String Fever

TheBluegrassSpecial.com Interview: Mark O'Connor

'The will to be at the top of my game has only gained with each decade'

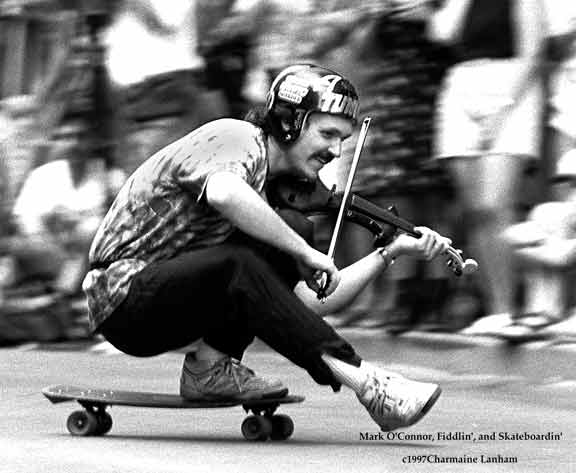

Mark O'Connor was a champion ark skate boarder in high school. He's show here in action, in a photo from 1997, wowing the crowd at the Nashville Summer Lights Festival with an exhibition of hot fiddling and daring skateboarding all at once.

Photo:Charmaine LanhamHere's a sampling of recent and forthcoming recording projects from Mark O'Connor, dating back to last year: in August 2008 O'Connor's own label, OMAC Records, released the fiddler extraordinaire's Double Violin Concerto, in which he teams with the towering classical violinist Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg; in December, the Eroica Trio released O'Connor's Piano Trio No. 1, "Poets and Prophets," his impressionistic tribute to Johnny Cash, originally composed in 2003 and now also part of a collaboration in song with Rosanne Cash that has played the Library of Congress, among other high-profile venues; his first symphony, Americana Symphony by the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra as conducted by Marin Alsop, will be issued on OMAC Records on March 10, 2009; a live album by his Hot Swing trio, recorded four years ago but unreleased in the aftermath of his distributor's bankruptcy, will finally getting a proper debut this year (parts of it have leaked out surreptitiously over the years, via sources unknown to O'Connor) and the Hot Swing group will resurface as well, but reconstituted as a quartet with a new bassist and acclaimed guitarist Julian Loge joining O'Connor and original Hot Swing guitarist, veteran Frank Vignola.

All of this recording activity is part of O'Connor's journey in taking the American Classical movement towards a new horizon marked bynewly written pieces incorporating contemporary musical styles into the traditional repertoire, and indeed, a defined method—the O'Connor Method, which the artist has fashioned with the help of nationally known string educator Bob Phillips and will be published in two volumes this year by Alfred Publishing. To further that aim, O'Connor is expanding his widely hailed string camps by introducing one to his new home town, New York City, where the Seattle native has lived for the past three years. The New York City string camp will take place July 27-July 31 employing a host of skilled teachers, and featuring faculty concerts that will be open to the public, along with a brand-new Teacher's Training Course that O'Connor himself will lead.

Born in Seattle on August 5, 1961, O'Connor was winning fiddling competitions (and ark skateboarding competitions) before he had reached his teens, and quickly became a fixture on the Nashville studio scene as the most in-demand fiddler in town, strictly first-call, triple-scale all the way. But in those years when he was setting the standard for a new generation of country and bluegrass fiddlers, O'Connor was also nurturing a near-lifelong interest in classical music composition. Not long after winning a Grammy for his 1991 album, New Nashville Cats, he turned away from session work for good and began remaking himself as an artist. In 1995 he unveiled his first classical work, The Fiddle Concerto, which has become one of the most performed modern violin concertos of the current era; his classical portfolio now includes Appalachia Waltz, a collaboration with Yo-Yo Ma and Edgar Meyer; Fanfare for the Volunteer, recorded with the London Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Steven Mercurio; the aforementioned Double Violin Concerto recorded with Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg; a Double Concert for Violin and Cello; string quartets, piano trios; a flute concerto, caprices-and a rousingly received tribute to one of his mentors, the French jazz great Stephane Grappelli, via his Hot Swing project. The catalogue is, to put it mildly, quite impressive and testimony not only to the breadth and depth of O'Connor's artistry, but also to his work ethic, his musical and intellectual curiosity, and to his sense of mission. It all amounts to one of the great American musical odysseys of our time, one that O'Connor has steered with great discipline, serious thought and an intense drive to challenge himself as an artist at ever opportunity. His is a life of constant movement and growth, with no wasted moments.

