The Search for Thomas F. Ward, Delius's Teacher

By Don C. Gillespie

In his book The Search for Thomas F. Ward, Teacher of Frederick Delius, author Don C. Gillespie traces the peripatetic life of Brooklyn-born organist Thomas F. Ward as it intersected with that of Frederick Delius when the latter came to Florida to work on an orange plantation and befriended the black workers, whose old slave songs mesmerized the young composer and worked their way into his beloved composition Appalachia. Ward became Delius’s teacher and had a profound influence on the headstrong composer. Author Gillespie properly identified Ward’s influence on Delius, as the latter’s link to the black culture he found when he came from Europe to manage an orange plantation in Florida. In this excerpt, Gillespie recounts how he began his search for Thomas F. Ward, a near-forgotten figure in music history who played a decisive role in Delius’s development as a composer.

We might now ask: What exactly is the point in spending years in attempting to resurrect the American teacher of Frederick Delius? Why would one invest such an enormous amount of time on such a seemingly unimportant musicological project? Reactions to my project have varied from bemused puzzlement to shared excitement. On December 18, 1986, the legendary music lexicographer Nicolas Slonimsky answered a letter of mine with the query: “What on earth possessed you to travel all over the land in search of the teacher of Delius? Who cares? Anyway, I for one do not intend to follow in your footsteps in the marshes of Florida or search for his remains in the cemeteries.” (But he then offered some valuable genealogical advice.) The opposite reaction came from the great Delius scholar and his amanuensis, Eric Fenby, on June 30, 1986: “I have been waiting half a century for the letter you sent me on Thomas Ward. …Your intensive researches into what happened to him prove you to be the one man likely to solve this mystery. You have my full support.” He added: “It is a hundred years this month since Delius and Ward parted. Clearly, Delius regretted having lost touch with him.”

I confess that I accept the premise that the American influence on Delius’s career and music may have been the most important one--more decisive than that of Edvard Grieg, which followed, or the various currents of modernism that Delius encountered in Europe on his return from America and eventual settlement in France. It is my belief that Delius would not have become the composer we know today had he not encountered Ward and that certainly the direction of his music would have taken without Ward and Florida would have been quite different; it would have been much less original without the mélange of American and European influences that underlies his special sound world.

Only a few facts were known about Thomas F. Ward in the mid-1980s when I began this project. I have accepted only those statements that derive directly from Delius himself, for where Ward is concerned the tendency to embellish and fantasize has been irresistible to most writers.

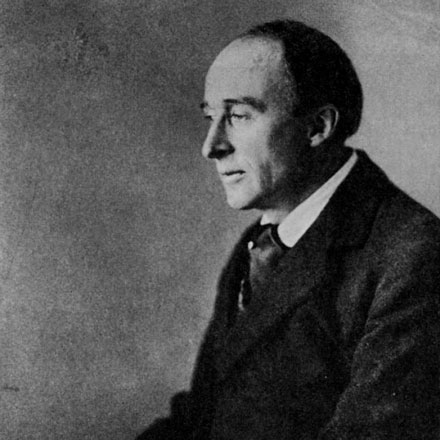

Frederick Delius: Under Thomas F. Ward’s tutelage, writes Philip Heseltine (aka Peter Warlock), ‘The young composer developed very rapidly. He worked with a demoniacal energy, and in a short time he had as good a knowledge of musical technique as the average student at the institutions acquires in the course of two or three years.’Interestingly, Ward’s name does not occur at all in the first scholarly work on Delius, a brief monograph in German by Max Chop published in 1907 when Delius’s music was gaining wide acceptance in Germany. Chop alludes to the exotic atmosphere of Florida (Appalachia, alligator hunting, black servants, etc.) but does not mention Ward. Perhaps the full Florida story was too personal to be revealed to an objective German Musikwissenschaftler--to a stranger.

Nor is Ward mentioned in the lengthy and perceptive biographical portrait of Delius by the American composer Edward Burlingame Hill in 1909, shortly before Delius’s first important American premiere: the performance of Paris by the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Max Fiedler on November 26, 1909. On the contrary, Hill informs us that in Florida Delius “pursued his musical studies alone” while reflecting upon the tradition of the great masters of the past.

Strangely, the first known reference to Ward and Delius appears not in Europe, where Delius was well known, but in New York City, where his music was still a novelty. On the occasion of the American premiere of Delius’s Piano Concerto in New York City on November 26, 1915, by the Australian pianist Percy Grainger, H.E. Krehbiel, the eminent music critic of the New York Tribune, mentioned a “New York organist” who has strongly influenced Delius’s music:

[Delius] wanted to be a musician, his father wanted him to be a merchant, and as a sort of compromise he was sent to Florida, when he arrived at his majority, to manage an orange grove which his father had bought for him. In Florida he “studied music and nature,” guided in the former study by a New York organist, who had gone to Florida for his health. This organist, whose name has not been confided to us, lived on Delius’s orange grove for several months, and as a recent English sketch puts it, “imparted to his host all the musical technique that can be taught in a place where practical experience is impossible. (November 21, 1915)

I have not yet identified the written “recent English sketch” from which Krehbiel might have drawn his remarks. Perhaps the source was an oral one. Unquestionably, this information must have come from Percy Grainger himself, who had recently moved from London to New York. The famous composer-pianist was an intimate friend of Delius and an enthusiastic proponent of his music in America. In late 1915 Grainger was, in fact, making zealous propaganda for both Delius’s Piano Concerto and for his own appearance with the New York Philharmonic in Carnegie Hall. Only to his closest musical colleague would Delius have suggested that the name of Ward not be “confided.” But why?

