when he suddenly got up and saying 'You don't make enough of that word,' he sat down by the piano and showed how it should be sung.

On another occasion his criticism was more pointed.

One night a gentleman visitor insisted on singing 'By the sad sea waves,' which he did vilely, and he wound up his performance by a most unexpected and misplaced embellishment, or 'turn.' Dickens found the whole ordeal very trying, but managed to preserve a decorous silence till this sound fell on his ear, when his neighbour said to him, 'Whatever did he mean by that extraneous effort of melody?' 'Oh,' said Dickens, 'that's quite in accordance with rule. When things are at their worst they always take a turn.'

Forster relates that while he was at work on the Old Curiosity Shop he used to discover specimens of old ballads in his country walks between Broadstairs and Ramsgate, which so aroused his interest that when he returned to town towards the end of 1840 he thoroughly explored the ballad literature of Seven Dials(4), and would occasionally sing not a few of these wonderful discoveries with an effect that justified his reputation for comic singing in his childhood. We get a glimpse of his investigations in Out of the Season, where he tells us about that 'wonderful mystery, the music-shop,' with its assortment of polkas with coloured frontispieces, and also the book-shop, with its 'Little Warblers and Fairburn's Comic Songsters.'

Here too were ballads on the old ballad paper and in the old confusion of types, with an old man in a cocked hat, and an armchair, for the illustration to Will Watch the bold smuggler, and the Friar of Orders Grey, represented by a little girl in a hoop, with a ship in the distance. All these as of yore, when they were infinite delights to me.

On one of his explorations he met a landsman who told him about the running down of an emigrant ship, and how he heard a sound coming over the sea 'like a great sorrowful flute or Aeolian harp.' He makes another and very humorous reference to this instrument in a letter to Landor, in which he calls to mind

that steady snore of yours, which I once heard piercing the door of your bedroom ... reverberating along the bell-wire in the hall, so getting outside into the street, playing Aeolian harps among the area railings, and going down the New Road like the blast of a trumpet.

The deserted watering-place referred to in Out of the Season is Broadstairs, and he gives us a further insight into its musical resources in a letter to Miss Power written on July 2, 1847, in which he says that

a little tinkling box of music that stops at 'come' in the melody of the Buffalo Gals, and can't play 'out to-night,' and a white mouse, are the only amusements left at Broadstairs.

'Buffalo Gals' was a very popular song 'Sung with great applause by the Original Female American Serenaders.' (c. 1845.) The first verse will explain the above allusion:

As I went lum'rin' down de street, down de street,

A 'ansom gal I chanc'd to meet, oh, she was fair to view.

Buffalo gals, can't ye come out to-night, come out to-night, come out to-night;

Buffalo gals, can't ye come out to-night, and dance by the light of the moon.

Bruce Springsteen and the Seeger Sessions band, ‘Buffalo Gals,’ live at the Saratoga, NY, Performing Arts Center, June 19, 2006We find some interesting musical references and memories in the novelist's letters. Writing to Wilkie Collins in reference to his proposed sea voyage, he quotes Campbell's lines from 'Ye Mariners of England':

As I sweep

Through the deep

When the stormy winds do blow.There are other references to this song in the novels. I have pointed out elsewhere that the last line also belongs to a seventeenth-century song.

Writing to Mark Lemon (June, 1849) he gives an amusing parody of

Lesbia hath a beaming eye,

Beginning

Lemon is a little hipped.

In a letter to Maclise he says:

My foot is in the house,

My bath is on the sea,

And before I take a souse,

Here's a single note to thee.These lines are a reminiscence of Byron's ode to Thomas Moore, written from Venice on July 10, 1817:

My boat is on the shore,

And my bark is on the sea,

But before I go, Tom Moore,

Here's a double health to thee!

The words were set to music by Bishop. This first verse had a special attraction for Dickens, and he gives us two or three variations of it, including a very apt one from Dick Swiveller.Henry F. Chorley, the musical critic, was an intimate friend of Dickens. On one occasion he went to hear Chorley lecture on 'The National Music of the World,' and subsequently wrote him a very friendly letter criticizing his delivery, but speaking in high terms of the way he treated his subject.

