Elvis ’69: the artist who so profoundly changed the world even as he increasingly withdrew from itWhat Goes Up Must Come Down

By David McGee

Elvis Country: Legacy Edition

Elvis Presley

RCA/LegacyJune 1970

04 Thursday

Elvis begins five days of recording at RCA’s Studio B in Nashville, reporting each evening at 6:00 P.M. and working until the dawn hours. During the thirty months that have elapsed since Elvis’ last Nashville session, the studio has been upgraded from a simple four-track system to (briefly) an eight-track and now to a sixteen-track board. While this allows for greater ease of overdubbing, it also requires a greater degree of technical facility to access the advances, and Felton’s main strength has never been technology. Nonetheless, he goes into the sessions with a great sense of optimism, sure of both his artist and the musicians who will be backing him--for Felton has finally reconstituted the studio band. Gone are Scotty Moore and D.J. Fontana, Elvis’ original accompanists, as well as pianist Floyd Cramer, bassist Bobby Moore, drummer Buddy Harman, and the Jordanaires. In their place, working with Elvis for the first time are Norbert Putnam on bass and Jerry Carrigan on drums, along with multi-instrumentalist Charlie McCoy, pianist David Briggs, and guitarist Chip Young, who have appeared on various sessions since the mid-sixties, James Burton, the guitarist in Elvis’ show band takes over lead guitar in an ensemble that Felton believes will provide the kind of energy and expertise that the American session players were able to offer. The first night runs more than ten hours and proves highly productive, with eight songs completed, spanning every style from gospel to bluegrass jams to contemporary pop (an example of the latter would be the grandiloquently realized “I’ve Lost You,” soon to become Elvis’ next single).05 Friday

Maintaining the same level of energy and commitment that he showed on the previous night, Elvis completes another seven masters, including a raucous jam on a combination of Muddy Waters’ “Got My Mojo Working” and Jay McShann and Priscilla Bowman’s “Hands Off,” as well as a beautifully sung cover of Simon and Garfunkel’s “Bridge Over Troubled Water.”07 Sunday

Starting at 6:00 P.M. and not quitting until 4:30 A.M., Elvis seizes on older country-and-western material such as Ernest Tubb’s “Tomorrow Never Comes,” Bob Wills’ “Faded Love,” and Eddy Arnold’s “I Really Don’t Want to Know.” The almost accidental result is a collection of songs that forms the basis for a “concept album,” Elvis Country.

Elvis, a cover of Ernest Tubb’s ‘Tomorrow Never Comes,’ from Elvis CountryDecember Record Release

Single: “I Really Don’t Want to Know” (#21)/”There Goes My Everything” (shipped December 8). The movie soundtrack album, That’s The Way It Is, has been in stores less than a month when RCA releases Elvis’ fifth single of the year as a forerunning to the forthcoming Elvis Country album. The A-side, an Eddy Arnold (and Solomon Burke) classic, does not chart particularly well but sells close to 700,000 copies.January 1971 Record Release

