This Land Is Their Land

In A Heartbeat and a Guitar: Johnny Cash and the Making of Bitter Tears, author Antonino D’Ambrosio explores a moment in time when Johnny Cash and Peter La Farge put the plight of Native People at the forefront of the folk boom of the ‘60s

By David McGee

When John F. Kennedy was elected President of the United States in 1960, Native American tribes were among his most fervent supporters. During the Eisenhower years, America’s Native people were helpless against a Republican-steered policy of “termination”—cutting off all Federal aid, services and protection for Native peoples living on reservations on the theory that the tribes should assimilate into the mainstream of American society. Utah Senator Arthur Watkins was the most vocal supporter of termination, claiming it would hasten the Native peoples’ progress towards self-determination. Opponents of the legislation—almost all of them from outside the government, with no power to sway opinion, public or otherwise—saw the termination program as yet another government land grab of tribal property so that states could initiate profitable public works projects, such as dams. On August 1, 1953, House Concurrent Resolution 108 (HCR-108) was adopted by Congress and inaugurated the era of termination in which Native American tribes lost all Federal recognition and legal protection with regard to culture, religion and land.

However, then-Senator Kennedy—who had supported the termination policy (as had Lyndon Johnson and Barry Goldwater)—sent a note to Pulitzer Prize winning author Oliver La Farge, president of the Association of the American Indian, promising, should he become President, a reversal of the termination program and a renewed commitment to action on behalf of the tribes’ interests in what would be a sharp break from an historical pattern, as Kennedy noted: “Indians have heard fine words and promises long enough. They are right in asking for deeds. The program to which my party has pledged itself will be a program of deeds, not merely of words.”

Further, Kennedy promised, “There will be no change in treaty and contractual relationships without the consent of the tribes concerned.”

Chief CorplanterShortly after assuming the office of the President on January 20, 1961, Kennedy not only reneged on his promise to the Native people, but also broke the oldest standing Indian treaty, one dating back to 1794 when George Washington had granted 15,000 acres along the Allegheny river in Pennsylvania to Seneca War Chief Cornplanter, his ancestors and five other Indian nations forever, in recognition of the Chief’s role in assisting in the protection of families settling in the wilderness of the upper Ohio River basin. In his 1790 Proclamation to Chief Cornplanter, President Washington noted: “Your great object seems to be the security of your remaining lands, and I have therefore, upon this point, meant to sufficiently strong and clear. That in the future you cannot be defrauded of your lands; that you possess the right to sell and the right to refuse to sell your lands.”

In one of the first acts of his Presidency, Kennedy, ignoring his own promises as well as those made and reaffirmed by all administrations after Washington’s, and oblivious to the protests of the Seneca tribe and its supporters, authorized the construction of the Kinzua Dam, which flooded the river and the Seneca reservation, forcing the tribe’s relocation to upper New York State, its home to this day. The tribal burial grounds were dug up and the remains (including those of Chief Cornplanter) were relocated to a nearby hillside. The Seneca still consider this a vile act of desecration, and insist as well that some tribal graves remain under the flooded Allegheny river.

In American Heritage Magazine, December 1968, Alvin M. Josephy, Jr. wrote, in part:

To the Senecas and to many other American Indians it was, moreover, another painful reminder that the history of white men’s injustices to them had not ended. Indian wars are no more, for the tribes’ power to resist with arms has vanished. But their defensive actions still go on, quietly now and with little or no publicity, in courts of law, and the Indians, more often than not, still continue to lose what they are defending. In their sadness they increasingly ask the white man: Why feel guilty and sorry about what happened in the nineteenth century? Pay closer attention to what you are still doing to us.

To the Senecas, the new body of water behind Kinzua Dam is known today as Lake Perfidy. And many a bitter Seneca tells his children and grandchildren that no one knows for sure whose bones lie beneath the transplanted monument above the lake: the way the moving took place, the remains could be those of another Indian from the old cemetery. The great Cornplanter, perhaps, now rests beneath the waters of the reservoir.

