Setting ‘Oz’ To Music, and Going Over the Rainbow: The Art of Harold Arlen & Yip Harburg

(or, How ‘Somewhere Over the Rainbow’ Was Saved from the Cutting Room Floor)

by Aljean Harmetz

(Ed. Note: In her essential inside look at the business and artistry of The Wizard of Oz, The Making of the Wizard of Oz, noted film critic Ajean Harmetz chronicled the creative musical collaboration of composers Harold Arlen and E.Y. “Yip” Harburg, including the revelation that their most famous song, “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” was cut from the film by MGM studio boss L.B. Mayer following the first preview. Now out of print, Harmetz’s book remains the definitive inside story of how The Wizard of Oz found its way from being a near-forgotten novel to one of the most beloved films ever made. In addition to Harburg and Arlen, this chapter makes reference to Arthur Freed, the ambitious assistant to producer Mervyn LeRoy and to composer John Green.)

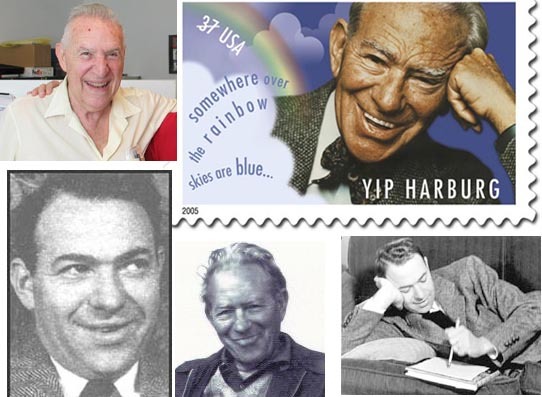

E.Y. “Yip” Harburg and Harold Arlen were hired on May 19, 1938, on a “flat deal,” a fourteen-week contract. They were paid $25,000, with one-third advanced against royalties. When they signed the contracts and were given the keys to the bungalow at MGM, the script was four months away from its final form, and the only actor already cast was Judy Garland. Instead of being attached to the film after the fact, they were, so to speak, in one the ground floor with a chance to help design the building that was rising around them.

June 1939: Standing, from left: Bert Lahr (the Cowardly Lion), Ray Bolger (the Scarecrow), MGM executive L. K. Sidney, Yip Harburg, composer/conductor Meredith Wilson (who later wrote The Music Man). Seated: Judy Garland and Harold Arlen. (Photo: The Yip Harburg Estate)

Arlen and Harburg wrote an integrated score in which every song commented on character or advanced the plot. The Freed Unit at MGM in later years polished and performed the integrated musical form. But Harbug does not remember that Freed ever asked him for an original score, “although he accepted the integrated concept quickly and was very encouraging.” Harburg was well aware of Love Me Tonight, High, Wide and Handsome and earlier attempts in the same direction by Ernst Lubitsch. “The trouble was, those stories didn’t give the lyric writer enough leeway. This story did.”

They first tackled what Arlen called “the lemon-drop songs.” Those were the light songs, emotionally undemanding and generally easy to write. “Ding Dong! The Witch Is Dead,” “We’re Off to See the Wizard,” “The Merry Old Land of Oz.” Nor was the song that set up the characters of the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman, and the Cowardly Lion difficult to write. The tune for “If I Only Had a Brain…a Heart…the Nerve” came out of the proverbial songwriter’s trunk. Under the title of “I’m Hanging On to You,” it had been written for Hooray For What! But not used in the show. Harburg simply wrote new words for the tune.