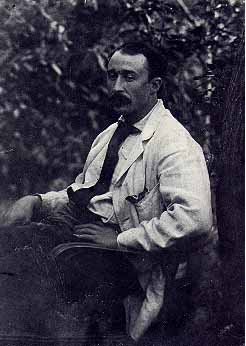

As a young man Frederick Delius had contracted syphilis which, apparently left untreated for too long, rendered him blind and paralyzed near the end of his life…Thomas F. Ward’s name first appears in the 1923 study of Delius by Philip Heseltine (alias Peter Warlock), as remembered by the composer almost forty years after his Florida experience. There we read the story of the chance meeting in 1884 of young Fritz Delius the would-be orange grower, sent to Florida to escape the lure of music, and Tom Ward, the new organist of Jacksonville’s Catholic Church, in Merryday & Paine’s music store on West Bay Street near the Jacksonville waterfront. I will quote Heseltine in some detail, as his account touches on an area of controversy concerning Ward’s Brooklyn background. The words of Heseltine, an intimate friend of Delius and worshiper of his music--and a master of the English language--sound a bit like scripture:

Now, it happened that while he [Delius} was trying one of the pianos that were offered to him, there passed by the open door of the shop an individual who was so struck by the beauty of the sounds proceeding from inside that he came in and begged to be made acquainted with the young man who was playing. This individual was Thomas F. Ward, organist of the Jesuit Church of SS. Peter and Paul in Brooklyn, the son of a Spanish priest and an Irish kitchen-maid. He was inclined to consumption and had been sent by the Fathers of his Church to the South in the hope of restoring his health. It was a romantic encounter. A lively sympathy between the two musicians led to their returning together to the orange grove with the piano. Ward was an excellent musician. …and it is not too much to say that the whole of Delius’s technical equipment is derived from the instruction he received from Ward in the course of his six months’ sojourn on the plantation. The young composer developed very rapidly. He worked with a demoniacal energy, and in a short time he had as good a knowledge of musical technique as the average student at the institutions acquires in the course of two or three years. In his teaching, Ward wisely confined himself to counterpoint, seeing that his pupil’s natural instincts had already provided him with a finer sense of harmony than could ever be gained from textbooks and treatises.

Heseltine further asserts that Delius learned even more from Ward’s “admirable performance of the great masters--especially Bach, of whom his knowledge equaled his love--on the piano at the plantation and on the organ of a Roman Catholic Church in Jacksonville, which was occasionally visited for this purpose.

The second valid source about Ward is Eric Fenby’s memoir of 1936, Delius As I Knew Him (the source of Ken Russell’s film biography of Delius’s last years, Song of Summer). According to Fenby, Delius himself related that:

“It was not until I began to attend the harmony and counterpoint classes at the Leipzeig Conservatorium that I realized the sterling worth of Ward as a teacher. He was excellent for what I wanted to know, and a most charming fellow into the bargain. Had it not been that there were great opportunities for hearing music and talking music, and that I met Grieg, my studies at Leipzeig were a complete waste of time. As far as my composing was concerned, Ward’s counterpoint lessons were the only lessons from which I ever derived any benefit. Towards the end of my course with him--and he made me work like a slave--he showed wonderful insight in helping me find out just how much in the way of traditional technique would be useful to me.” After a pause, in which he appeared to be deep in thought, he added, “And there wasn’t much. A sense of flow is the main thing, and it doesn’t matter how you do it so long as you master it.”

Fenby added, “Unhappily, Ward did not live to see his pupil famous, but died of tuberculosis, after spending the last years of his short life in a monastery”--a statement which I eventually discovered to be partially inaccurate.

Ward instilled in Delius the virtues of discipline and hard work at one’s profession. “The habit of regular work which he had acquired from Ward, out there in Florida, never left him.” Fenby wrote: “Ward, a devout Catholic…had known his pupil for what he was--a headstrong, boisterous, hot-blooded young fellow with more than a streak of the adventurer in him--and he had taken him well in hand.” This Catholic-instilled discipline was enough to sustain Delius years later, “even amid the thousand and one distractions of Paris,” as Fenby expressed it. He regretted that Delius did not take on even more of Ward’s Catholic character, “not so much as to make his pupil a Catholic, but at least a believer.” Fenby added nothing significant to this portrait of Ward in his later monograph Delius, but in 1984 he repeated Delius’s account of his American teacher, furnishing a few significant details about Delius’s escape to America and his exotic new locale:

“Florida! Ah! Florida! I loved Florida--the people, the country--and the silence! …I wanted to get away as far as possible from parental opposition to my becoming a musician. …Just think, I met Thomas Ward, an organist, by chance whilst choosing a piano in a Jacksonville music-store! I didn’t realize what a good teacher he was until I went eventually to Leipzeig Conservatoire. The professors there had no insight whatever compared with his. His instruction was intuitive; just what I needed. He was a fine fellow, too, and I was grieved when he died of consumption some years later.