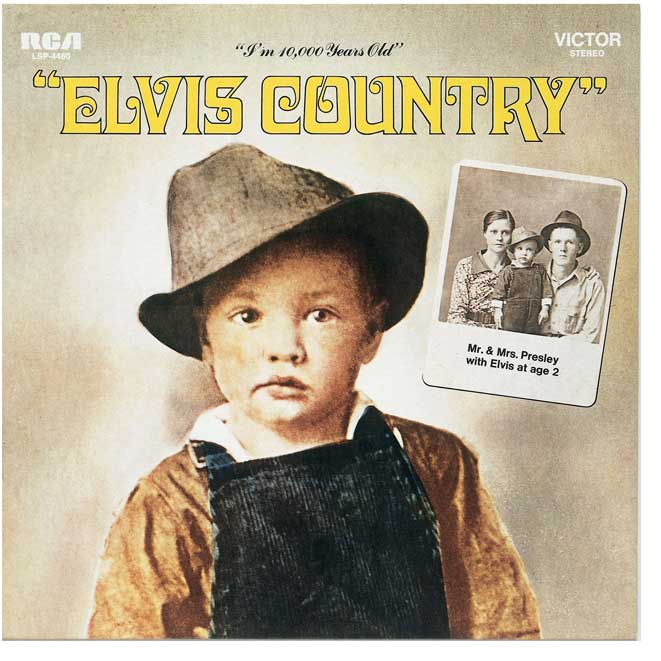

LP: Elvis Country (#12). This album of country material is critically well received and offers a puzzling “album concept,” as snippets of the Golden Gate Quartet’s “I Was Born 10,000 Years Ago” are interspersed between the cuts--but neither critical acceptance nor theme nor performance pushes the record beyond the customary half-million copies.From Elvis Day By Day: The Definitive Record of His Life and Music, by Peter Guralnick and Ernst Jorgensen (Ballantine, 1999)

***

… And now at a time when it seemed as if his career must sink beneath the accumulated weight of saccharine ballads and those sad imitations of his own imitators, Elvis Presley has come out with a record which gives us some of the very finest and most affecting music since he first recorded for Sun almost 17 years ago.

Elvis Country is, obviously, a return to roots. If nothing else the album cover, with its picture of a quizzical Depression baby flanked by grim unsmiling parents,, would tell you so. Its subtitle, too, “I’m 10,000 Years Old”--taken from a song which weaves mystifyingly all through the record, fading in and out after every cut--should give a clue to its intent. And the selection of material, its manner and presentation, from the Bill Monroe tune which echoes “Blue Moon of Kentucky,” the very first Sun release, to the Willie Nelson and Bob Wills blues, is a far cry from the slick countrypolitan which Elvis has been leaning on so heavily lately in his singles releases.

But it’s the singing, the passion and engagement most of all which mark this album as something truly exceptional, not just an exercise in nostalgia but an ongoing chapter in a history which Elvis’ music set in motion. All the familiar virtues are there. The intensity. The throbbing voice. The sense of dynamics. That peculiar combination of hypertension and soul. There is even, for those who care to recall, a frenzied recollection of what the rock era once was, as Elvis takes on Jerry Lee Lewis’ masterful “Whole Lotta Shakin’” and comes out relatively unscathed.

(Excerpt from a review of Elvis Country by Peter Guralnick, published in Rolling Stone, March 4, 1971

***

Thus the path from conception to execution to release to appraisal of Elvis Presley’s extraordinary 1971 album Elvis Country. In toto, his combined tally of 23 studio albums and 19 soundtrack LPs (many of which contain non-soundtrack cuts to flesh them out to full album status) includes indisputably great records; some good but inconsistent outings containing flashes of brilliance; some uninspired performances (notably on the post-‘50s soundtracks); and a requisite disaster or two. Only one of these--only one--could be described as mysterious, and that one is Elvis Country.

What’s mysterious about it? Not Elvis’s performances: released in January 1971, Elvis Country followed two of the King’s finest LPs in 1967’s gospel outing How Great Thou Art, and the first studio album of his post-comeback years, 1969’s stunning, Chips Moman-produced From Elvis in Memphis; two months before Elvis Country surfaced, some of the tracks left off From Elvis in Memphis showed up on the studio portion of the double album From Memphis to Vegas/From Vegas to Memphis, one half of which was his first live album, recorded at the International Hotel in Las Vegas in August 1969. Elvis was hot and hungry; what Peter Guralnick heard as “some of the very finest and most affecting music since he first recorded for Sun almost 17 years ago” was a continuation of what we’d been hearing from the Hillbilly Cat since the 1968 comeback special, especially in that show's electrifying in-the-round segment when he, Scotty Moore, D.J. Fontana, Charlie Hodge and Alan Fortas ripped and roared, raw and built for speed, through some of Elvis’s fiery hits from his early years, starting with “That’s All Right, Mama.” At that moment everything that was great about Elvis, everything that he did better than everybody else, was in full bloom, and all those who had hung with and believed with him through the dreary movie years--because we knew the dirty little secret that buried on those soundtrack albums were some powerful ballads and sizzling rockers never issued as singles--had their faith vindicated.