Whether a composer sets a lyricist’s words to music or a lyricist writes words to fit a composer’s tune depends on the two artists and their relationship. Most composers work one way with one lyricist, another way with a second. Richard Rodgers always wrote music to which Lorenz Hart later added lyrics. When Hard died and Rodgers started his collaboration with Oscar Hammerstein 2nd, he adapted to Hammerstein’s way of working and composed the music after Hammerstein wrote the words. Both Yip Harburg and Johnny Mercer usually added words to Arlen’s music. For Mercer, “Harold was a strong writer. He knew where he was going.” With Harburg, it was more of an intellectual decision. He was always extremely concerned “about boxing a composer in.” Although the subject matter and meaning of a song were usually discussed in advance, Harburg refused to corner Arlen with a lyric or even a title before Arlen had written at least part of a tune. Usually, Arlen gave Harburg the first eight bars. Harburg listened to them and came up with a title. Then Arlen completed the song before Harburg started on the lyrics.

Judy Garland, ‘I Could Go On Singing,’ the Harold Arlen-Yip Harburg title song from her final film, released in 1963.

Arlen rarely wrote his songs at the piano. He felt that tunes created at the piano were contrived and mechanical. Arlen, more than most songwriters, believed in inspiration. The idea for a melody would sometimes come when he was in a store or on the golf course, more often when he was aimlessly walking or driving. He would catch the melody by jotting a few notes in his notebook. Later, at the piano, he would develop the tune. Harburg would sit in the room while Arlen wrote a song. “He’d keep playing a line over until I learned it by heart. There was something about a composer playing a tune over and over for you. You couldn’t get away from it. Now I use a tape recorder. I capture everything the composer does, even if it’s going to be thrown away. Sometimes the asides give me an idea. I started using a tape recorder during my last collaboration with Arlen, when we did the title song for Judy Garland’s I Could Go On Singing in 1963.” When Arlen played a song over and over, Harburg “would hear words.” When the words didn’t make sense, he would go out in the garden and plant something while Arlen disappeared to look for a golf course. (In similar circumstances, Johnny Mercer and Arlen—who worked a more businesslike noon-to-6-p.m. day—would solve the problem of feeling stale by driving down to a Beverly Hills delicatessen for something to eat.) When Harburg was surfeited with music, he would leave Arlen’s house, go home to try to fit in the words, “turn dull,” telephone Arlen and go back to Arlen’s house to listen to him play.

By the time they started to work on The Wizard of Oz—Arlen was thirty-three and Harburg was forty—they were close friends and comfortable collaborators. Both friendship and collaboration had started with Harburg’s respect for Arlen’s music. In 1932, Harburg’s song “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” had become almost the battle hymn of the Depression. In the spring of 1934, the Schuberts had come to Harburg and asked him to do the lyrics for a new revue. He could choose his own composer. He chose Arlen, with whom he had casually written a few songs (including, with another collaborator, Billy Rose, “It’s Only a Paper Moon”). Arlen was so disturbed at the idea of turning his back on his usual lyricist, Ted Koehler, that he could not bear to tell Koehler about Harburg’s offer. He wrote and handed Koehler a letter describing it. Koehler’s response that Arlen would a fool not to take the job was not enough to assuage Arlen’s conscience. He took the job, but first he went out and got drunk.

When Harburg picked Arlen to compose what became Life Begins at 8:40, Arlen was a gay and funny young man of twenty-nine with a tinge of mysticism and a penchant for reading Marcus Aurelius. His father was a cantor, and he had been born Hyman Arluck into a rigidly Orthodox Jewish house. A promising piano student at ten, he had dropped out of high school to play piano. He had no idea then of becoming a composer. Arranging songs and playing the piano were means to the end of a career as a jazz singer. Extraordinarily handsome, outrageously spiffy in his blazers and foulard scarves, his spats, his homburg, and his cane, he probably could have been successful, “really successful as a singer,” said Mercer, “like Bing Crosby, who also started as a band singer around the same time.” But his singing career was over when, at twenty-four, he improvised a tune that lyricist Koehler turned into “Get Happy.” (Arlen is still considered the songwriter who could best sell his own songs by singing them, with the possible exception of Mercer.)