From the very beginning, when army lawyers first looked into the problem of acquiring land for the dam and the reservoir, the Corps of Engineers had little concern for the uniqueness of the treaty-secured Seneca position. The corps is a highly efficient and capable expression of the modern technological age, able to build great dams, move mountains, control roaring rivers, and alter any manner of landscape. But to many persons the corps exemplifies, at the same time, the big, self-propelled, faceless juggernauts of the world that grind ahead, seemingly unmoved by the outcries of the people whose lives they affect. As an autocratically tinged bureaucracy and one of the most irresistible lobbies in the nation (relying on the “pork barrel” support of political groups everywhere who sooner or later want public works for their own areas), it befriends the American people in the mass and in the abstract, and makes war on the same people when, as individuals or in small numbers, they get in the way.

Kinzua Dam: ‘To the Senecas and to many other American Indians it was, moreover, another painful reminder that the history of white men’s injustices to them had not ended.’This history has been largely lost on those who visit Kinzua Dam today. The website www.theallegheny.com/Kinzua_Dam touts the Dam as the “gateway to outdoor adventure,” and hails the building of it for having created “the state’s largest inland lake…and one of the nation’s best flat water canoeing rivers,” in addition to being the site of “record setting walleye and northern pike catches, as well as the state fishing tournament.” It also happens to have a well-documented history of numerous UFO sightings, further enhancing the weirdness of its history.

But scroll down towards the bottom of the website and lo, there is a link identified as “Johnny Cash Sings About Kinzua Dam.” Clicking on it reveals an embedded YouTube video of a gaunt Cash talking to Pete Seeger, with June Carter seated next to Seeger, about a promising young songwriter named Peter La Farge, who had contributed five songs to a new album of “Indian protest songs” Cash was recording, titled Bitter Tears. He begins a song he calls his favorite of all the La Farge songs, “As Long As The Grass Shall Grow.” A sample:

But on the Seneca Reservation

There is much sadness now

Washington’s treaty has been broken

And there is no hope no howAll across the Allegheny River

They’re throwing up a dam

It will flood the Indian country

A proud day for Uncle SamBut it broke that ancient treaty

With a politician’s grin

And will drown the Indian graveyards

Cornplanter, can you swim?

Johnny Cash sings Peter La Farge’s ‘As Long As The Grass Shall Grow, from the Bitter Tears album***

Born Oliver Albee La Farge, Jr. on April 30, 1931, raised in Colorado by his mother and stepfather, the son of Oliver La Farge Sr., whose Pulitzer Prize winning 1930 novel Laughing Boy was notable also for containing almost all Native American characters, grew up not wanting to be his father, not really sure what or who he wanted to be, in fact, and while still in school changed his name to “Pete” (later formalized to “Peter”) after a friend convinced hiim Oliver was a “sissy” name. He did, however, share his father’s passion for their common, albeit scant, Native American heritage as distant descendants of the Narragansett tribe.

Sickly as a child, Peter’s health improved when he was sent to Tuscon to attend school, and there he began a lifelong pattern of moving from one obsession to another, trying to find something that held his attention. Poetry, painting, boxing were fleeting interests, but he did take seriously to bronco riding, and soon was competing in rodeos throughout the southwest. Still restless, he dropped out of high school and enlisted in the Navy at age 18,. According to his sister Povy Bigbee, Pete’s enlistment saved him from graduating—he had lost interest in school (“I use the term student loosely,” she says). In the Navy he became an undercover antinarcotics operative for its Central Intelligence division; his sister claims he never turned in his fellow servicemen, but Peter himself claimed he was “very successful at what I did, but it cracked me up. One of the most difficult things to do in the world is to betray your fellow man.” When a plane crashed on an aircraft carrier and ignited stored ammunition, La Farge was severely burned and lost some hearing in his left ear. He was through with the Navy; returning to civilian life, he signed on with the rodeo again, only to have a leg injury end his career. He then migrated to Chicago to study acting at the Goodman Theater School of Drama. He was not merely tweaking his autobiography at this point; he was literally making one up. When he moved to New York City and landed a role in a play, his self-penned program bio claimed he had been “a concert folksinger since the age of fourteen.” As author Antonino D'Ambrosio notes in A Heartbeat and a Guitar: Johnny Cash and the Making of Bitter Tears (Nation Books, 2009), his detailed examination not only of a near-forgotten Johnny Cash album devoted to Native American issues and stories but also to the intersect of folk music, politics, civil rights, Native American rights, history and music business shenanigans in the early ‘60s, creating a new personal history was practically a noble tradition in the arts, and especially in music—witness Brooklyn-born Elliott Charles Adnopoz self-styling himself a cowboy and folksinger and befriending Woody Guthrie as Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, for one. Witness Johnny Cash, for another, claiming Cherokee descent, only to come clean years later as having no Indian blood whatsoever in his family line.