Recitation of Thomas Hood’s poem ‘The Bridge of Sighs’ (written in 1844). Set to music by a group of American singers, the song favorably impressed Dickens, who praised the performance of it in a letter to the Countess of Blessington.In one of his letters he makes special reference to the singing of the Hutchinson family.(5) Writing to the Countess of Blessington, he says:

I must have some talk with you about these American singers. They must never go back to their own country without your having heard them sing Hood's 'Bridge of Sighs.'

Amongst the distinguished visitors at Gad's Hill was Joachim, who was always a welcome guest, and of whom Dickens once said 'he is a noble fellow.' His daughter writes in reference to this visit:

I never remember seeing him so wrapt and absorbed as he was then, on hearing him play; and the wonderful simplicity and un-self-consciousness of the genius went straight to my father's heart, and made a fast bond of sympathy between those two great men.

IN MUSIC DRAMA

Much has been written about Dickens' undoubted powers as an actor, as well as his ability as a stage manager, and it is well known that it was little more than an accident that kept him from adopting the dramatic profession. He ever took a keen interest in all that pertained to the stage, and when he was superintending the production of a play he was always particular about the musical arrangements. There is in existence a play-bill of 1833 showing that he superintended a private performance of Clari. This was an opera by Bishop, and contains the first appearance of the celebrated 'Home, Sweet Home,' a melody which, as we have already said, he reproduced on the accordion some years after. He took the part of Rolano, but had no opportunity of showing off his singing abilities, unless he took a part in the famous glee 'Sleep, gentle lady,' which appears in the work as a quartet for alto, two tenors, and bass, though it is now arranged in other forms.In his dealings with the drama Dickens was frequently his own bandmaster and director of the music. For instance, in No Thoroughfare we find this direction: 'Boys enter and sing ‘God Save the Queen’ (or any school devotional hymn).' At Obenreizer's entrance a 'mysterious theme is directed to be played,' that gentleman being 'well informed, clever, and a good musician.'

John Pyke Hullah (1812-1884), Musician, Composer and Music-Teacher: The young Charles Dickens made the acquaintance of twenty-three-year-old musician and composer John Hullah sometime around 1835—probably through his musical sister, Fanny, who, like Hullah, had studied both vocal music and piano at the Royal Academy of Music. Dickens, having in mind writing the lyrics for ‘a simple rural story’ in the tradition of the English ballad opera, agreed to collaborate with Hullah, not on a Ventian libretto as the young musician had originally proposed, but on what they entitled The Village Coquettes, a two-act sentimental/comic operetta set in the year 1829. It was presented as a ‘burletta’ at St. James's Theatre on 6 December 1836, starring John Braham as Squire Norton, John Pritt Harley as Martin Stokes, and Elizabeth Rainforth as Lucy Benson. After what he regarded as an unqualified success at the St. James's (but which the Athenaeum pronounced far less successful than Dickens's novels), Hullah turned his attention to the teaching of music. From 1844 to 1882, Hullah served with distinction as Professor of Vocal Music at King's College, London, and from 1872 also served as a government music inspector at the new publicly-funded grammar schools. Dickens was concerned in the production of one operetta--The Village Coquettes--for which he wrote the words, and John Hullah composed the music. It consists of songs, duets, and concerted pieces, and was first produced at St. James's Theatre, London, on December 6, 1836. The following year it was being performed at Edinburgh when a fire broke out in the theatre, and the instrumental scores together with the music of the concerted pieces were destroyed. Frederick G. Kitton, writing in The Dickens Country, his 1905 biography of the novelist and his illustrators, says, 'The play was well received, and duly praised by prominent musical journals.'The same writer gives us to understand that Hullah originally composed the music for an opera called The Gondolier, but used the material for The Village Coquettes. Braham, the celebrated tenor, had a part in it. Dickens says in a letter to Hullah that he had had some conversation with Braham about the work. The singer thought very highly of it, and Dickens adds:

His only remaining suggestion is that Miss Rainforth (6) will want another song when the piece is in rehearsal--'a bravura--something in ‘The soldier tired’ way.'

‘A bravura something’: From Thomas Arne’s Artaxerxes, Joan Sutherland sings the air ‘The Soldier Tir’d,’ a Dickens favorite that merits a mention in his Sketches by Boz, when Miss Evans and her friends visited the Eagle. During the concert 'Miss Somebody in white satin' sang this air, much to the satisfaction of her audience.We have here a reference to a song which had a long run of popularity. It is one of the airs in Arne's Artaxerxes, an opera which was produced in 1761, and which held the stage for many years. There is a reference to this song in Sketches by Boz, when Miss Evans and her friends visited the Eagle. During the concert 'Miss Somebody in white satin' sang this air, much to the satisfaction of her audience.