TheBluegrassSpecial.com checked in with O'Connor in December to discuss his agenda for 2009. As usual, he provided thoughtful, in-depth answers revelatory of the passion he brings to all these projects, particularly with regard to an ongoing commitment to education via his string camps.. O'Connor discusses all this activity and more in the following exclusive interview.

***

When we first chatted in 1991 the New Nashville Cats was out and it was about a week after you had introduced a composition you had written for classical guitar during a set at the Bluebird Café. A lot of people who were in attendance that night were surprised because hardly anyone knew of your interest in classical music. During our interview you outlined a couple of decisions you had made with regard to your career. This was pre-string camp, too, because in that interview you discussed your interest in education and what you could give to younger players coming up. But the big news coming out of that interview was your decision to leave session work—at a time when you were the most in-demand fiddle player anywhere, but especially in Nashville—and that you were gong to pursue classical composition as far as it would take you. From that time forward you've grown with each album, taken more chances, explored some daring ideas.

Mark O'Connor: The longer I live the more reflective I get (laughs), but I guess that's normal for anyone. I look back at my earlier years, and I know I was very talented. I was a child prodigy. But I did not max out my talent. I was one of those types that could coast—I could show up at the last minute, cram for the exam, pull it off, blow on my knuckles and go, "Hey!" But now I prepare so much. I prepare for rehearsals—like I had my string quartet rehearsal the last couple of days, which I'm very excited about. I have a brand-new string quartet of the top chamber music players in the world—Matt Haimovitz on cello, Ida Kavafian on violin and Paul Neubauer on viola. They're going to record my String Quartet No. 2 and No. 3 in January. We'd already played this material this summer several times, we'd rehearsed it for days and days, and I'm sitting here practicing for my rehearsal. This is something I didn't do in my twenties! I feel like the will to be at the top of my game has only gained with each decade. I guess I've always been a bit of a perfectionist, but I think I spend a lot more time preparing and making sure that I uncover every stone.

Of his forthcoming Americana Symphony, recorded by the Baltimore Symphony as conducted by Marin Alsop, O'Connor says: 'It was one of the most awesome projects I've every undertaken. I've composed several concerti, but to sustain a full-blown orchestra for that amount of time, plus a lot of percussion, gosh, a lot of detail, it was an incredible feeling.'Every new album of yours I regard as the result of a new challenge you've posed for yourself, because each one carries a surprise with it-is it going to be a classical album, a folk album, a country album? Is it going to be a trio, a string quartet, a full band? Unpredictable.

O'Connor: My next album is a symphony, The Americana Symphony, an incredible undertaking. I've composed several concerti, but to sustain a full-blown orchestra for that amount of time, plus a lot of percussion, gosh, a lot of detail, it was an incredible feeling. And to have the Baltimore Symphony record it so well—I mean, a pristine performance with Marin Alsop, Musical America's Conductor of the Year, doing it in her big year. That's scheduled for release on March 10.

I've got so much material. Record sales are a different barometer now. You are only as good as what your last record sold, but in today's climate, no one's selling much, so hey, I'm going to go for the volume of material and achievement. My distributor's bankruptcy really put me behind a few years, so I'm re-releasing Hot Swing Live In New York, and it's essentially going to be a new album, even though I recorded it about four years ago. It'll be new even to most of my friends.

The educational idea you pursued was the string camp, which you started while you were still living in Nashville. You could have kept it there and not done any others. But when you relocated to the west coast you started one in San Diego as well. Now you're living in New York and you're introducing a camp here, which you certainly did not have to do, given all the challenges such an endeavor poses. Why is this matter of education so important to you?

