Roy Oribson went to dark places for his songs, and listening to them in the dark only made them more vivid, more wondrous in all their strange beauty.For Leah, Wherever She May Be

Taking Roy Orbison Very Personally

By David McGee

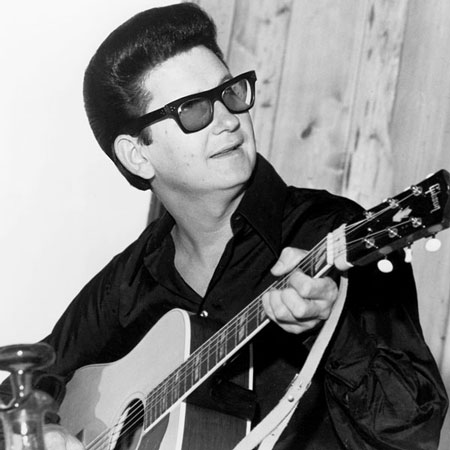

ROY ORBISON: THE MONUMENT SINGLES COLLECTION

Sony LegacyWhen contemplating Roy Orbison, music writers and musicians tend to speak in tones of hushed introspection. We take Roy Orbison’s music very personally, and the memory of it touches something fundamental, something spiritually resonant, in our souls, that visceral sense of being connected to the earth we walk on and to the people whose lives we touch and whose lives touch ours. It’s not easy to explain, any more than Orbison’s music is easy to explain. But we still reach out to it, loving it completely, without completely understanding it.

Averse to traditional song structures and standard narrative conceits, but also interested in connecting with the large mainstream audience, Orbison and his co-writers Joe Melson (early ‘60s) and Bill Dees (mid- to late ‘60s) not only wrote “In Dreams,” they wrote as if they were in a dream. Sometimes, when you awake from a dream, you have only a memory of the action, none of a conclusion; other times, you might awake in a panic, remembering little beyond your headlong rush towards disaster; still other times you might awake with a warm memory of revisiting someone whose very presence, who by simply being there with you, makes a cloudy day sunny, so to speak. Orbison and Melson may not have been the only writers who plumbed this dreamscape—although the only other who even approaches their mastery of it is the young Leonard Cohen—but they were alone in their fearless exploration of it. Though much is always made of the horrible tragedies that marred Orbison’s life—his first wife, Claudette (the subject of one of his earliest songs, “Claudette,” a hit for the Everly Brothers) was killed instantly in a motorcycle accident; and his first two sons died in a fire that consumed the Orbison home in Hendersonville, TN—and sometimes posited as reasons for his disturbing visions, but both of these cataclysmic events, which occurred in 1966 and 1968, respectively, antedated the songs on which his legend rests: after the mammoth, chart topping success of “Oh, Pretty Woman” in 1964, Orbison, though making some good, even exceptional records in the following years, did not make it back to the Top 20 until 1988’s career revitalizing “You Got It,” in the wake of his resurgence after David Lynch made Orbison’s “In Dreams” a signature moment in his oddball mystery, Blue Velvet. In fact, after 1968, following the deaths of his wife and his sons, and up to 1988, only 1967’s “Cry Softly Lonely One” and his warm duet with Emmylou Harris, 1980’s “That Lovin’ You Feelin’ Again,” made any appreciable commercial stir, and even those recordings peaked at #52 and #55, respectively. For 20 years, most of his singles did not chart at all in the U.S. (and he was recording steadily during that time, save for a five-year gap between 1981 and 1984 when he released no new music).

Roy Orbison, The Monument Singles Collection EPK, features interview with Monument founder and Orbison producer Fred Foster.No, Orbison was wrestling with something else in his glory years, some wrenching battle between id and ego, if you wanted to analyze it that way. Paranoia, dread, and fatalistic anticipation were the dominant states of mind of those early ‘60s gems—“Running Scared,” “Only the Lonely (Know How I Feel),” “Crying,” “In Dreams,” “It’s Over,” “Leah” (perhaps his most stunning moment on record, with a song that builds tension incrementally from verse to verse, without a chorus ever rearing its head)—but there were also moments of heartfelt tenderness in “Blue Angel,” “Blue Bayou,” and “Dream Baby.” After leaving Sun Records in 1957 following a fairly undistinguished tenure on Union Avenue (leaving behind a couple of good rockers in “Ooby Dooby” and “Rock House”), the Wink, Texas, native signed with RCA and was teamed in the studio with producer Chet Atkins. A fruitless year followed, but Atkins at least knew what he had in Orbison. On the few tracks they cut together, the producer sweetened up the arrangements with jazzy guitars, saxophones and close harmonizing background singers (which, to be fair, had also showed up on some of the later, Sam Phillips-produced Sun recordings). Of all the RCA sides, only the Boudleaux Bryant love song, “Seems to Me,” approached what became the signature Orbison style Orbison in the next decade. In 1958 he signed with the newly formed Nashville-based Monument label, which had been established by songwriter-producer Fred Foster and his partner, disc jockey Buddy Dean, whom Foster bought out in 1959.