From Elvis Country: ‘It’s Your Baby, You Rock It’ (Charlie McCoy, harmonica)The only misstep here is the album’s first cut, a rote cover of the big Anne Murray hit penned by Gene McLellan, “Snowbird,” hewing to the Murray arrangement and lacking the daring or inspiration informing the rest of the numbers. Even so, if the music is ordinary, Elvis’s sensitive vocal, riding airily along the melody line, carrying equal measures of weary resignation and wary optimism (“…sings to me of flowers that will bloom again in spring”) in a heartfelt performance, is striking. From there he’s sailing. He completely reimagines Ernest Tubb’s brisk-paced “Tomorrow Never Comes” by starting off in a somber, deliberate mode, working with deep, bluesy feeling in the opening verse as he’s backed by drummer Jerry Carrigan’s steady march rhythm and not much else beyond Norbert Putnam’s subtle bass line; but as the song progresses the arrangement progressively blooms with the entrance of a surging, driving horn section along with the Jordanaires’ rich background support and a flurry of strings; finally, a majestic closing crescendo bursts forth, taxing Elvis’s upper range--but he nails his part--and putting the capper on a gripping, anguished reading. The version of Bill Monroe-Lester Flatt’s bluegrass treasure “Little Cabin On the Hill” dispenses with big effects in favor a tough, shuffling, small combo feel, driven by acoustic guitar with Charlie McCoy’s sputtering harmonica adding some zest while Elvis plays the vocal low-key, in subdued contrast to the music’s bustle, in an effective conjuring of the broken-hearted narrator’s abiding sorrow. This pattern is repeated in a spare, blues-drenched reading of Willie Nelson’s “Funny How Time Slips Away,” in which Elvis’s disarming nonchalance is but a flimsy mask revealing more than it conceals about the enduring hurt flaring within when he encounters an old flame, and a big, bruising production of Jack Greene’s 1966 smash, “There Goes My Everything,” with what is practically a big-band blues arrangement of Eddy Arnold’s ballad “I Really Don’t Want to Know” sandwiched between them.

from Elvis Country: Bill Monroe-Lester Flatt’s ‘Little Cabin On the Hill’So it goes, with Elvis the master of all he surveys, in the defiant kissoff he so casually announces in an otherwise gentle rocker, “It’s Your Baby, You Rock It”; in the lowdown but undaunted spirit he projects in “I Washed My Hands In Muddy Water,” as David Briggs reels off some Jerry Lee-like glissandos, James Burton injects snarling guitar lines, the horns juke and jab and Charlie McCoy honks away on harp--the whole enterprise has such energy as to incite Elvis to spur the band on with excited exhortations as he improvises lyrics when things get rolling towards a furiously pumping coda; in the deep, controlled rumblings of self-regret that consume the entirety of “The Fool,” a song he’d loved in its original 1956 rockabilly incarnation by Sanford Clark but which he tackles here as a dirty blues with a bit of stomp in an arrangement dominated by James Burton’s stinging lead guitar and McCoy’s shimmering, moaning harp. With David Briggs so often evoking Jerry Lee’s pounding piano, it’s interesting that he’s not the dominant instrumental voice on a fast and furious “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On,” with those duties falling to guitarist Burton and at the end, to drummer Jerry Carrigan, as per Elvis’s shout, “Take it out, Jerry! Take it out!” It’s as if Elvis conceded he couldn’t match the Killer’s original version but could bring some heat on his own terms; similarly, Bob Wills’s “Faded Love” is no longer the rich western swing ballad of Wills’s original or a sumptuous, orchestrated pop-country weeper (a la Patsy Cline’s immortal rendition) but rather a jaunty, midtempo southern rock ‘n’ soul workout with brittle, wailing guitar courtesy James Burton and a horn section pumping and burping along as Elvis swaggers through the lyric--again, a concession and a triumph all at once.