O'Connor: I remember the moment I got this idea after receiving my first Grammy. It caused me to wonder, What does it mean to be a professional in music, getting a Grammy? When I finally achieved this amazing thing, I partied for 24 hours, didn't go to sleep, finally went to sleep with my Grammy on the pillow, the whole deal. I woke up with a hangover and wondered, What now? Why don't I feel any better than I did 24 hours ago? It's not about winning a Grammy, is it? It's about creating a legacy for your music and your efforts, and I thought, I need to step up in that department, make sure people know about my heroes—and I was working on my Heroes album at that time. So that had a lot to do with it. I realized that a lot of people who might know Pinchas Zukerman might not know Byron Berline or El Shankar, and vice versa. As a matter of fact, I interviewed a lot of my friends, and I could find only two people at that time that knew all of my heroes. Those people were Darol Anger and Matt Glaser. [Ed. note: Anger and Glaser will be teaching at O'Connor's New York string camp.] They were the only two players who actually knew who Texas Shorty was, Benny Thomasson, Stephane Grappelli, Jean-Luc Ponty, El Shankar, the whole thing. I went, Oh, my gosh. This is going to be something worth pursuing. And now there are so many others who know all those people. I feel like I had something to do with that.

The New York camp feels like a coming out celebration. The storyline is the camp started 15 years ago in the hills of Tennessee, and I tried it out in an urban setting in San Diego to great success, and now we're ready for a major music center like New York. Another good thing is that we've got a great region you can access by train, and in this economic climate that's probably going to help us.

Are there going to be any changes from the format of the Tennessee and San Diego camps?

O'Connor: I'm actually going to change the format a little bit in all my camps. I did a lot of internal reviewing and updating what our students are looking for via a lot of questionnaires and thought. You know, I've been putting on the camps for 15 years. Fifteen years ago it was a different world. It was before the Internet, mostly, before people had websites, before YouTube, MySpace, all this stuff. So I designed the camp to be more introductory to students and largely that's how I've been handling the curricula.

Now, we can get a little more involved from day one. We don't necessarily have to introduce each other because there's so much access technologically to all my teachers, which is something that was not there 15 years ago. A lot of people had no way to know who these people were, even though some of them were legendary. Still, some hadn't had records out in many years. So I'm excited. I've decided to ask each instructor to label his or her classes something specific, and we're going to begin on Monday and dive into the literature. And it'll be even more comprehensive than it was before.

These camps are not for beginners, correct?

O'Connor: Right. We had a beginning aspect to it, but we realized that when people are beginning, sometimes it's really beginning—like how you hold the instrument. We can't ask Darol Anger, Tracy Silverman, Matt Glaser to teach people how to hold an instrument. So I had to hire extra help to teach those beginners. It turned out that it was a wash from a cost effective standpoint. And it didn't really help what I wanted to do, which was to spread all this wonderful literature. There's plenty of beginning teachers out there, thankfully; what we have trouble finding is advanced teachers for all this great music. So I'm thinking we omit the beginning students and beginning teachers and free up some room, maybe sneak in a few more advanced people, and that will brighten everybody's day. (Laughs) It'll shorten the food lines for sure!

But if you're a parent reading about this, or someone who's starting to play and has been teaching himself or herself for some time, how do you determine if your child or you are at a level that will work for this camp? When are you not a beginner anymore, in terms of this camp?

O'Connor: We like to say an intermediate knows how to play the instrument, knows some repertoire, and if you wanted to be specific in the genres, say if you're a Suzuki student you're at least in book two; if you're an old-time bluegrass fiddler, you know at least ten or fifteen tunes. If you're on your way, you can participate in an intermediate class. I like to think of intermediates as having at least a year behind them. People progress at different rates, so it's hard to say it has to be a year, but what we don't need are people who are just beginning. That's for another camp. So we hope people will self-audit and put themselves in the right class. We don't have time or the resources to audition people. We're going to have three camps, and if we fill them all up, which is our hope, that's six hundred students. Now for every six hundred students, there's probably another six hundred who inquire about the camps. So we're talking having someone possibly listening to 1200 tapes? That's just beyond our comprehension. And we sort of really want to instill this community attitude—we don't want to audition you but rather depend on you to know where you should go in our course.