What John Green calls “the tragic metamorphosis of the happy young man” into the reclusive old one began with his marriage in 1937 to Anya Taranda. Anya, a showgirl, was not Jewish. Given the unspoken horror of hs family, it took Arlen five years to ask Anya to marry him, although John Green doubts that Arlen ever had a date with anybody else. Even then, he did not really ask her. He simply handed her a note telling her they would get married the next day, just as he had handed Koehler a letter telling him of Harburg’s offer. The marriage ended with Anya’s death in 1970, after years of mental illness.

But in the spring of 1938 Anya was still well and Arlen was still what Green remembers as “the greatest laugher I ever knew.” The lemon-drop songs had come easily to Arlen. The ballad was something else. “The ballad is always the hardest song to write in any structure,” according to Harburg, “because a ballad is pure melody. Also, the ballad is the one that has to hit the Hit Parade, the one everybody sings, the one that must be easy enough to sing. The ballad has to step out. A song’s life will depend on how good the show is. If it’s a good show, a song will step out. Even in a not-so-good show, a song can step out if it’s given a chance to breathe and a lot of luck.” Arlen and Harburg had agreed that the ballad in The Wizard of Oz would be “a song of yearning. Its object would be to delineate Dorothy and to give an emotional touch to the scene where she is frustrated and in trouble.”

Harold Arlen (standing) with E.Y. Yip Harburg

Then came the week-long struggle to find a melody. When the “broad, long-lined melody” did take possession of Arlen’s head, it was ironically attached to some peculiarly Hollywood symbols. He was on his way to the most garish of movie theaters—Grauman’s Chinese, where movie stars cemented their footprints in the forecourt—to see a movie. And he was exactly opposite Schwab’s drugstore where he told his wife to stop the car so he could jot down a tune. Schwab’s was already being fictionalized as the magic soda fountain where any good-looking girl who wanted to be a movie star would be handed an agent’s card before she finished her milkshake. It is doubtful whether any movie star was ever discovered inside the drugstore, but the melody of “Over the Rainbow” was composed outside the front door.

When the song was three-quarters finished (Arlen had not composed, nor did he at that time intend to compose, the childishly simple middle part), Arlen played it for Harburg. Harburg’s disappointment was obvious. He respected Judy Garland’s capabilities, but he thought the song too symphonic for any sixteen-year-old girl. “A song that’s done for a movie is custom-made. You have to write something that will fit a singer’s style and ability, but you also have to know the character that is being layed. Today, young composers beat out a one with rhythm and energy without any differentiation for character. Everything depends on the beat. Everything sounds the same. Somebody did a rock version of one of my plays. The young guy sang rock. Fine. So did his boss. When the hippie and the big executive both sing rock songs, the big executive loses his dignity and you lose the differentiation between the two. That’s why you’re not getting shows on Broadway except Godspell and Hair. They’re just infantile charades, all the characters drumming and the same yah-yah-yah. A songwriter, like a tailor, has got to measure his customer. Dick Powell was just a juvenile singer with a tenor voice. We could only give him a ballad wth a nice sentimental strain. We couldn’t give Bert Lahr a ballad at all unless it was satiric. Judy had a wide range. She could go from torch song to high humor. She ran the gamut of emotion. I knew Judy could sing ‘Over the Rainbow,’ but I thought it was too old for the character.”

Remembering, Harburg was sure that “I was fooled by the majestic and serious way Harold played the song.” Ira Gershwin, a customary arbiter, was asked to come over and listen. By the time Gershwin arrived, Arlen’s initial euphoria had been blunted by Harburg’s response. When he played the tune for Gershwin, it was with a certain embarrassment and hesitation. The melody sounded plainer, less important. Harburg had changed his mind before he heard Gershwin’s favorable opinion. “Even so, it was a daring song for a little girl. The songs in Disney’s Snow White had all been little jingles. ‘Some Day My Prince Will Come,’ ‘Heigh Ho, Heigh Ho.’ If you play ‘Over the Rainbow’ symphonically, it will stand up. If you play ‘Heigh Ho, Heigh Ho, It’s Off to Workd We Go,’ it won’t.”