In concert, Elvis performs Willie Nelson’s ‘Funny How Time Slips Away.’ The studio version is included on Elvis Country.So where’s the mystery? The mystery, friends, is in the hard driving jam on an old country gospel tune, “I Was Born About Ten Thousand Years Ago,” first recorded by Kelly Harrell in 1925; by the time Elvis got around to it, the song had been covered by artists ranging from the Golden Gate Quartet to The Seekers to Odetta. Elvis Country takes its subtitle--I Was Born Ten Thousand Years Ago--from this song, but Elvis takes his cue from none of the aforementioned artists. He simply cuts out and leads the band on an unrelenting charge, which posits the singer as having witnessed pretty much everything that’s happened since history began, which in turn leaves an open question as to whether the singer is really God. The full version of “I Was Born About Ten Thousand Years Ago” is included as a bonus cut on this reissue. On the original album it’s heard only in fleeting snippets, fading in and out between tracks (in one instance purely instrumental, no vocal)--that’s the “concept.” It serves a purpose in enhancing the mood of the ballads and revving up the energy for the rockers, but beyond that only mystery remains. Neither Elvis nor producer Felton Jarvis ever explained why they chose to use the song in this manner, nor has anyone else connected with the album, if they even know. But the more the song pops up, the more eerie it starts to sound, until it becomes a haunting sub-theme; destined to remain so, it leaves hanging a second question question: was Elvis using the song to comment on himself in his own time, or to make a statement about the toll fame had exacted from his soul? In a real way, those tantalizing between-songs annotations remind us of how little we really knew of the substance of the artist who so profoundly changed the world even as he increasingly withdrew from it.

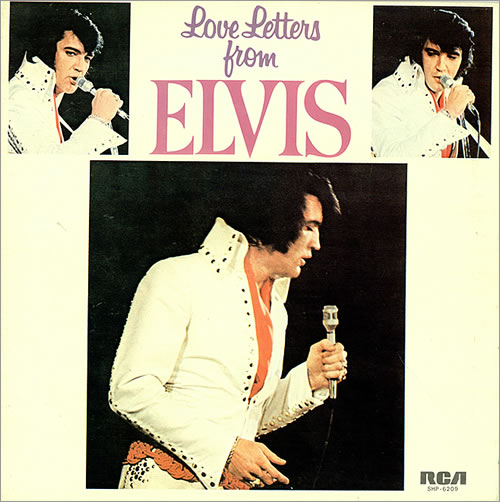

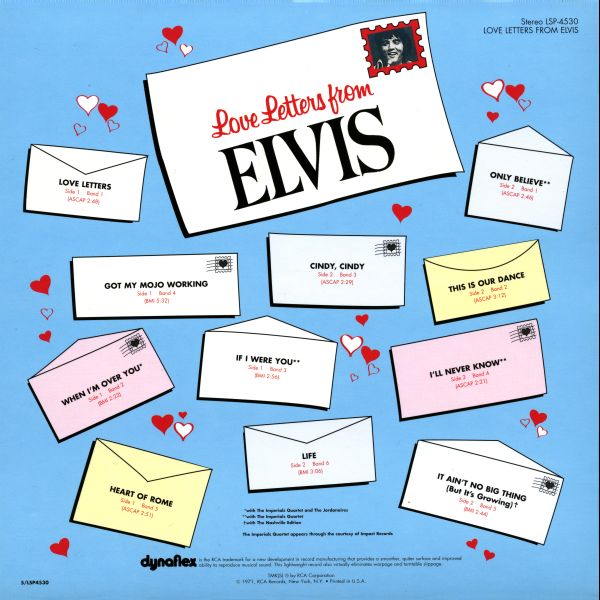

The enthusiasm Elvis Country generated among critics in January waned with the June ’71 release of Love Letters from Elvis. The problems began with tacky front and back cover designs that would merit failing grades in today’s web graphics courses but in their own day were as cheesy as the covers designed for Elvis’s RCA Camden budget label releases. It was as if the RCA art department was plain exhausted after inspiration visited on Elvis Country and threw together the simplest, most rudimentary elements at hand to get the project off the drawing board and out the door.