I notice on your website a $300 fee for what you're calling a "Teacher's Training Course." Is that a new wrinkle in the camps?

O'Connor: Brand new. I had this idea the last couple of years to create a violin method. Some of the significant violin players in the past who were pedagogues have created violin methods. I've been touting this idea of an American string school of music for some time now, and my camps are part of that, even though we have some world music there. But a lot of what we've been doing is describing how broad and wide ranging the American string style can be. So it dawned on me that I should consider designing a method. I approached Alfred Publishing, and we talked it over and it happened. So I've been at work all year and I've got Method Book one and two finished. Those will be introduced to the market on March 1.

And both books will be available for sale to the general public? I could walk in and buy one?

O'Connor: You can buy one. It will come with a companion CD that I recorded. I recorded each of the tunes that are featured in the books and it's laid out in a pedagogical way in that each tune introduces a new type of technique, whether it's a new use of a third finger or the use of another string, all the way through. I've arranged some really cool repertoire that is part of our American history and tradition, and I've also composed a lot of beginning tunes and exercises for it. It's been a very rewarding experience. I even did an arrangement of Dvorak's New World Symphony where I take a couple of the main themes and create new fiddle tunes out of them. And I create a tune from "Simple Gifts," I create a tune from Copland's "Hoedown"; there are a lot of historical references, a lot of old chestnuts like "Sweet Betsy from Pike," "When the Saints Go Marching In," and these will aid the student in learning how to play the violin. What's missing largely in the fiddle world is a method book. There are a lot of books with beginning tunes, and then it's up to the teacher to figure out which tune to have a student learn in a particular week. This actually is a whole method where each tune not only introduces the techniques, the styles and the skill, but also exercises for each song and what we're calling ear training, where it starts to develop a student's ear and hearing from the very beginning rather than introduce that later—in some cases much, much later and maybe too late.

The other key component of it is that I tried to pick and create material that felt timeless. By that I mean material that will stay with you, not songs you will only play when you're seven years old, like a lot of "children's" songs. These are tunes you'll play, if you want to, when you're forty, and when you're seventy. I really wanted to make the literature count. We mirrored the Suzuki method in some ways because it's a very successful method and there are a lot of good things about it. Also, Alfred Publishing owns Suzuki, so the company is willing to introduce this new American string method realizing it is either a companion piece or a competitive piece to its own Suzuki method.

Given that fact, I decided to have my co-author Bob Phillips, who helped me with a lot of the technical and pedagogical parts of this method, also help me teach a Teacher's Training Course. I thought how wonderful that would be to get a teacher involved, totally get into this method, then go back home and, say they had been teaching Suzuki or they had been teaching maybe a combination of a couple of different methods, decide to try this O'Connor Method for awhile with the students. That would be a wonderful legacy that the camp could provide.

'The New York string camp feels like a coming out celebration. The storyline is the camp started 15 years ago in the hills of Tennessee, and I tried it out in an urban setting in San Diego to great success, and now we're ready for a major music center like New York.'Are the Teacher's Training Courses going to be offered at all the camps or only in New York?

O'Connor: We're going to start with the one in New York to see how it goes. Bob is a busy clinician so I didn't want to accost him for all three. But if it goes well and people sign up, then I'm sure he will be back and we can expand it. We can even have other teachers possibly out of this first session help me with subsequent classes. There will be things I'll be able to do at these Teacher's Training Courses, but some of the things I'm not qualified to do because this is beginning, and what I was able to do in this book is create repertoire. But I really needed assistance technically in, for instance, can a student move his or her second finger this far up the fingerboard? That's the part I don't know and where I needed strict guidance in creating that.

Isn't there a possibility too that this Method could find its way into the public education system in this country?

O'Connor: Exactly. We actually are going to introduce the method at the American String Teacher's Association Convention mid-March in Atlanta. So we'll have a forum where literally hundreds of teachers can hear us talk about this method. It will be for sale there, too. So having the training course at the camp hopefully is very small part of what the method book could do out there, because it really is for on-site teacher's studios and public schools. Eventually I'm going to have the method book translated to include viola, cello and bass for the repertoire that's appropriate and have a lot of the material arranged for junior high and high school orchestra. So there's an inter-dependence, so to speak, where the same repertoire will be coming up with the same kind of renditions. You know a lot of the students are going to be very familiar with these songs, but I tried to pick out note choices and such that I felt were both technically sound and also very secure artistically. Sometimes when beginning teachers get hold of material they dumb it down to the point where you would never want to play it on stage, really. So I just tried to guide it in a way that was still very beautiful.

