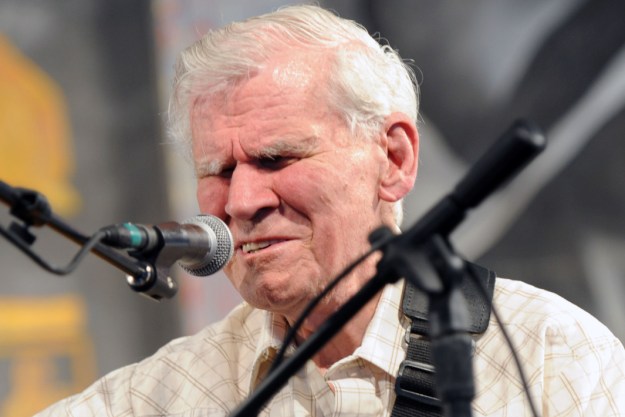

(Photo: Rick Diamond)Farewell to an American Institution

When Arthel Lane “Doc” Watson crossed over on May 29, at age 89, it was like a gut-punch to anyone who loves roots music at its most authentic. Blinded by an infection before his first birthday but undaunted by his seeming handicap, Arthel was raised with a staunch work ethic; indeed, he earned money to buy his first guitar by chopping down dead chestnut trees on his family’s property so his father could sell the wood for money. Influenced by the Carter Family (“When Roses Bloom in Dixieland” was the first song he learned to play on his new guitar) and Jimmie Rodgers (“Jimmie Rodgers was the first man that I started to claim as my favorite,” he said), Watson began playing country favorites of the day on local street corners and in the process became accomplished in flat- and fingerpicking. In short order, he would also master the banjo. He became a repository of rural American ballads, some of which might have been lost to history had Doc not preserved them in his repertoire. (By the by, he took the nickname “Doc” from Sherlock Holmes’s sidekick, Dr. Watson.)

Doc Watson’s short course in ‘Black Mountain Rag.’ His version is described by Bill C. Malone as ‘one of the classics of modern guitar picking.’As great a musician and singer as he was (and there was nothing quite like the sturdiness of Doc’s rich baritone voice—on his 1975 album Memories he cut a version of Pat Boone’s teen tragedy hit “Moody River” that was remade into something approaching an Appalachian murder ballad, an altogehter new and mesmerizing realization of a song that defeated no less a vocalist than Frank Sinatra), many of Doc’s fans will first mention his good humor as his most admirable quality. He seemed always to have a smile on his face, especially when he was on stage playing the songs he loved and felt to his core. In conversation he was gentle, warm and laid back; you got the sense if something wicked his way came, it would just roll off Doc and life would go on unaltered. Even after his beloved son Merle, with whom Doc had performed the most amazing shows for a decade and a half, died in an accident on the family farm in 1985, Doc never showed the public the enduring pain and sorrow he carried in his soul from this most unendurable loss. He was some kind of man, Doc.

Doc Watson and Jack Lawrence, ‘Tennessee Stud,’ a certified Doc classicThe most astute assessments of Doc Watson’s contribution to American music come from two quarters. In his essential Country Music USA, Bill C. Malone has this to say about Doc:

One of the most beneficial consequences of the country-urban folk interrelationship was the discovery of Arthel “Doc” Watson, one of country music’s most superb entertainers. Watson was a blind musician and singer from Deep Gap, North Carolina, who had performed locally for years, as both an acoustic and electric guitarist, until 1960 when he was “discovered” by Ralph Rinzler as a byproduct of the latter’s interest in Clarence “Tom” Ashley. With Rinzler as his manager, Watson began appearing at folk concerts in the North, first with his Tennessee and North Carolina friends, Ashley, Fred Price, and Clint Howard, and after 1964 as a solo act. Watson amazed his new-found audiences with his storehouse of songs, his skill as a banjoist and French harp player, and above all, his virtuosity as a flat-picking guitarist. Watson was not the first guitarist to play fiddle tunes on his instrument, or to otherwise play melodies with great rapidity (he freely admits his indebtedness to such musicians as Don Reno, Grady Martin, Merle Travis, and the Delmore Brothers), but he probably did most to revitalize the acoustic guitar and to encourage the flat-picking technique. His version of “Black Mountain Rag” is one of the classics of modern guitar picking. Such brilliant young guitarists as Don Crary, Norman Blake, Tony Rice, and Clarence White, plus an untold number of bluegrass musicians, can be described as his musical children. Watson gained public exposure through his involvement in the urban folk movement and through his appearances at bluegrass festivals. Nevertheless, he is not a bluegrass musician (as he is quick to point out to interviewers), nor is he exclusively an old-time performer, although he can perform both styles with great proficiency. Watson accumulated an immense repertory of traditional ballads, folk songs and instrumental pieces as he grew up in the mountains, but he was never totally wedded to such material, and he supplemented it with songs learned from modern commercial sources. Launching his professional career in the midst of the urban folk revival and appearing at such events as the Newport Folk Festival in 1961, Watson tailored his repertory to fit the perceived needs of the folkie listeners. He did magnificent versions of traditional songs such as “Little Matty Groves” and “Omie Wise,” but it was only in later years—particularly after his talented son, Merle, joined him as an accompanist in 1966—that audiences learned of his skills as a blues and modern country singer.

A sweet version of Dylan’s ‘Don’t Think Twice (It’s Alright)’ and ‘Make Me a Pallet On Your Floor,’ with Doc and Merle Watson and Michael Coleman (1981)Chet Flippo saw Malone and raised him in his insightful liner notes for Doc’s 1975 album, Memories, noting:

Arthel “Doc” Watson is at last getting a measure of the recognition he so richly deserves. In one sense, however, the music industry isn’t quite sure what to do with him, how to “lbel” his music, which is a rich mixture of the best the South has to offer. Two years in a row now, for example, the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences has awarded Doc one of its prestigious Grammys but it’s been in the “Ethnic/Traditional” category, which is more than a little confusing. That’s like calling Sterling Moss or Dan Gurney a good chauffeur.

Doc Watson is hardly an “ethnic” or a “traditional” performer. In fact, I’d be hard-pressed to come up with the name of a singer whose music is more American, more bedrock, mainstream American. His concerts are virtually short courses in the history of our music, for he’s drawn from and gathered together elements of field hollers, black blues, sacred music, mountain music, gospel, bluegrass, even traces of jazz. His warm voice and incredible guitar playing should be labeled--if anyone still insists on sticking him with a convenient tag--an American institution.

Godspeed to this good man.

Chet Atkins, Leo Kottke and Doc get together on ‘The Last Steam Engine Train’

Doc performs ‘Just a Little Lovin’,’ an old Eddy Arnold love song, and is then joined in fine picking by Leo Kottke.

Doc and Merle join up with Earl Scruggs and his sons on “John Hardy’

Doc Watson, ‘Deep River Blues’

Doc and Merle Watson, ‘Summertime’

Doc Watson with his North Carolina buddies Fred Price and Clint Howard (Part 1)

Doc Watson with his North Carolina buddies Fred Price and Clint Howard (Part 2) perform ‘Deep River Blues,’ ‘St. James Infirmary,’ ‘Nine Pound Hammer,’ ‘Daniel Prayed’ and ‘Mountain Dew’

From his 1975 album Memories, Doc reconstructs the Pat Boone teen tragedy entry, ‘Moody River,’ into something approaching an Appalachian murder ballad, putting his stamp on a song that defeated none other than Frank Sinatra.

His warm voice and incredible guitar playing should be labeled--if anyone still insists on sticking him with a convenient tag--an American institution.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024