[At Solano Grove] I used to get up early and be spellbound watching the silent break of dawn over the river; Nature awakening--it was wonderful! At night the sunsets were all aglow--spectacular. Then the coloured folk on neighboring plantations would start singing instinctively in parts as I smoked a cigar on my veranda.”

In response to a hopeful inquiry of mine concerning Ward, Fenby could only offer that he was, according to Delius, “a most endearing man of the highest integrity and personal charm.” As Fenby had described him to me, one did not ask questions of Delius; his first interrogation of the composer at Delius’s home in Grez-sur-Loing brought a sharp rebuke: “Never ask questions, boy: To answer them is weak!”

The young Delius, during his ‘Florida experience,’ when he met his teacher, Thomas F. WardThe ties between Delius and Ward were apparently severed after 1885. After a year and a half in Florida, Delius left his neglected plantation to his newly arrived brother and, with a letter of recommendation from Tom Ward, moved to Danville, Virginia, in the fall of 1885, where he taught for awhile at a girls’ finishing school before returning in June 1886 to Europe and eventually fame. When, in the spring of 1897, Delius returned to Solano Grove during his last trip to America, he heard the news that his friend Ward had died in the mysterious circumstances he later related to Fenby.

No letters between Delius and Ward have survived. Apart from a poem by Ward in one of Delius’s music sketchbooks, there exists only a volume of the works of Lord Byron inscribed “From Thomas F. Ward, Jacksonville, Florida, to Fritz Delius, Leipsic, Germany,” in which a flower had been pressed. Ward had marked in pencil the following passage from Byron’s “Hints from Horace”:

The youth who trains, or runs a race,

Must bear privations with unruffled face

Be call’d to labour when he thinks to dine,

And, harder still, leave wenching, and his wine.That is the complete record of Ward that can be reliably traced to Delius. All other accounts in which Ward is described, sometimes at length (including those by Delius’s sister Clare and by the noted Florida historian Gloria Jaboda), have served only to muddy the waters. Clare Delius recounts, in the midst of such embroidery, that “Fred…often told me in after years how he learned more from Mr. Ward than he ever learned from anybody else.” Gloria Jahoda, whose contributions to Delius research is in many ways admirable, relates as facts (not as the intuitions they are) how, in company with Delius, Ward’s mind raced with talk of Mendelssohn’s oratorios, how he told Delius about a pianist named Louis M. Gottschalk, and so on. Another writer, following Jahoda, even reveals that the contents of Delius’s first meal down on the plantation consisted of “pork and field peas.”

Deems Taylor (1885-1966), the popular American composer, writer, and radio commentator, provided possibly the most fanciful account of the two musicians’ encounter. In his best selling 1937 music appreciation text Of Man and Music, an uncharacteristically shy Delius and an unusually loquacious Ward made an appearance in a book that by 1945 had gone through twelve printings and 47,000 copies:

“I hope you’ll forgive the intrusion,” [Ward] said, “but as I was coming up the street I heard someone playing in here; and I don’t hear many good pianists in this part of the country. I had to come in and find out who it was. Besides, I’m very curious about the music. I’m pretty familiar with organ and piano music, but that piece you were just playing is absolutely new to me. What is it?”

“The young man [Delius] seemed a little embarrassed. “Why…er,” he stammered, “it’s…it’s really nothing at all. I was just improvising.”

Ward, whose interest by this time was beginning to border on excitement, began to ask questions.”

The romanticizing of the Delius-Ward story, plus the scant facts available, have caused some reputable scholars to downplay Ward’s influence on Delius; among them is the foremost authority on Delius’s stay in America, the historian William Randel. But we are forced to consider the fact that Delius never wavered in his assertions about Ward’s influence. After a concert in St. Augustine, Florida, the pianist Ethel Bartlett described to a local historian her visit to Delius at Grez toward the end of his life. Delius told her that “there by the St. Johns he had developed traits of character that had been a never failing source of strength all his life” and that he “could not say too much of the debt he owed for the instruction received from [Thomas Ward].” Despite his anti-Christian, often blasphemous stance toward all religions in his later years, Delius never betrayed his friendship with the Catholic friend of his youth, whose religious belief confronted the atheistic young composer head-on in 1884.

Thomas F. Ward, however, remained a blank page: the missing link of Delius’s biography. To bring him out of the shadows, to reveal the mysterious musician Delius considered the major influence on his artistic development, and “a most charming fellow into the bargain,” we must begin by going back to the nineteenth century.—

Read this excerpt plus more of the book online at Google Books

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024