And are the camp students going to be given, or are they given, one-on-one and group lessons, or is it totally a group situation?

O'Connor: It's totally a group situation, because of the numbers. I've been working on bringing the camp to New York for about five years. We've researched every imaginable way to put it on and I am really happy in how we ended up doing it. There are a lot of things to consider. One thing that's more confusing here is the number of potential places where it could be held. So it makes your research a little harder. For instance, in San Diego, when I was looking around for places to hold it there, there were only a couple of options to consider. So I just held out for the place I wanted. But in New York there are so many options and so many ideas, and people wanted to put in their two cents, but I'm glad how it turned out.

We'll be encapsuling the whole block between the concert hall at the Society for Ethical Culture, the Ethical Culture Fieldston School and the YMCA, where everybody will be staying overnight. And it's so close to the middle of the string world of the planet, with Lincoln Center and Juilliard right there. We've got a fantastic lineup of teachers—some of the very best we've ever had over the course of the camps' history. We've got a couple of fairly new faces as well—such as Mysore Manjunuth, the incredible East Indian virtuoso. I'm very excited about it and I'm also excited about the fact that in New York we can open up the faculty concerts to the public. So our camp can act as a community expander. It's not going to be in a vacuum like it is in Tennessee, where we've had to put a guard at the gate to keep people out. [Ed. Note: The Tennesse string camp was held in Montgomery Bell Sttae Park.] Here, we're going to say, "Come on in!" Not to the classes, but to the faculty concerts.

The Eroica Trio (from left: violinist Adela Peña, pianist Erika Nickrenz, cellist Sara Sant'Ambrogio) has released its recording of O'Connor's 'Poets & Prophets' composition (on the album An American Journey, which also features new arrangements of Porgy and Bess and West Side Story), a work inspired by and honoring the music of Johnny Cash: 'It's unique in that it actually resonates with a group like the Eroica Trio or other classical musicians to such an extent, and I think this is exactly what I've been looking for in my music.'With regard to your own musical projects, beyond the camp, the work you titled "Poets and Prophets" is finally out on record, as performed by the Eroica Trio. You originally composed this work for the Eroica Trio back in 2003. Are you ever going to record it yourself?

O'Connor: Yes. The "Poets and Prophets" piece has been a wonderful project for me. In a career like mine that's been so unique, it's even more unique. It's unique in that it actually resonates with a group like the Eroica Trio or other classical musicians to such an extent. This is exactly what I've been looking for in my music. A lot of musicians have said in the past, "Mark's music is so unique that you can only imagine him playing it." I've heard that quite a bit, even though I don't agree with it. Then here comes the Eroica Trio, plays my music and does an unbelievable job with it, gets all kind of critical attention and it makes NPR's "Top Classical Albums of the Year" list. Eroica has had a lot of success performing it in concert, and they love the piece. They've been playing it for years, but it's taken them awhile to get it actually recorded because the recording situation with classical labels has slowed down a bit. But they finally got it out. In the meantime, I didn't know they were going to release it, and I'm thinking, Gee, I don't know if I can wait around forever, so I went ahead and recorded it with a piano trio I've put together, with the thought that I'll have it in the can and I can release it if Eroica doesn't release it. But if they do release it, I'll wait a year or so. So that's my plan now. I actually have recorded it.

In the meantime I've put it together with the Rosanne Cash "Poets and Prophets" performance collaboration, which has been a remarkable success. We just played at the Library of Congress and we've got several more dates coming up, including Princeton in the spring. That enables me to come full circle, having Cash's daughter collaborating with it, and at the end of the concert I've arranged for the piano trio to do two of Rosanne's songs that she wrote about her father, with her singing. So artistically there's a huge full circle. It's been an absolute privilege to put these projects together with Eroica Trio, with Rosanne Cash and with my own piano trio. So here's a piece that already has three stories to it. It's one of those lucky artistic ideas I've had.