Roy Orbison, ‘In Dreams,’ live in Australia 1972Whereas Atkins understood the magnitude of Orbison’s multi-octave voice and the textures the singer could command with it—Orbison’s vocal power is oft noted in music literature to the point of diminishing his mastery of tender, nuanced passages even as a maelstrom was swirling around him, which was the stuff of an intelligent, sophisticated vocal artist perfectly attuned to his songs’ emotional arcs and a big reason why the tortured scenarios his lyrics describe were so perfectly articulated in all dimensions—Foster saw the big picture. No disrespect to Chet Atkins at all—hey, even Owen Bradley famously passed on Buddy Holly (although why he did so has also been distorted to make Bradley seem unsympathetic to Holly’s vision)—but when Orbison and Melson came up with “Only the Lonely (Know How I Feel),” in 1960, Fred Foster was the right man in the right place at the right time to sculpt a soundscape worthy of Orbison’s Olympian despair. Foster believed in big productions—nothing about Orbison’s Monument recordings can be considered “stripped down" (those sessions were among the first in Nashville to use large string sections)—but he knew to keep the voice always hot in the mix. Orbison never battled the arrangements, but rather used his magnificent voice, and the feelings erupting in him, to establish the mood, then Foster’s arrangements ebbed and surged as the story developed, heightening the tension and mirroring the stories’ fevered, anxiety-riddled atmosphere. Orbison’s voice was one of the most remarkable instruments in rock, one he used to full effect, arguably never better than on “In Dreams” when the crying, operatic tenor rose from its assertive delivery to a plaintive wail, followed by a piercing falsetto shriek—always in tune, mind you—in a performance of breathtaking majesty and passion. Rarely have a producer, an artist and material been so ideally matched as when Fred Foster was behind the board rolling tape on Roy Orbison.

Roy Orbison, ‘Crying,’ live on The Roy Orbison Show, 1964Of course Orbison could kick it into a higher gear and rock out—he had, after all, started his career in a wild-ass rock & roll band in Wink, called, first, the Wink Westerners and then the Teen Kings—and in that mode he produced, in 1964, “Oh, Pretty Woman” (co-written with Bill Dees, as was one of Orbison’s greatest heartbreakers, “It’s Over”), his last #1 single, an instant rock ‘n’ roll classic with a good lyric, a beat you could dance to and further recommended for the playful side of the artist evident in the joy he takes in appraising the feminine pulchritude that has inflamed his libido, right down to the cat’s purr he effects and which became widely imitated by kids all over America when the song was riding high on the charts. Though less remembered as a rocker than as a balladee, Orbison's “Pretty Woman” still ignites a crowd whenever it's played.

Orbison fans all have their favorites, for various reasons having to do with wallowing in a moment of heartbreak, or recalling an impending date with the executioner when you knew a breakup was heading your way, something on that order. Everyone I knew was protective of his or her particular Roy Orbison song. I was no different. Which is why I could declare, above, “Leah,” the higher charting B side (#25) of the 1962 single with its rocking A side, “Working For the Man” (peaked at #33), “his most stunning moment on record.” Few are likely to agree with that assessment, given all the great records in the Orbison catalogue. It just so happened that Orbison’s “Leah” came along at the same time my own Leah—real name—popped up out of nowhere and Roy was suddenly singing my song.