Dickens wrote a few songs and ballads, and in most cases he fell in with the custom of his time, and suggested the tune (if any) to which they were to be sung. In addition to those that appear in the various novels, there are others which deserve mention here.

In 1841 he contributed three political squibs in verse to the Examiner, one being the 'Quack Doctor's Proclamation,' to the tune of 'A Cobbler there was,' and another called 'The fine old English Gentleman.'

A recitation of Dickens’s ‘The Quack Doctor’s Proclamation,’ a political squib in verse the author contributed to the Examiner in 1841. As a song it was set to the tune of ‘A Cobbler There Was.’For the Daily News (of which he was the first editor) he wrote 'The British Lion, a new song but an old story,' which was to be sung to the tune of the 'Great Sea Snake.' This was a very popular comic song of the period, which described a sea monster of wondrous size:

One morning from his head we bore

With every stitch of sail,

And going at ten knots an hour

In six months came to his tail.Three of the songs in the Pickwick Papers (referred to elsewhere) are original, while Blandois' song in Little Dorrit, 'Who passes by this road so late,' is a translation from the French. This was set to music by R.S. Dalton.

In addition to these we find here and there impromptu lines which have no connexion with any song. Perhaps the best known are those which 'my lady Bowley' quotes in The Chimes, and which she had 'set to music on the new system':

Oh let us love our occupations,

Bless the squire and his relations,

Live upon our daily rations,

And always know our proper stations.The reference to the 'new system' is not quite obvious. Dickens may have been thinking of the 'Wilhem' method of teaching singing which his friend Hullah introduced into England, or it may be a reference to the Tonic Sol-fa system, which had already begun to make progress when The Chimes was written in 1844. (7)

There are some well-known lines which owners of books were fond of writing on the fly-leaf in order that there might be no mistake as to the name of the possessor. The general form was something like this:

John Wigglesworth is my name,

And England is my nation;

London is my dwelling-place,

And Christ is my salvation.

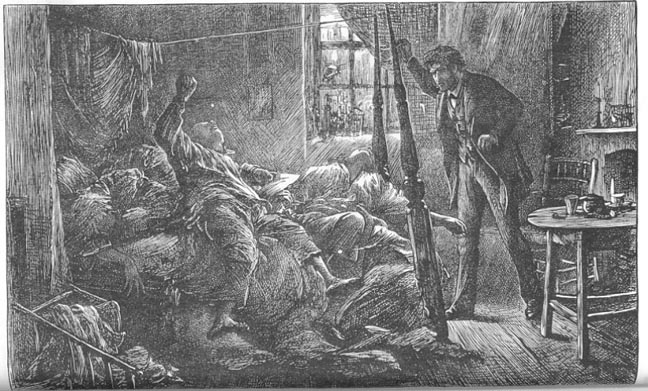

In the Court, an illustration by Sir Luke Fildes, was used as the frontispiece for Charles Dickens’s final novel, 1870’s The Mystery of Edwin Drood and Other Stories.(See Choir, Jan., 1912, p. 5.) Dickens gives us at least two variants of this. In Edwin Drood, Durdles says of the Mayor of Cloisterham:

Mister Sapsea is his name,

England is his nation,

Cloisterham's his dwelling-place,

Aukshneer's his occupation.And Captain Cuttle thus describes himself, ascribing the authorship of the words to Job-but then literary accuracy was not the Captain's strong point:

Cap'en Cuttle is my name,

And England is my nation,

This here is my dwelling-place,

And blessed be creation.It is said that there appeared in the London Singer's Magazine for 1839 'The Teetotal Excursion, an original Comic Song by Boz, sung at the London Concerts,' but it is not in my copy of this song-book, nor have I ever seen it.

Dickens was always very careful in his choice of names and titles, and the evolution of some of the latter is very interesting. One of the many he conceived for the magazine which was to succeed Household Words was Household Harmony, while another was Home Music. Considering his dislike of bells in general, it is rather surprising that two other suggestions were English Bells and Weekly Bells, but the final choice was All the Year Round. Only once does he make use of a musician's name in his novels, and that is in Great Expectations. Philip, otherwise known as Pip, the hero, becomes friendly with Herbert Pocket. The latter objects to the name Philip, 'it sounds like a moral boy out of a spelling-book,' and as Pip had been a blacksmith and the two youngsters were 'harmonious,' Pocket asks him:

'Would you mind Handel for a familiar name? There's a charming piece of music, by Handel, called the "Harmonious Blacksmith."'