Of his collaboration with Roseanne Cash on a tribute to her father, Johnny, a childhood hero of his, O'Connor says: 'There's so much about this project that makes sense. Even though the music stretches the imagination with what we're putting in one show, I think it makes sense artistically and in a human way as well.'Rose is very careful about protecting her father's legacy and what she chooses to get involved in. I'm not surprised that the two of you would get together because I'm sure she has a deep respect for your work, but who approached whom with this idea?

O'Connor: Well, when I first composed it, I let her know about it, and she said, "Wonderful. I'd like to hear it one day." Then after premiering it, Eroica decided to do a little demo recording; went in for three hours and just put it down so we'd have a tape to play for people, so Eroica could get more concerts with it. That's the tape I sent Rosanne. She wrote back and said she absolutely loved it. When I moved to New York three years ago, she was the only person from Nashville I knew that lived here. I called her and we met at Columbus Circle for lunch, and I said, "If you ever want to do a collaborative concert where I play 'Poets and Prophets' and you sing the material you've been writing about your father..." and she loved the idea. We staged it at Merkin Hall to try it out about two years ago and it was a big success. Then we decided to put together a few dates to really see if the show works. So we played it three or four times, including at the Library of Congress and the New Haven Arts & Ideas, and it went really, really well. It's nice because it's my trio and then Rosanne's trio; she breaks out her band in an acoustic setting. It gives us both a different look to the audience, and we draw from different sectors, plus there's a lot of interaction and a lot of history—we've known each other for almost twenty-five years. Of course I worked with Johnny Cash, who was my boyhood idol. Lots of interesting connections.

What's more, I think people, in this day and age, when there's a lot of things put together and packaged, people are always struggling—especially serious artistic followers—with "What's the sense of that?" or "What's the connection?" There's so much about this project that makes sense. Even though the music stretches the imagination with what we're putting in one show, I think it makes sense artistically and in a human way as well.

You could revisit this project for years.

O'Connor: That's true. Rosanne's lyrics have a timeless quality, and I wanted to write the music to where it's just Americana. I do feel like Johnny Cash would have liked this piece. I remember one day I was walking through the airport terminal in Nashville, and this guy and this gal are waving to me from across the terminal. They recognized me, and it was Johnny Cash and June Carter. They were saying, "Come over here!" And waving me over. So I go over there, and you know how couples, especially famous couples, stick together in public places. They just separated. June went one seat over, and they were facing into the terminal, so all these people were walking by and they sat me in between them. So Johnny Cash was on my right, June Carter was on my left, I was sitting there with my bag and my violin, and all these people were walking by not noticing it was Johnny Cash and June Carter, because they weren't paying attention. Johnny and June were talking to me and my head was bobbing back and forth, over to the right, over to the left, and this took place for about fifteen minutes. I was so profoundly moved by that whole scene. That's one of the memories I channeled when I wrote that slow third movement for June, because I could feel the intensity of the couple. It was so amazing and so warm that they were able to divide and put me in the middle—it seemed unusual to be in that situation. I thought, What a nice memory. So anyway, I put a lot of emotion into it, and I really channeled the Eroica Trio's intensity as well. One of the things the Eroica Trio has that's very palpable is a charismatic presence. Believe it or not, I tried to draw a line from Johnny Cash's charismatic presence to the Eroica Trio's charismatic presence as one of my bridges. I think it somehow affected some of the musical content, in how I was able to deliver it. There's some kind of connection there that resonates with the listener.

So you're capturing their personality as well as his.

O'Connor: Exactly.

Did you map it out as we hear it on the record, or did it undergo some dramatic change during the compositional process from your original vision of the piece?

O'Connor: No, I mapped it out. I decided to start present day and work backwards. Because I kind of played off that single "Hurt" on the first movement. It was very stark and contemporary and it presented Cash in a whole new light. That's how it dawned on me that I could work from that angle, introducing the sounds of the trio in more of a stark and contemporary manner, then as it goes into the piece, dive more and more into the vernacular, where Cash comes from.