Roy Orbison, ‘Leah,’ 1962We were in eighth grade, went to the same junior high school in Tulsa, but I didn’t know her, didn’t know her name, had not even recalled seeing her in school until she came on like the Oklahoma wind sweeping off the plains one night at the Mabee Red Shield Club, located on Harvard Ave., just beyond the tracks on the north side of town, across from the blazing, white-hot furnaces of the Hinderliter Heat Treating plant. Most people on that side of town had too much of nothing, but the Red Shield Club afforded us kids some well maintained facilities for sports of all kinds. I was in a furious game of basketball one night in the spring of my eighth grade year when I became aware of someone cheering my every move. Blonde haired, blue eyed, sturdy, athletically built Leah, it was, as I found out before the night was over. This was a very cool turn of events for yours truly, because I never made much time with blondes, no matter my exploits in various athletic endeavors. We just didn’t click. But I clicked with Leah. She showed up every week, she applauded every good thing I did, and when I fouled someone, she would take it out on the other player, claiming he had been at fault, not me. If I made an errant pass, the player I was trying to get the ball to clearly had cut the wrong way. When I scored—and frankly, I was scoring often in those games—she was quick to advise the kid defending me, “You can’t stop him! Don’t even try! Go home!” A couple of years later John Sebastian would describe her perfectly in song: "She's one of those girls who seems to come in the spring/one look in her eyes and you forget everything you had ready to say..."

Now you’re probably waiting for the big finish, how we took the action off the court, created friction and burst into flames. Didn’t happen. Leah was as elusive away from the court as she was omnipresent on its sidelines. She teased, she flirted, she put her head on my shoulder. I can still remember the smell of her dimestore perfume that to me was as fragrant as Chanel No. 5. Even now I catch a similar scent once in awhile on the streets of New York, and am sent reeling back in time. This was my Leah. Roy’s “Leah” has a tropical setting, with island drums thumping anxiously, a sweetly singing Hawaiian steel sighing softly in the background, gently swooping strings, an exotic melody buttressed by cooing female background vocalists. In the story, Roy is driven by his great love to go pearl diving, into the ocean depths, “to make a pretty necklace for Leah…the only girl for me.” Sure enough, something entangles his leg while he’s underwater, pulling him down to rest forever in a watery grave, his hands shut tight so that when he’s found “they’ll find the pearls for Leah.”

Turns out it’s all a dream—another anguished Orbison dream from which he awakes, suffering “heartaches and memories from the past/It was just another dream about my lost love.” Yet,when he drifts back into sleep, “in my dreams/I’ll be with Leah…”

God, this song is beautiful. And so was the real Leah. By summer’s end she was gone, to where I never knew. All she left behind were her pearls—the scent of her perfume on my sweat-soaked basketball shirt, the twinkle in her sky-blue eyes, the seductive, low laugh, those magnificent, architecturally exquisite legs with the slight back-of-the-thigh curve in the hamstrings. Never more our bodies to meet, we found each other in dreams, or in my dreams at least. Every night I knew: when sleep came, Leah was close behind.

‘Lonely days before they end/whisper secrets to the wind…’: Roy Orbison, ‘It’s Over,’ a BBC performance from July 11, 1975Fans of a certain generation know how real Roy Orbison’s songs were in their lives; how Roy seemed to know things about us we hadn’t even admitted to ourselves, much less to our best friends. In inducting Orbison into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1987, Bruce Springsteen observed, “Roy’s ballads were always best when you were alone in the dark.” Right. Roy went to dark places for his songs, and listening to them in the dark only made them more vivid, more wondrous in all their strange beauty. There was, and still has not been, anything quite like the Roy Orbison Monument singles. They’ve become something much bigger than mere songs, but to know exactly what that is you’ll have to ask all the other Orbison fans, because the experience of a Roy song is, it seems, singular to each listener.

Roy’s music has been well served in the reissue department, but on the occasion of what would have been his 75th birthday last month, the good folks at Sony Legacy have honored the man with a practically perfect double-CD/live DVD, beautifully packaged four-panel digipack with a 36-page booklet of complete sessionography and recording dates (release dates would have been nice and warranted, but they’re not here), chart showings, vintage photos and a liner note overview of the Monument years. The grainy DVD is of a live performance, vintage 1965, recorded for Dutch TV, when Roy was at his commercial peak. Titled Roy Orbison: The Monument Singles Collection, it is all wheat, no chaff—the A and B sides Orbison recorded for the label between 1959 and 1966 in lovingly restored mono mixes available for the first time since the release of the original seven-inch vinyl singles. ‘Tis a puzzlement why the chronology is so screwy—it conforms to no detectable logic relating to recording dates or chart history, the A and B sides are on separate discs, and three singles are designated as “bonus tracks”—but the music is all there, even if its timeline is out of whack. For those who simply want the cream of the Orbison Monument crop in a tidy package, a single disc, The Monument Singles: A Sides (1960-1964), has been released from this collection.

See you in dreams, dear Leah, wherever you are. Bring the pearls.

Roy Orbison: The Monument Singles Collection is available at www.amazon.com

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024