Elvis, the 1970 version of ‘Love Letters,’ opens Love Letters from Elvis on a promising noteThe album begins in a promising way--really promising, in that the old Kitty Kallen love ballad, “Love Letters,” inspired one of Elvis’s most sophisticated and probing vocal attacks--introspective, ruminative and lonely, deeply drenched in blues phrasings, daring in the way he stretched out the melody line with extra syllables to add tension to the track or, indeed, clipped a phrase abruptly and then paused--“love letters straight”--one beat--“from your heart…” in a way that provided a momentary emotional lift to the performance. The strings are soft and restrained, with elegant but reined-in swirls altering the texture of an otherwise understated wash; a flutter of woodwinds sneaks into the soundscape, so subtle as to be almost undetectable; and David Briggs’s moody piano shadows Elvis and clips the ending with a flicker of glissando. It’s a great start, stunning really. (It has some notable detractors, however: the respected Elvis historian/archivist Ernst Jorgensen, who has steered the Elvis reissue program for years, and who co-produced this collection with Roger Semon, considers this version inferior to the more understated treatment Elvis gave it in a 1966 session, as Jorgensen opined in his essential guide to the Presley recording career, Elvis Presley: A Life in Music). A nice country heartbreaker keyed by guitarist James Burton’s spiky opening riff, “When I’m Over You” features a heartfelt Elvis vocal; Burton keeps crafting energizing riffs, but soon enough the tough-minded track is subsumed by a clumsy string arrangement and a big, shouting background chorus completely inappropriate to the mood Elvis and the basic band had created, thus wasting a good song from Shirl Milete, whose unforgiving “It’s Your Baby, You Rock It” was an Elvis Country highlight. The mistakes of “When I’m Over You” are repeated throughout Love Letters from Elvis: “Heart of Rome,” not a stellar song on balance, is blessed with a fully engaged Elvis, singing plaintively and bruised, but the strings are totally weird, someone is way out of their league singing “la-la-la-la-la”’s with him, and given the song title and lyric sentiments the Mexicali horns don’t make much sense; Shirl Milete comes a-cropper with “Life,” a pretentious “big statement” song musing on the origins of the universe, our planet and evil, with a portentous chorus, cumbersome strings and a flute fluttering around to little effect, as Elvis makes what he can of a rigid arrangement, which is not much.

On the other hand, Elvis delivers a terrific, hard driving workout on “Got My Mojo Working/Keep Your Hands Off Of It” that elevates to a frenzy about midway through, as the band keeps kicking, the horns pump boisterously, the gospelized gals singing backup get the spirit and Elvis pushes the pedal to the metal, driving the band and his fellow vocalists to greater intensity, shouting encouragement to all and sending it to a white-hot finish with a fiery call-and-response on “got my mojo workin’!” until one final, heated crescendo erupts, after which you can hear a heavy breathing Elvis laugh out loud, a free and delighted exultation worthy of the effort expended for nearly five minutes on the number. A similar type of fury propels “Cindy Cindy,” an old public domain number retooled by Elvis favorite Ben Weisman, Buddy Kaye and former Ed Wood starlet Dolores Fuller (who had penned one of Elvis’s greatest love ballads of his early post-Army years, ‘Big Love, Big Heartache,’ for Roustabout) into a furious, stomping come-on that the King eats up with a strong, blues-based shout over a tough-minded arrangement stripped down to the basic band and Charlie McCoy’s wailing, exuberant harmonica.

Elvis, ‘Cindy Cindy,’ from Love Letters from Elvis (written by Buddy Kaye, Ben Weisman and former Ed Wood starlet Dolores Fuller)If there is a mystery surrounding Love Letters from Elvis it concerns the question of how, when its songs were recorded at the same time as those heard on Elvis Country (in several sessions in June 1970), so many arrangements could have gone awry and veered into schlock where so many others were lean, nimble and energized. Clearly, an accident of song selection and album sequencing made Elvis Country a focused, thoughtful exploration of this great artist’s deepest roots, whereas the choices that were left him afterwards turned Love Letters from Elvis into a dress rehearsal for some of the worst excesses of the Vegas years. You have to wonder why Elvis let it happen.

Thoroughly dismembering the album in a March 22, 1971, review in Rolling Stone, Jon Landau (now Bruce Springsteen’s manager) posited the following observation: “The question to ask is, who is this music for? Somehow I expect that even those who have come to Elvis mainly through his nightclub performances expect a little more than they are given on Love Letters from Elvis. And those of us who have loved him from the beginning, and know that he could still be doing it, because every now and then we can still hear him doing it, can only turn away in disgust from this sort of thing.” That’s not a love letter, but it’s the truth. The truth hurts, but, as the Everly Brothers reminded us so long ago, so does love.

Elvis Country: Legacy Edition is available at www.amazon.com

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024