La Farge, as D’Ambrosio documents, had a marvelous talent for self-invention, as his many pre-folksinger incarnations indicate. When he dove into the music world, though, he did so with full vigor and commitment. Cisco Houston took La Farge under his wing, mentored him in songwriting and championed him in the bustling Greenwich Village folk scene. Josh White, an outcast among the left leaning folkies for having cooperated with the House Un-American Activities Committee, became his guitar teacher. The politically charged atmosphere of the Village inspired La Farge, who, taking note of the burgeoning Civil Rights movement, figured a similar focus on the plight of Native people could only help improve his people’s lot as well.

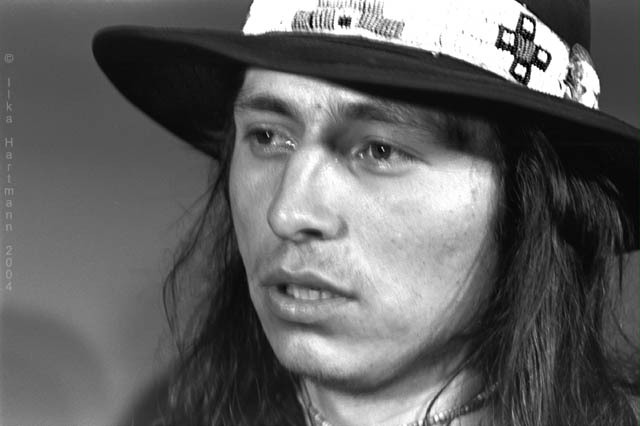

Native activist/musician John Trudell: 'Native people could not have a civil rights movement. The civil rights issue was between the Blacks and the whites but I never viewed our cause as a civil rights issue for us. They’ve been trying to trick us into accepting civil rights but America has a legal responsibility to fulfill those treaty law agreements.’ (Photo: Ilka Hartman)Native Americans, though, were organizing outside the Civil Rights movement proper. D’Ambrosio notes how Native people declined to participate in 1963’s March on Washington. Native activist/musician John Trudell explains, “Native people could not have a civil rights movement. The civil rights issue was between the Blacks and the whites but I never viewed our cause as a civil rights issue for us. They’ve been trying to trick us into accepting civil rights but America has a legal responsibility to fulfill those treaty law agreements. If you’re looking at civil rights, you’re basically saying, ‘Alright, treat us like the way you treat the rest of your citizens—I don’t look at that as a climb up [in U.S. society].”

Buffy Sainte-Marie, ‘Universal Soldier’

La Farge, with so little Native American blood in him he had almost run out, took the tribes’ plight as his cause. Not long after he arrived in Greenwich Village, 21-year-old Buffy Sainte-Marie showed up as the real deal: a Native from the Piapor Cree Indian Reserve in the Qu’Appelle Valley in Saskatchewan, Canada. Her songwriting was greatly advanced for one so young, and two of her topical numbers, “Universal Soldier” (which does nothing less than illustrate the madness of war throughout history, and exempts no one from responsiblity) and “Cod’ine” (a searing depiction of the horrors of drug addiction), earned her near-instant acclaim, including a favorable review by New York Times critic Robert Shelton, who was also the first to weigh in on the promise of one Bob Dylan. A mutual admiration society formed between Sainte-Marie and La Farge, the former admiring La Farge’s commitment to Native causes, the latter smitten with Sainte-Marie on multiple levels, most especially as a courageous voice on behalf of Native people.