The Chamber Music Summer Fest, in La Jolla, California, a major classical chamber festival, is going to give me an entire night this summer, and the headlining piece will be "Poets and Prophets," in a night of all my music. One of the latest competition winners, who's playing with all the major orchestras this year, is going to play the piano part. People are picking up on it. I heard it was played at a major festival in Korea and in Seattle.

Now how are you going to boil down everything you've done into a night of your music?

O'Connor: (laughs) I know. I guess it's picking and choosing.

It'll be interesting to hear what you come up with. I want to see the program for that one.

O'Connor: I'm trying to do more of my recent work, but I have to throw in some older stuff too. Which makes sense, I guess.

What else is on your calendar for 2009? You've outlined a busy schedule, but I'm guessing that's not all there is to it.

O'Connor: Well, I'm returning to the Great Aspen Music Festival for another special collaboration with Sharon Isbin, the Grammy winning classical guitarist. I composed a duet for us that will be released on Sony and we'll perform it there. Also, I've been doing these high-profile residencies where I come into a major university or music school and I'll spend a couple of days performing solo, and I'll teach a couple of classes on material that I've performed, to their best students. I'm doing that at some of the most high-profile music conservatories in the world. I did it at Rice, I just did it at Curtis, I've got Indiana University on board, and the Cleveland Music Institute. Those are scheduled, and several others.

And I've got late breaking news: I'm reconstituting my Hot Swing group, and it's going to feature two guitarists this time, Frank Vignola and Julian Loge. The album, Live in New York, has not really been released. I tried to release it about three years ago, and my distributor went bankrupt right at the moment it was coming out. So copies ended up on the inventory floor. But a couple of copies have leaked out, because that's the way this works, I guess. So we're officially releasing it with my new distributor on January 13. It's Hot Swing, and I'm very excited about it because it completes the trilogy of Hot Swing recordings. Over a nine-year period we've been playing with that cast of Jon Burr and Frank Vignola, and the live disc really captures how intense and sophisticated Hot Swing was able to get. Now I've changed personnel a little bit, got Frank Vignola back, added another guitarist who's equally wonderful, Julian Loge, and have enlisted another bass player, so it's quartet. Ted Kurland is going to book that as an independent act for me, which literally just happened in the last week or two [editor's note: this interview was conducted on December 17, 2008.]

I can't let you go without asking about someone you worked with, Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg. She's one of my favorites. Her playing is so incredibly intense and electrifying. What was it like being in the studio with her?

O'Connor: I'm glad you asked about that. That's my current record that's been re-released, technically, because it was part of the distributor's bankruptcy (Double Violin Concerto, with Marin Alsop conducting the Colorado Symphony Orchestra features O'Connor with Salerno-Sonnenberg on two O'Connor compositions, "Double Violin Concerto for 2 Violins and Orchestra" and "Appalachia Waltz"; two other cuts feature O'Connor's "Johnny Appleseed Suite" performed by O'Connor, with Bryan Sutton and John Jarvis, along with the Orchestra; and O'Connor performing his arrangement of "Amazing Grace" with the Orchestra). It's getting a lot of airplay—82 stations are playing it already after six weeks in release. Working with her was (laughs) high octane. First of all, our two personalities are kind of polar opposites. I'm kind of mellow and laid back, and she's very vibrant and Type A. Then there's our musical personalities, which are both very intense but in different ways that get different types of musical results. So it's a really interesting combination of violin playing and people and histories. We're the same age and really got on and liked each other a lot. Matter of fact, she is the current director of a brand-new chamber orchestra in San Francisco. This is not a done deal, but she's pursuing me to be a composer-in-residence for them. She really loves my music, and it's very gratifying to have that respect from someone who's literally at the top of the classical violin world for so long-it's so hard to get there and to stay there for awhile. Only a few people can do that. Nadja's been one of those great artists. And actually, to be a female violinist when she came along, and to rise to the top, was even harder. Now it's going to be much easier for women to follow her.