'I should like it very much.'

Dickens' only contribution to hymnology appeared in the Daily News February 14, 1846, with the title 'Hymn of the Wiltshire Labourers.' It was written after reading a speech at one of the night meetings of the wives of agricultural labourers in Wiltshire, held with the object of petitioning for Free Trade. This is the first verse:

O God, who by Thy Prophet's hand

Did'st smite the rocky brake,

Whence water came at Thy command

Thy people's thirst to slake,

Strike, now, upon this granite wall,

Stern, obdurate, and high;

And let some drop of pity fall

For us who starve and die!We find the fondness for Italian names shown by vocalists and pianists humorously parodied in such self-evident forms as Jacksonini, Signora Marra Boni, and Billsmethi. Banjo Bones is a self-evident nom d'occasion, and the high-sounding name of Rinaldo di Velasco ill befits the giant Pickleson (Dr. M.), who had a little head and less in it. As it was essential that the Miss Crumptons of Minerva House should have an Italian master for their pupils, we find Signer Lobskini introduced, while the modern rage for Russian musicians is to some extent anticipated in Major Tpschoffki of the Imperial Bulgraderian Brigade (G.S.). His real name, if he ever had one, is said to have been Stakes.

Dickens has little to say about the music of his time, but in the reprinted paper called Old Lamps for New Ones (written in 1850), which is a strong condemnation of pre-Raphaelism in art, he attacks a similar movement in regard to music, and makes much fun of the Brotherhood. He detects their influence in things musical, and writes thus:

In Music a retrogressive step in which there is much hope, has been taken. The P.A.B., or pre-Agincourt Brotherhood, has arisen, nobly devoted to consign to oblivion Mozart, Beethoven, Handel, and every other such ridiculous reputation, and to fix its Millennium (as its name implies) before the date of the first regular musical composition known to have been achieved in England. As this institution has not yet commenced active operations, it remains to be seen whether the Royal Academy of Music will be a worthy sister of the Royal Academy of Art, and admit this enterprising body to its orchestra. We have it, on the best authority, that its compositions will be quite as rough and discordant as the real old original.

Fourteen years later he makes use of a well-known phrase in writing to his friend Wills (October 8, 1864) in reference to the proofs of an article.

I have gone through the number carefully, and have been down upon Chorley's paper in particular, which was a 'little bit' too personal. It is all right now and good, and them's my sentiments too of the Music of the Future.(8)

Although there was little movement in this direction when Dickens wrote this, the paragraph makes interesting reading nowadays in view of some musical tendencies in certain quarters.

____________________________________________

Footnotes:

1. In his speech at Birmingham on 'Literature and Art' (1853) he makes special reference to the 'great music of Mendelssohn.'2. Moore's Irish Melodies.

3. Moore.

4. 'Seven Dials! the region of song and poetry-first effusions and last dying speeches: hallowed by the names of Catnac and of Pitts, names that will entwine themselves with costermongers and barrel-organs, when penny magazines shall have superseded penny yards of song, and capital punishment be unknown!' (S.B.S. 5.)

5. The 'Hutchinson family' was a musical troupe composed of three sons and two daughters selected from the 'Tribe of Jesse,' a name given to the sixteen children of Jesse and Mary Hutchinson, of Milford, N.H. They toured in England in 1845 and 1846, and were received with great enthusiasm. Their songs were on subjects connected with Temperance and Anti-Slavery. On one occasion Judson, one of the number, was singing the 'Humbugged Husband,' which he used to accompany with the fiddle, and he had just sung the line 'I'm sadly taken in,' when the stage where he was standing gave way and he nearly disappeared from view. The audience at first took this as part of the performance.

6. Miss Rainforth was the soloist at the first production of Mendelssohn's 'Hear my Prayer.' (See The Choir, March, 1911.)

7. John Curwen published his Grammar of Vocal Music in 1842.

8. Quoted in Mr. R.C. Lehmann's Dickens as an Editor (1912).

NEXT MONTH: Chapter II: Instrumental Combinations--Violin, Violincello, Harp, Piano

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024