While La Farge was making his bones in Village clubs, Johnny Cash was on his own trajectory. Having left Sun Records in 1958 for Columbia Records and a promise of greater control over his recordings, Cash had issued a rarity in the form of a country concept album of train songs, Ride This Train, and an album of narration over a recording of Grofé’s Grand Canyon Suite, titled Lure of the Grand Canyon. His stature in the country music field was growing exponentially, he was becoming more daring in his recording choices, and in May 1962 he was on the precipice of major national acclaim when he arrived in New York City for a concert at Carnegie Hall. He was also in personal disarray: his voice was shot, and an over-reliance on Dexedrine diet pills had produced a frightening weight loss. Freaked out about appearing at one of the world’s most prestigious concert halls, Cash arrived late for the show, disheveled (“He looked like he had just hopped on a freight train after taking it all the way across the country to get there for the show,” says his bass player, Marshall Grant) and, in D’Ambrosio’s words, “frenzied and agitated.” The set, which was supposed to consist entirely of Jimmie Rodgers songs in tribute to the father of modern country music, was a disaster. When Cash opened his mouth to sing, no sound came out. He fell to the stage floor attempting to play his guitar and crawled around on his knees trying to strum it. He knocked over a microphone and sent feedback howling throughout the auditorium. After about half an hour of floundering, he left the stage— to polite applause, according to the author.

With a few days off following the Carnegie Hall debacle, Cash stayed in Manhattan, hanging out with Ed McCurdy, one of the veterans of the Greenwich Village folk scene, with a decade of experience under his belt at that point. McCurdy suggested he and Cash wander down to the Gaslight Café to hear what was going on. Sitting at the bar and chatting with McCurdy, Cash’s attention was suddenly drawn to the stage, to the young folksinger who was ardently singing Indian protest ballads, including one he had written titled “The Ballad of Ira Hayes.” Later in the week, McCurdy brought La Farge with him to Cash’s hotel and suggested they all go down to the Village together to check out some music. Cash was all for it, as long as he could pop some Dexedrine first; over McCurdy’s protests he did so, and La Farge joined him. Pills or no, Cash was entranced by La Farge’s “Ira Hayes” song detailing the tragic life of its titular character, a World War II hero (he’s the last in the line of Marines raising the flag at Iwo Jima in the famous staged photo) from Arizona’s Pima tribe who had returned to his country to considerably less than a hero’s welcome, found no work, became something of a freak sideshow at events and rallies that wanted to exploit his fame, and finally descended into the depths of alcoholism. He died drunk and forgotten in a ditch.

The Ira Hayes story connected with Cash’s own history. Like Hayes, Cash had joined the military both to escape the poverty of his upbringing and to create a new life for himself and his family. What alcohol was to Hayes—his undoing and destruction—was what pills were threatening to become for Cash. After learning more about Hayes, Cash traveled to Arizona to visit with Hayes’s family. Ira’s mother presented him with a translucent stone of volcanic black glass, called an “Apache tear.” She explained its name as stemming from the last U.S. cavalry attack on Native people, when troops massacred Apaches in Arizona much as they had at Wounded Knee. Following the slaughter, the cavalry soldiers refused to allow the Apache women to observe a sacred Apache tradition of mounting their dead on stilts. Legend has it that the Apache women’s tears, upon falling earthward, turned the ground around them black. Cash polished the stone and mounted it on a gold chain around his neck.

“The Ballad of Ira Hayes” made Pete La Farge a rising star of the folk scene. In a home movie shot at Alan Lomax’s apartment, La Farge stands out in a crowd that included Memphis Slim and Willie Dixon, Clarence Ashley and Doc Boggs, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Jean Ritchie, the New Lost City Ramblers and Roscoe Holcomb. Seizing his moment, he performed a version of “The Ballad of Ira Hayes” that had Elliott agog: “La Farge just brought this incredible intensity when he performed,” Elliott told D’Ambrosio. “He had this poetry that is ‘Ira Hayes’—you couldn’t help but be riveted and moved.”

Seeing La Farge playing the guitar almost violently, nearly spitting the words out as he looks into the camera, one senses that he not only believed every word but that he somehow lived the terrible story every time he sang it. The image created by just the sounds of Lomax’s raw, unedited audio recording of La Farge’s performance is even more powerful because the anguish and fury in his voice create a searing image in one’s imagination. The words ring true as La Farge hands down an indictment, a scorched-earth, take-no-prisoners telling from a point of view that is often unwelcome and concealed. (D’Ambrosio, p. 104)

Legendary Columbia Records A&R director John Hammond snapped up La Farge a few months before signing one of La Farge’s Village buddies, Bob Dylan. On August 25, 1960, Hammond took La Farge into the studio and produced his debut album, “Ira Hayes” and Other Ballads. Well received critically upon its release in 1962, the long player led La Farge to a triumphant concert at Town Hall, the repertoire of which now included his condemnation of the Kinzua Dam project in the seething, bitter “As Long As The Grass Show Grow.”

The roller-coaster that was Pete La Farge’s life was grinding ceaselessly up steep ascents and plunging rapidly into perilous drops. Columbia cut him loose after one album, but Moses Asch of the venerated Folkways label signed him and cut five albums with La Farge between 1962 and 1965, all heavy on Native American themes but also branching out into other topical fare. His erratic behavior—distant and troubled by some estimations, good-natured and laid back by others—began to alienate his friends in the folk community. His drug use and drinking escalated to alarming proportions and seemed to affect the quality of his writing. His passion for Native American issues was not shared wholeheartedly by his peers, who addressed “sexier” issues in their topical songs—Civil Rights,and the expanding war in Vietnam; ultimately, La Farge and Sainte-Marie were left alone to carry the banner for Native people.

“The folk community had ambivalent feelings about Peter,” D’Ambrosio quotes writer/musician/activist Julius Lester. “He did not have the greatest voice, nor did he have a lot of showmanship on stage. He wasn’t polished. What he did have was a ‘sincerity.’ He was real. I think we both felt kind of like outsiders in the folk music world because we may have been more serious, a little more sincere about the things we were singing about. Protest music was not a ‘career’ move for Peter; it was what he believed in.”

If Cash related to Ira Hayes, he most certainly forged an immediate connection with La Farge. D’Ambrosio reports how Cash instructed La Farge in the nuances of the Dexedrine and Thorazine pills they were gobbling, “the latter to help with coming down from the former.” Under the influence, La Farge would sleep for nearly four days, which initially worried his friends, although folk singer Oscar Brand tells the author, “(Pete) could zonk out faster and harder than anyone I ever met and wake up three or four days later.”

Though battling his own addiction, Cash was ready and focused when he assembled his band (along with guitarist Al Casey and dobro master Norman Blake) for what he vowed would be an album of “Indian protest songs.” So it was: its hard hitting eight tracks included La Farge’s “The Ballad of Ira Hayes,” “As Long as the Grass Shall Grow,” “Custer,” “Drums” and “White Girl,” plus Cash’s own “Apache Tears” (inspired by the story Ira Hayes’s mother had told him about the last massacre) and, closing out side one, “Talking Leaves,” with side two, and the album, signing off with Cash and Johnny Horton’s haunting co-write, “The Vanishing Race.” Cash wanted one other person around for the sessions, too—Peter La Farge, who flew into Nashville with Ramblin’ Jack Elliott at his side.

Oscar Brand says Cash and La Farge were outsider peas in a pod, their differences making them all the more similar to one another. “The two of them together made a remarkable pair,” he told D’Ambrosio. “One of them was doing an actor’s job on being an outlaw and the other doing a job of being a real Indian. To me, in some ways they were like cartoons in a book. With all their differences, there was something the same, It was a feeling that they have been hustled out of the crowd and turned out the door at the good party. They were considered not wanted—who wanted a poor guy from Arkansas, or a troubled kid from the Southwest? You can throw Dylan in there, too, a guy writing new songs imitating Woody Guthrie.”

Cash’s version of “The Ballad of Ira Hayes” was dramatic, direct, raw and combustible, his gravely voice rising up in barely contained outrage when he hit the final verse and rose in sarcastic exultation at the closing chorus:

Then Ira started drinkin’ hard

Jail was often his home

They’d let him raise the flag and lower it

Like you’d throw a dog a bone.He died drunk one mornin’

Alone in the land he fought to save

Two inches of water in a lonely ditch

Was a grave for Ira Hayes.(Chorus)

Yeah, call him drunken Ira Hayes

He won’t answer anymore,

Not the whiskey drinkin’ Indian

Nor the Marine that went to war.

Titled Bitter Tears (subtitled Ballads of the American Indian), the album featured a cover head shot of a grim featured, raccoon-eyed Cash, a bandana around his head, one skinny arm raised above his eyes to block the sun from his emaciated features. His high hopes for its success were dashed immediately: the lead single, “The Ballad of Ira Hayes,” bombed—speculation was rife that its four-minutes-plus length undercut its appeal to radio programmers; others speculated along the lines of the Columbia executive who opined as to how disc jockeys were looking for Cash to ”entertain, not educate.”

With radio effectively embargoing the album, Columbia crumbled and refused to promote it. Billboard refused to review it. An editor at a country music magazine insisted Cash should resign from the Country Music Association because “you and our crowd are just too intelligent to associate with plain country folks, country artists and country DJs.” In a meeting with two powerful disc jockeys, Johnny Western, an actor/singer/radio host who was part of the Cash touring troupe at that time, was told by one that the music on Bitter Tears was un-American and that not only would he not play the record on the air, he would politic other DJs and stations to do the same. “Just ignore it until John came back to his senses, is what he told me,” Western says.

Cash responded to this censoring of his work by writing a letter to the music business at large and placing it as a full-page ad in Billboard's August 22, 1964 issue. “Where are your guts?” he demanded, and even suggested the charge of it being too much of the truth was correct. “Teenage girls and Beatle record buyers don’t want to hear this sad story of Ira Hayes. This song is not of an unsung hero… This is not a country song, not as it is being sold. It is a fine reason for the gutless to give it a thumbs down.”

He added in closing: “’Ira Hayes’ is strong medicine. So is Rochester, Harlem, Birmingham and Vietnam.”

In the end Cash triumphed: the “Ira Hayes” single peaked at #3 on the country charts, and Bitter Tears soared to #2 on the album chart. Though his drug addiction and erratic behavior had become too much for his wife, Vivian, and she had requested he leave her and their four daughters, he remained amazingly prolific in the studio, following Bitter Tears with his Orange Blossom Special album, featuring songs by Bob Dylan, and following that with another concept album, Johnny Cash Sings the Ballads of the True West.

Back in New York, La Farge was trying to get his life together, too. He had penned an effusive review of Bitter Tears for Sing Out! (“Driven, complicated, and expert, Johnny Cash is a great American voice.”) He and Cash both had played the New York Folk Festival to great acclaim in 1965, with Cash’s Carnegie Hall performances erasing memories of the 1962 disaster. In fact, the Times’s Robert Shelton—who had given the ’62 show a respectful review despite Cash’s addled antics—lauded “Mr. Cash’s stage manner, one of constant movement” and likened it to “a graceful matador in the ring.” It “keeps his performances cracking with visual interest,” Shelton opined.

While Cash could obviously get it together to put on a stirring live show, and could bring it in the studio when he finally buckled down, he was otherwise, in D’Ambrosio’s account, “pouring pills down his throat like water. Soon there were car accidents, missed performances and cancelled shows.” Finally, upon returning from a trip to Juarez, he was arrested after Customs agents found his guitar case stuffed with pills and tranquilizers. He spent a night in county jail, pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor charge, paid a thousand dollar fine and received a 30-day suspended sentence.

La Farge, on the other hand, had met and married Inger Nielsen, a Danish singer, and the couple were preparing for the birth of their first child. Having returned to an earlier love, painting, he had even sold one of his works. He was formulating plans for two books, one about his experiences in the Korean War, the other an autobiography. Diagnosed as schizophrenic, he opted for experimental treatments of cobra venom, which was then believed to be effective in combatting various mental illnesses. He and his sister spoke regularly by phone; she urged him to come back to Arizona, and he indicated he would.

When Inger returned to their apartment on East 50th Street on October 27, 1965, she found Peter unconscious. By the time an ambulance arrived, he was dead. Wild stories began circulating that La Farge had committed suicide, or had expired from a stroke or heart attack or drug overdose, or maybe that the FBI was somehow involved in exterminating him. Cause of death was never determined—in keeping with the family’s Baha’i religious beliefs, there was no autopsy. But his sister Povy remains certain her brother did not commit suicide. “When I saw the body, he looked so peaceful. He even had a knee up with a smile on his face and his ankle crossed over like he was about to read something. And that’s how Inger found him. I feel that in his attempt to deal with his mental illness, he took another dose of cobra venom and it hit his heart and paralyzed it. That’s how he died. Buy I can’t prove it.”

After confirming his lack of Cherokee heritage, Cash remained strong in his support of Native American causes, and also spoke out against the war in Vietnam and addressed other social issues. Four years after the release of Bitter Tears he performed the album at Wounded Knee; one of the tribal chiefs later told him of a vision “that you would come here and sing this song for us,” which nearly moved Cash to tears. Querying a friend about the facts of the Wounded Knee massacre as they rode back to the airport, he took notes. By the time they arrived at the airport, he had composed one of his greatest Indian ballads, “Big Foot,” a tribute to the chief of the Miniconjou Lakota Sioux who was killed during the massacre.

Marshall Grant notes that Cash “never stopped playing songs off Bitter Tears,” and Johnny Western adds: “Peter La Farge and that experience had a long, profound effect on Cash.”

Through one short lasting encounter, La Farge and Cash had come together, allied as men searching for themselves and musicians hoping to connect with the world outside. “As far as our generation goes,” says John Trudell, “to my knowledge, La Farge was the first one to address grave Native issues as an artist, musically speaking. He became the first so-called protest songwriter for Native people, but his writing became that voice. He wasn’t limited to that; he also did things like ‘Radioactive Eskimo,’ in addition to the music people are more familiar with like ‘Ira Hayes’ and ‘As Long as the Grass Shall Grow.’” (D’Ambrosio, p. 217)

D’Ambrosio, author of Let Fury Have the Hour: The Punk Rock Politics of Joe Strummer, diligently recreates the fertile world of folk music in the ‘50s and early ‘60s that produced Peter La Farge. Names such as folk singer Ed McCurdy, Oscar Brand, the Highlander Folk Center and Guy Carawan—even, to a certain extent, Buffy Sainte-Marie—are rarely if ever mentioned anymore, but all, and more, played important roles in igniting the folk boom and pushing its activist agenda. To that end, the music could not be separated from the political and social issues of the day, and so the intersect between the Civil Rights movement and the folk movement is given thorough scrutiny even as the author retraces La Farge's peripatetic life—witness how Cash, purportedly the subject of the book, is but a fleeting presence in the narrative until almost the halfway mark of the 296-page text. His account of the signal moment in La Farge’s artistic life—the breaking of the treaty that allowed the Kinzua Dam to be built on Seneca land—is especially well drawn, thoroughly researched and written with barely suppressed rage, as is proper. Also, far more effectively than David Hadju in Positively Fourth Street, or even Dylan in his own superb Chronicles, D’Ambrosio’s account of the link between folk music and the hot-button issues of the late ‘50s and early ‘60s underscores the level of genuine commitment the folk artists of that time had to the notion of effecting social change via art and activism working in concert, spurred on by the examples set earlier in history by Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie. It’s impossible to read A Heartbeat and a Guitar and not lament the lack of such commitment in today’s mainstream music, when too many artists exploit a cause for their own aggrandizement, or address it once and move on in pursuit of fame and fortune. Oh, what a time it was, indeed.

However, in the age of Google, the book is shot through with factual errors and misspellings that could have been easily checked. It’s been a long time since Lead Belly’s name has been published as Leadbelly, given the family’s insistence in the early ‘90s that the former is the correct appellation; Cash’s long-time drummer, W.S. “Fluke” Holland, did not “sit in” on the so-called Million Dollar Quartet session at the Sun Studio on December 4, 1956, with Elvis, Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis and Carl Perkins—he was the drummer in Perkins’s band and was in the midst of one of Carl’s most productive Sun sessions (it yielded the Perkins classic, “Matchbox,” later covered by The Beatles, and one of the finest of Perkins’s bopping, countrified ditties, “Your True Love”) when Elvis walked in fresh from his first (and poorly received) Las Vegas appearance and brought everything to a halt. D’Ambrosio’s account makes it sound like Cash hired Holland on the spot after the Million Dollar Quartet session when in fact Holland worked with Perkins into 1959, then left to become Sun artist Carl Mann’s manager; when that failed to pan out, he was preparing to abandon music entirely and take a job with the city of Jackson, TN, when Cash called in 1961 and asked him to join his band. Cash's onstage introduction of Holland thereafter as "the first rock 'n' roll drummer" was a reference to Fluke's tenure with what was billed as The Perkins Brothers Band in the honky tonks in and around Jackson, TN, where he joined Carl and his brothers Jay and Clayton in advancing a fresh, thumping, stomping new hybrid music Carl had shaped out of country, pop and rhythm and blues influences that would later be dubbed Rockabilly. Garry Wills’s name is misspelled as Gary; the Alabama town that was the site of a hoped-for meeting on racial equality (with Paul Newman and Marlon Brando, among others, slated to attend) is Gadsden, not Gadson.

Jolting as they are, these are mostly niggling errors, bespeaking a certain sloppiness by author and editor both. In the end, the story D’Ambrosio tells is of far greater import than an earlier book on Cash’s Folsom Prison album (Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison: The Making of a Masterpiece) and boasts an historical sweep—the specifics of which he does seem to have thoroughly researched—few other artists’ stories, whether those be life stories or a chapter of life, as this one is, can match. Tragic as his life was, Peter La Farge taught Cash something important about America and about Johnny Cash. The Man in Black never forgot, and so honored the memory of his fallen friend to the end of his days. Antonino D’Ambrosio has done a laudable job in his own right of insuring proper recognition of Peter La Farge, and not least of all, of reminding us of how our Native people await proper recognition in this land that is their land.

Click here for an interview with author Antonino D’Ambrosio.

In this month’s VIDEO FILE, Johnny Cash performs the entire Bitter Tears album.

***

On Stage, Here and There

SETLIST: THE VERY BEST OF JOHNNY CASH

Legacy RecordingsBeyond A Heartbeat and a Guitar there is even newer Johnny Cash fare for the dedicated fan, completist and casual alike. Legacy’s live Setlist series has issued 14 choice cuts from the extensive catalogue of Cash concert recordings as The Best of Johnny Cash Live. Though the songs are familiar, their sources are less obvious, coming, in some instances, from the unabridged editions of Cash’s concerts at Folsom Prison and San Quentin issued in box sets, and from new concert fare from a Madison Square Garden concert in 1969, and a Best of The Johnny Cash TV Show collection. Three cuts, in fact, are from one of the most rare of all Cash items, a live album available by import only (Pä Österåker), recorded in 1972 at Österåker Prison, in Sweden, near Stockholm, and issued overseas in 1973. These cuts include a touching rendition of Gene Autry’s “That Silver-Haired Daddy of Mine,” which Cash dedicates to his own then-75-year-old father in a version further enhanced by the sensitive, melodic guitar support of Carl Perkins; a measured treatment of “Life Of a Prisoner,” a frank account of the inmate’s day to day experiences and feelings written by an inmate at a U.S. prison farm, Jimmy Wilkerson; and a blazing hot romp through “A Boy Named Sue,” taken at such a pace that Cash sounds like he’s got all he can handle keeping up with the band—an exhilarating performance that’s less vinegary and more intense than the famous one from San Quentin. From the 1969 Madison Square Garden performance comes one of Cash’s most beautiful and sorrowful numbers, “I Still Miss Someone,” exquisitely rendered. The entire Cash troupe—the Carter Family, the Statler Brothers and Perkins (singing this time)—get into the act on a live cut from Denmark in 1971, when those assembled wreck the house with a foot stomping, hand clapping gospel celebration on “Children, Go Where I Send Thee.” Johnny and June Carter, one of country music’s greatest duet pairings, show why that is so in scorching Ray Charles’s “I Got a Woman” at Folsom Prison, and from a show at the Ryman Auditorium in 1969, kicking up their heels on a trio of songs they trademarked in duet form—John Sebastian’s “Darlin’ Companion,” Tim Hardin’s “If I Were a Carpenter,” and their monument, Jerry Leiber-Billy Edd Wheeler’s “Jackson.” Cash’s stately reading of “The Wreck of the Old 97,” from San Quentin, ranks with his finest story-song performances. Not the least of this Setlist’s virtues is a matter-of-fact version of “What Is Truth,” from a White House performance for Richard Nixon on April 17, 1970. Nixon had requested “Welfare Cadillac,” and instead the Man in Black presented him with a blunt and sympathetic look at the counterculture’s questioning of the status quo Nixon sought to protect by any means necessary. As an overview of what Johnny Cash could achieve onstage at a critical juncture of his career (the 14 songs represent the years 1968 to 1972), Setlist: The Very Best of Johnny Cash Live is a powerful document indeed. –David McGee

Setlist: The Very Best of Johnny Cash Live is available at www.amazon.com

Johnny Cash performs Kris Kristofferson’s ‘Help Me Make It Through the Night’ at Sweden’s Österåker Prison, 1972.

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024