'I was thinking this was as good as I was going to get,' O'Connor recalls of his first meeting with the classical giant Yo-Yo Ma, 'then all of a sudden I meet up with Yo-Yo Ma in '95 and I realized I could take my playing to another level playing with this person'She's an incredible player. When she enters a composition, you immediately know it's her—that's how distinctive her instrumental voice is.

O'Connor: It's a wonderful thing that's been a little lost in recent violin playing, the incredible character of sound; the uniqueness from player to player has been lost a little bit. Nadja went to Juilliard and Curtis, so it's not like you can say she didn't go to music school, so she doesn't sound like anybody else. I think she's just a great, great artist. I learned a lot about violin playing from Yo-Yo Ma and from Nadja. It's funny, when I look back at my career and development, what I needed happened at exactly the right time. Like when I really needed Benny Thomasson, he came into my life when I was 12 years old. When I really needed the next jolt, at 17, Grappelli came in. Then I'm basically on my own all the way through Nashville, creating my own sound and developing my own thing. Then as I was thinking this was as good as I was going to get, all of a sudden I meet up with Yo-Yo Ma in '95 and I realized I could take my playing to another level playing with this person. I really learned a lot from him as a player. And Nadja soon after that. I think between Nadja and Yo-Yo I really developed a lot of my ability to project in a hall; I got a bigger sound, a louder sound, and I was able to articulate my own pieces and concertos much better. When I first started playing my Fiddle Concerto, what? Eighteen years ago? I was playing it through a little amplifier. I didn't know how to play in a way that I could project into a hall. Now when I play a concerto I can be heard over an orchestra. That's something I developed in my thirties, where most people would develop that as a younger person. So you're never done learning about yourself. And in trading licks with people like Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg, and the other violin players I've worked with too, such as Joel Smirnoff and other greats I've come in contact with, I've learned about myself.

Then all through this I'm getting to compose music for all of them to play. So I'm getting to learn at the same time I'm getting to spread my talent out there and have them endorse my music. It's been a wonderful situation, and I'm looking forward to getting a lot of my newest work out. I'm looking at my career now as being in three phases: I had my childhood with the early fiddling and early bluegrass and the competition wins; I had my whole Nashville phase, which included my recordings New Nashville Cats, Strength In Numbers, all that stuff with Bela Fleck and Edgar Meyer; then I had the third phase, with the centerpiece being "Appalachia Waltz" and my work with orchestra and Nadja and that whole thing. Now, I'm hoping there's a fourth phase I'm coming into, with a lot of my new music, a further distillation of an American style of classical music and how it can impact the symphony orchestra, the string quartet and the piano trio, which are the three major genres. When I was working with Yo-Yo, those were string trios. String trios are a little bit of a novelty; there's very few string trios written. So that project, although it was very successful, had a bit of novelty ring to it. What I'm doing different now is taking those kinds of stylistic leaps and inserting them into more concertos and a symphony for the first time, and the string quartet and piano trio, into the serious genres. There's very few string trios out there that would even work, you know, but now there might be some serious string quartets or serious piano trios that will consider this music. So I'm hoping this fourth phase will bring the three other phases together and produce a new American music style, a new American string school with the camps as part of it, along with the method books, the whole thing.

A selection of albums mentioned in this interview:

An American Journey (2008)

The Eroica Trio

EMI Classics

Buy it at www.amazon.com

The Fiddle Concerto (1995)

Mark O'Connor,

Warner Bros.

Buy it at www.amazon.com

Appalachian Journey (2000)

Mark O'Connor, Yo-Yo Ma, Edgar Meyer

Sony

Buy it at www.amazon.com

Double Violin Concerto (2005)

Mark O'Connor, Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg

Colorado Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Marin Alsop

OMAC Records

Buy it at www.amazon.com

The Essential Mark O'Connor (2007

Sony Classics

A two-disc overview of O'Connor's classical and hot swing compositions, featuring Yo-Yo Ma, Edgar Meyer, Wynton Marsalis, the Hot Swing Trio (O'Connor, Frank Vignola, Jon Burr), the Metamorphosen Chamber Orchestra and the London Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Steven Mercurio

Buy it at www.amazon.com

Americana Symphony (2009)

Mark O'Connor, Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Marin Alsop

OMAC Records

Available, March 2009

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024