To please Harburg, Arlen wrote the melody for the tinkling middle of the song:

Some-day I’ll wish upon a star

And wake up where the clouds are far behind me

Where troubles melt like lemon drops

Away above the chimney tops

That’s where you’ll find me.

It was an almost automatic thing for Arlen to do. “We’d instinctively give ach other clues about what we were thinking,” says Harburg nearly forty years later. “I’d incorporate his ideas into my lyrics. He’d incorporate my ideas into his music.”

Camera-buff Harold Arlen’s 16mm film of the portrait sittings for cast members of The Wizard of Oz and miscellaneous shots from the movie set

Sitting on a straight-backed kitchen chair in the California garden of a friend, eyes closed, a sun worshiper still, a small man as elflike as the leprechaun he created for Finian’s Rainbow, Harburg remembered bits and pieces of what had happened when Arlen left the ballad in his hands. “The girl was in trouble, but it was the trouble of a child. In Oliver, the little boy was in a similar situation, was running away. Someone thought up a song for him, ‘Where Is Love?’ How can a little boy sing about an adult emotion? I would never write ‘Where I Love?’ for a child. That’s analytical adult thinking, not childish thinking. This little girl thinks: My life is messed up. Where do I run? The song has to be full of childish pleasures. Of lemon drops. The book had said Kansas was an arid place where not even flowers grew. The only colorful thing Dorothy saw, occasionally, was a rainbow. I thought that the rainbow could be a bridge from one place to another. A rainbow gave us a visual reason for going to a new land and a reason for changing to color. ‘Over the Rainbow Is Where I Want to Be’ was my title, the title I gave Harold. A title has to ring a bell, has to blow a couple of Roman candles off. But he gave me a tune with those first two notes. I tried I’ll go over the rainbow, Someday over the rainbow. I had difficulty coming to the idea of Somewhere. For a while I thought I would just leave those first two notes out. It was a long time before I came to Somewhere over the rainbow.”

‘Why does she sing in a barnyard?’

When, after the first sneak preview, L.B. Mayer removed “Over the Rainbow” from The Wizard of Oz, Harburg, Arlen, and Freed were outraged. Losing “Over the Rainbow” did not simply mean losing a pretty ballad; it meant losing the dramatic point of the whole Kansas preface—a consideration that escaped the numerous producers who complained to Mervyn LeRoy and L.B. Mayer. “Why does she sing in a barnyard?” they asked. Those complaints began almost as soon as “The End” was flashed onto the screen in San Bernardino. San Bernardino was seventy miles from Los Angeles, but it was typical for MGM producers to show up at previews of their rivals’ films. (Arthur Freed, during the days when he was trying to get a handhold as a producer, rarely missed a preview and never missed an opportunity to give his opinion of the picture.) And LeRoy, the interloper from Warner Bros., was not one of the MGM producers’ own. Their virulent response to “Over the Rainbow” may have been more an attempt to embarrass LeRoy than reasoned musical judgment.

Harburg remembered that first preview as “unbearable. You were always working with people who knew nothing, working with the ignominy of ignorance. Those ignorant jerks. Money is power. Money rules the roost. The artist is lucky if he can get a few licks in.” In 1976, LeRoy’s and Harburg’s memories diverged quite strongly over what happened next. LeRoy insisted that he had known the worth of the song and refused even to try the film with the song out. Harburg remembered that the song was removed and that it was Arthur Freed—pleading with Mayer, shouting at Mayer, using every bit of leverage his friendship with Mayer could give him—who forced the song’s return.

Judy Garland, ‘Over the Rainbow,’ by E.Y. Yip Harburg & Harold Arlen, from The Wizard of Oz

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024