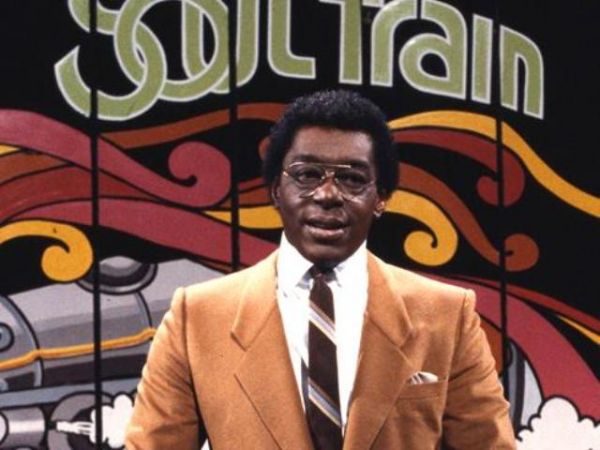

Don Cornelius (September 27, 1936-February 1, 2012): ‘When certain people started to walk through the door to appear, that's when I said I think we're going to make it’Crossing Over: Don Cornelius

'In Parting, We Wish You Love, Peace and Soul!'

On February 1 Los Angele police discovered the body of Soul Train creator-host-sine qua non Don Cornelius at about 4 a.m. at his Mulholland Drive residence in Los Angeles. He was taken to the hospital, where he was pronounced dead at 4:56 a.m., according to the coroner's office. A week later the coroner ruled Cornelius’s death a suicide by a self-inflicted gunshot to the head.

In syndication from 1971 to 2006, with Cornelius as its host from inception until 1993, Soul Train was an important national platform for R&B and soul acts—and for featured artists from other genres, such as the Native American-led Redbone—and for occasional social commentary on issues especially relevant to black Americans. James Brown, for one, appeared on Soul Train in a 1971 tribute during which he announced he was leaving the music business to concentrate on raising funds for and standards at black colleges, and Jesse Jackson was a welcome visitor as well.

The Soul Train Dancers, 'Theme from Shaft,' introduced by Don CorneliusSoul Train became even more important in the mid-1970s when radio consultants Lee Abrams and Kent Burkhart established the “Album-Oriented Rock” format that effectively eliminated black music from FM rock stations (and was stridently anti-disco). Cornelius refused to allow AOR to disenfranchise black artists from mainstream America’s popular culture, simply by staying on the air, increasing the number of stations syndicating Soul Train and putting the artists themselves on the nation's TV screens, most of them playing live and also engaging the host in conversation centered on serious topics relating to their careers and music.

Born Sept. 27, 1936, in Chicago, Cornelius worked as an insurance salesman before heading to broadcasting school in 1966. He also worked as a DJ and was a sports anchor for A Black's View of the News on WCIU in 1968.

A 1971 Soul Train tribute to James Brown, nearly ten minutes of priceless interview and performanceInspired by American Bandstand, Cornelius used $400 of his own money to create the pilot for Soul Train. He ended each episode with one of the most memorable signoffs in TV history: “And you can bet your last money, it's all gonna be a stone gas, honey! I'm Don Cornelius, and as always in parting, we wish you love, peace and soul!"

Cornelius told a judge during his 2009 divorce proceedings that he wanted to "finalize this divorce before I die." He was reportedly suffering from significant health issues. In a 2010 interview with the Los Angeles Times, Cornelius said he was in discussions with several people about developing a movie based on the show.

From October 2011, an interview with Don Cornelius

Don Cornelius interviews Mary Wilson of the Supremes and dances with her in the Soul Train Line

‘The Format Was An Idea Whose Time Had Come’

Don Cornelius Reflects on the Soul Train Years

(Editor's note: This is an edited version of a Q&A that was published in the Sun-Times on Sept. 3, 2010)

Why did Soul Train resonate with so many viewers?

The format was an idea whose time had come. Even though "Bandstand" had been around for a long time, there was nothing that kids in the music business who happened to be black got very excited about.

Was it difficult to get singers to do the show?

There were individuals at the time who were on the proverbial wish list, and before we had to wait too long, they decided to come in. Among the first were the Jackson 5. But we had to go after major people who were coming out of Chicago like the Chi-Lites and Curtis Mayfield. Jerry Butler helped me a lot in the early days to procure talent. Then Motown started to take notice and send people our way.

The Jackson 5 in their Soul Train debut, 1972, 'I Want You Back'Could you see something special in Michael Jackson even at such an early age?

You kinda couldn't miss it. He always had it. We were told he was eight years old when they appeared on our show, but we found out in recent years that he was actually 10. But even at 10, he was something special.

How do you define soul?

I don't know anybody who can define it. It's like trying to define hip-hop. You can't just call it black music. Maybe it will take a few more generations of music lovers to eventually define it.

There's great footage of Aretha Franklin performing. Did anybody do soul better than her?

