‘The Heart and Soul of Stax’

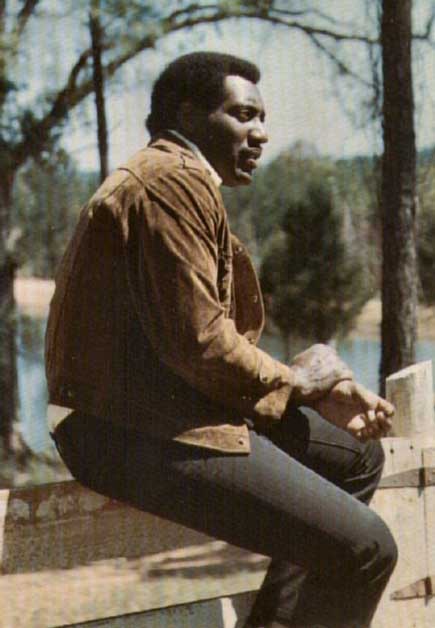

Remembering Otis Redding, the brightest star in the Southern soul firmament, on the 70th anniversary of his birth

By David McGee

When Otis Redding showed up at the Stax studio on McLemore Avenue in Memphis in October of 1926, he was there to record with the Pinetoppers, a Georgia group in which he was the lead singer. In fact, he had driven bandleader Johnny Jenkins to the session. The most important thing that happened in the studio that day came when the Pinetoppers’ unremarkable day ended early, allowing Otis to record two songs he had written, a Little Richard knockoff titled “Hey Hey Baby,” and an emotional soul ballad, “These Arms of Mine.” Promptly signed to Stax’s Volt imprint, Otis then set out on a remarkable journey that changed Southern soul music, wrote Stax’s name large in the history books, and made a legend of the man who died in a plane crash on December 10, 1967, at age 26. In June of his last year he had electrified the audience at the Monterey Pop Festival, upstaging other legends-in-the-making such as Jimi Hendrix, The Who, Janis Joplin and the Jefferson Airplane. After the festival, Otis started working with his protégé Arthur Conley. Together they re-wrote a Sam Cooke song, “Yeah Man,” into a rousing tribute to the contemporary soul masters (including Otis Redding) titled “Sweet Soul Music.” Produced by Redding, the single was released on FAME Records, sold over a million copies and peaked at #2 on the U.S. singles chart and was Top Ten across most of Europe. Later in the year, following surgery to remove polyps on his larynx, he was back at Stax to record some new tunes. One, a pensive ballad he had co-written with guitarist Steve Cropper, “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay,” was recorded three days before Redding’s death. Released in January 1968, it became Otis’s only Number One single and has lost none of its power to affect listeners to their cores with its gentle, pulsating groove; quiet, surging horns; plaintive guitar fills; and Otis’s singular voice, with its affecting quaver and mesmerizing textures of hope and despair, a certain resigned acceptance of an unspecified fate. The story that began with Otis’s first single, “These Arms of Mine,” in 1962--a modest #20 R&B hit, a #85 pop single--continues on, through the steady reissues of the man’s music (he recorded voluminously) and, more to the point, because Otis Redding’s voice will not be stilled, even in the grave. He would have turned 70 years old on September 9.

Otis Redding’s first Stax single, 1962’s ‘These Arms of Mine,’ 1962In his book Sweet Soul Music: Rhythm and Blues and the Southern Dream of Freedom (Harper & Row, 1968), Peter Guralnick summarized the impact of Otis Redding’s arrival at Stax:

If everyone who claims to have been present in the Stax studio on that momentous day had actually been there, the studio would have been packed to overflowing. There was in reality probably only a handful of people, and form most of them the session would have been no more memorable than it was for (Stax co-owner) Jim Stewart had it not been for Otis Redding’s subsequent history. He was that point very much of a Little Richard imitator and Sam Cooke admirer, though on the second side, the ballad, there is evidence of that patented quaver in his voice, the strained sincerity that was Otis Redding’s mark. