L. Frank Baum: Racist

Indian-Hating in The Wizard of Oz

By Thomas St. John

(Published in Counterpunch, http://www.counterpunch.org/stjohn06262004.html Weekend Edition / June 26/27, 2004)

Lyman Frank Baum (1856-1919) advocated the extermination of the American Indian in his 1899 fantasy The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Baum was an Irish nationalist newspaper editor, a former resident of Aberdeen in the old Dakota Indian territory. His sympathies with the village pioneers caused him to invent the Oz fantasy to justify extermination. All of Baum's "innocent" symbols clearly represent easily recognizable frontier landmarks, political realities, and peoples. These symbols were presented to frontier children, to prepare them for their racially violent future.

The Yellow Brick Road represents the yellow brick gold at the end of the Bozeman Road to the Montana gold fields. Chief Red Cloud had forced the razing of several posts, including Fort Phil Kearney, and had forced the signing of the Fort Laramie Treaty. When George Armstrong Custer cut "the Thieves' Road" during his 1874 gold expedition invasion of the sacred Black Hills, he violated this treaty, and turned U.S. foreign policy toward the Little Big Horn and the Wounded Knee massacre.

The Winged Monkeys are the Irish Baum's satire on the old Northwest Mounted Police, who were modeled on the Irish Constabulary. The scarlet tunic of the Mounties, and the distinctive "pillbox" forage cap with the narrow visor and strap are seen clearly in the color plate in the 1900 first edition of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Villagers across the Dakota territory heartily despised these British police, especially after 1877, when Sitting Bull retreated across the border and into their protection after killing Custer.

The Shifting Sands, the Deadly Desert, the Great Sandy Waste, and the Impassable Desert are Frank Baum's reference to that area of the frontier known always as "the great American desert," west and south of the Great Lakes. Baum creates these fictional, barren areas as protective buffers for his Oz utopia, against hostile, foreign people. This "buffer state" practice had been part of U.S. foreign policy against the Indians, since the earliest colonial days.

The Emerald City of Oz recreates the Irish nationalist's vision of the Emerald Isle, the sacred land, Ireland, set in this American desert like the sacred Paha Sapa of the Lakota people, these mineral-rich Black Hills floored by coal. Irish settlements in the territories, in Kansas, Nebraska, and Minnesota—at Brule City, Limerick, at Lalla Rookh, and at O'Neill two hundred miles south of Aberdeen—founded invasions of the Black Hills.

The Yellow Winkies, slaves, are Frank Baum's symbol for the sizable Chinese population in the old West, emigrated for the Union-Pacific railroad, creatures with the slant or winking eyes.

The Deadly Poppy Field is the innocent child's first sight of opium, that anodyne of choice for pain in the nineteenth century, sold in patent medicines, in the Wizard Oil, at the traveling Indian medicine shows. Baum's deadly poppies are the poison opium, causing sleep and the fatal dream.

Photo:wickedwitchwest1900.jpg(inset)

The Wicked Witch of the West is illustrated in the 1900 first edition as a pickaninny, with beribboned, braided pigtails extended comically. Baum repeats the word "brown" in describing her. But this symbol's real historic depth lies in the earlier Puritans' confounding of European witches with the equally heathen American Indians.

The orphan Dorothy's violent removal from Kansas civilization, her search for secret and magical cures for her friends, her capture, enslavement to an evil figure—and the killing of this figure that is forced on her—all these themes Baum takes from the already two hundred year old tradition of the Indian captivity narrative which stoked the fires of Indian-hating and its hope of "redemption through violence."

In the year immediately following the huge success of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Baum wrote a fantasy entitled The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus. It is apparent that his frontier experiences were still on his mind. The book was illustrated by Mary Cowles Clark—tomahawks, spears, the hide-covered teepees, and the faces of Indian men, women, and children, and papooses fill the pages and the margins. Baum describes the "rude tent of skins on a broad plain."

Two crucial chapters are titled "The Wickedness of the Awgwas" and "The Great Battle Between Good and Evil." The Awgwas represent Native Americans: "that terrible race of creatures" and "the wicked tribe." Baum condemns the Awgwas:

"You are a transient race, passing from life into nothingness. We, who live forever, pity but despise you. On earth you are scorned by all, and in Heaven you have no place! Even the mortals, after their earth life, enter another existence for all time, and so are your superiors."

Predictably enough, a few pages later, "all that remained of the wicked Awgwas was a great number of earthen hillocks dotting the plain." Baum is recalling newspaper photos of the burial field at Wounded Knee.

(Ed. Note: Read the entire book online at http://www.pagebypagebooks.com/L_Frank_Baum/The_Life_and_Adventures_of_Santa_Claus/. It’s a real stretch to make the leap from Awgwas to Native Americans.)

The Wizard of Oz in 1899 ruling his empire from behind his Barrier of Invisibility evokes the 1869 Imperial Wizard of the Invisible Empire of the South, the Ku Klux Klan. Baum's figure King Crow and his by-play with the Scarecrow relate to the Jim Crow lynch law at the turn of the century.

Lyman Frank Baum's overwhelmingly popular fantasy, and the more violent aspects of United States foreign policy, were welded together in the American mind for the next century and beyond. Frank Baum's widow, at the Hollywood premiere of The Wizard of Oz in 1939, complained that the story had been sentimentalized. Indeed, the old and crudely direct political symbols had been removed, and the sweetness poured in—the new U.S. foreign policy demanded more subtle justifications.

"Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it."

Thomas St. John graduated from Drew University in Madison, New Jersey, and lived in Boston and Cambridge, Massachusetts. He is the author of Forgotten Dreams: Ritual in American Popular Art (New York: The Vantage Press, 1987), a collection of essays on Nathaniel Hawthorne's The House of the Seven Gables, Reverend Jonathan Edwards' "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God," the black history driving the films Casablanca and the cartoon "The Three Little Pigs," and the Dakota Indian territory symbols in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. The short book Nathaniel Hawthorne: Studies in the House of the Seven Gables is now almost complete and online.

L. Frank Baum on Native Americans: The Editorials

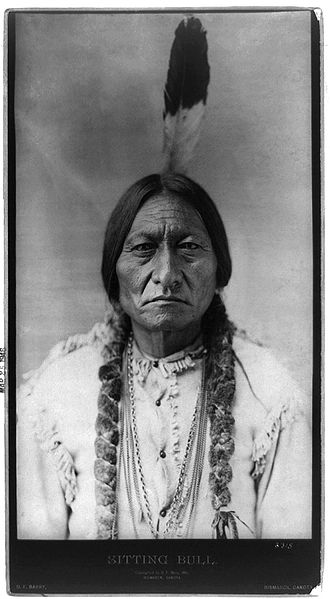

I. Upon Sitting Bull’s Death

Upon hearing of the death of the Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux holy man Sitting Bull, Baum wrote an editorial for the Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer. It was published on December 20, 1890, five days after the Chief was killed while being arrested by police officers at the Standing Rock Agency in South Dakota. Baum's point here, misguided though it was, centered on his assessment of the remaining Native Americans as being inferior to the noble tribes of their ancestors. Sitting Bull he judged to be the last of a breed, and those left, being bereft of glory, spirit and strength, unworthy of surviving him.

Sitting Bull, most renowned Sioux of modern history, is dead.

He was not a Chief, but without Kingly lineage he arose from a lowly position to the greatest Medicine Man of his time, by virtue of his shrewdness and daring.

He was an Indian with a white man's spirit of hatred and revenge for those who had wronged him and his. In his day he saw his son and his tribe gradually driven from their possessions: forced to give up their old hunting grounds and espouse the hard working and uncongenial avocations of the whites. And these, his conquerors, were marked in their dealings with his people by selfishness, falsehood and treachery. What wonder that his wild nature, untamed by years of subjection, should still revolt? What wonder that a fiery rage still burned within his breast and that he should seek every opportunity of obtaining vengeance upon his natural enemies.

The proud spirit of the original owners of these vast prairies inherited through centuries of fierce and bloody wars for their possession, lingered last in the bosom of Sitting Bull. With his fall the nobility of the Redskin is extinguished, and what few are left are a pack of whining curs who lick the hand that smites them. The Whites, by law of conquest, by justice of civilization, are masters of the American continent, and the best safety of the frontier settlements will be secured by the total annihilation of the few remaining Indians. Why not annihilation? Their glory has fled, their spirit broken, their manhood effaced; better that they die than live the miserable wretches that they are. History would forget these latter despicable beings, and speak, in latter ages of the glory of these grand Kings of forest and plain that Cooper loved to heroise.

We cannot honestly regret their extermination, but we at least do justice to the manly characteristics possessed, according to their lights and education, by the early Redskins of America.

II. Upon News of The Wounded Knee Massacre

Following the December 29, 1890 massacre at Wounded Knee, Baum wrote another editorial, published on Jan. 3, 1891, in which he advocated the extermination of Native Americans.

The peculiar policy of the government in employing so weak and vacillating a person as General Miles to look after the uneasy Indians, has resulted in a terrible loss of blood to our soldiers, and a battle which, at best, is a disgrace to the war department.

There has been plenty of time for prompt and decisive measures, the employment of which would have prevented this disaster.

The Pionner has before declared that our only safety depends upon the total extermination of the Indians.

Having wronged them for centuries we had better, in order to protect our civilization, follow it up by one or more wrong and wipe these untamed and untamable creatures from the face of the earth.

In this lies safety for our settlers and the soldiers who are under incompetent commands.

Otherwise, we may expect future years to be as full of trouble with the redskins as those have been in the past.

An eastern contemporary, with a grain of wisdom in its wit, says that “when the whites win a fight, it is a victory, and when the Indians win it, it is a massacre."

Discounting the far-fetched interpretation of The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus above, these are the only known occasions when Baum published his opinions of Native Americans. In his short story "Aunt Jane's Nieces and Uncle John," he sides with the tribes in criticizing the sad state of Indian Reservations, although his white characters are portrayed as being disgusted by the Hopi snake dance. In 2006, Baum descendants issued an apology to the Sioux Nation for any harm his statements may have caused.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024