She is and always will be the first lady of soul. There's nobody who ever did it like her.

Who was the greatest male soul singer, in your opinion?

Stevie [Wonder] is the epitome of soul.

Stevie Wonder, 'the epitome of soul' in Don Cornelius's estimation, performs 'Superstition' on Soul Train, 1971What was your favorite moment in the show's history?

Smokey Robinson and Aretha Franklin doing a duet on "Ooh, Baby Baby." And anything with James Brown playing live on our stage.

Why did you walk away from Soul Train?

A guy like me can't be doing "love, peace and soul!" shtick for the rest of his life until people start to say what's he doing that for? You gotta know when to get out. I loved it, but I just thought somebody younger should be doing it. And the mission got served. If your mission is to provide exposure and suddenly everybody is providing that same exposure, well, it's time to go.

Don Cornelius's favorite Soul Train moment: Smokey Robinson and Aretha Franklin in an exquisite duet on 'Ooo Baby Baby'.' It don't get better than this.Anybody you couldn't get no matter how hard you tried?

Nobody I'm willing to mention, but they know who they are.

Dancing on Soul Train to Redbone's 'Come and Get Your Love'

Don Cornelius Considers Soul Train at 40

‘We were becoming a guaranteed showcase for artists of our culture who didn't get that many offers to do national television, and we took that mission very, very seriously.’

Reached at home in Los Angeles, the notoriously tight-lipped Chicago native Don Cornelius opened up about Soul Train's early days, his feelings on hip-hop and why it was unwise to challenge Marvin Gaye to a game of hoops.

Does presenting the Soul Train 40th anniversary concert here in your hometown bring things full circle for you in some way?

It does, yeah, absolutely. It'll be good to come back and see some people that I haven't seen in a long time. And it'll probably be the last one in a while where people give me some applause for something I may have done.

From 1979: Aretha Franklin visits Soul Train and performs 'Mary Don't You Weep,' from her Amazing Grace albumChicago was very racially polarized when you were growing up on the South Side. What was your first exposure to racism?

I didn't really have that much. There were some neighborhoods a few blocks away that you couldn't go in because you might run into some violence that you weren't ready for. But as far as racism directly coming in my direction, not really.

Soul Train is best known for its music, but the show also featured appearances by political figures like the Rev. Jesse Jackson and (U.S. Rep.) Bobby Rush. What inspired you to reach outside the music sphere?

Well, those were my heroes, and I felt like we could help people like Bobby and Jesse get people's attention if we didn't overplay it. It was always part of our mission to support these guys that were trying to make things better.

Were you surprised when WCIU-TV offered you the chance to bring the show to television?

No, I wasn't surprised because I was invited to come over there by one of my mentors, Roy Wood, who was the news director at WVON-AM radio.

He was a good man. He had persuaded them to do a black-oriented news show called "A Black's View of the News." I knew the format at Channel 26 had a lot to do with ethnic-targeted programming, so I said to the owner one day, "Why don't you let me try this?"

A 13-minute segment of Al Green live on Soul Train, taking questions from the audience and performing Kris Kristofferson's 'For the Good Times' and his classic 'Love and Happiness'When you syndicated the program in 1971 only seven cities outside of Chicago purchased it, but by the end of the season you were on in 25 markets. At what point did you realize you had a success on your hands?

You know, I felt slightly encouraged, but I wanted 100 markets or 200 markets, and just ending up with eight markets was not knocking me out. I was gauging success by the kind of talent that had started to gravitate to the show--the Aretha Franklins, the James Browns, the Stevie Wonders. When certain people started to walk through the door to appear, that's when I said I think we're going to make it. We were becoming a guaranteed showcase for artists of our culture who didn't get that many offers to do national television, and we took that mission very, very seriously.

Do you feel like you gave hip-hop a fair shake when it was in its infancy? Has your opinion on the genre changed through the years?

I've been accused of not being up on hip-hop or not being a fan of hip-hop, which was never true. If you had a following and you were charting in the major industry magazines--Billboard, and before that Cash Box--we had a commitment that Soul Train was yours. And we lived up to that. We saw ourselves as a mirror of what black radio was doing. That whole criteria was part of what kept us going so long.

Marvin Gaye chats with Don Cornelius and fans, performs 'Let's Get It On,' Soul Train, 1974I found a video online of Marvin Gaye beating you one-on-one in basketball.

That was one of my worst decisions. I was sure I could beat him, you know?

Do you think you could have taken him if the cameras weren't there?

No. Marvin had a basketball court a few feet from his house and he played every single day. I looked like an idiot out there, and then tried to blame it on Smokey (Robinson). We recruited Smokey to be the ref, but there wasn't much reffing to do because I missed every shot I took.

(excerpt from an interview with Don Cornelius published in the Chicago Tribune, September 1, 2011)

'Love, peace and soul!'--Don Cornelius's timeless Soul Train sign-off

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024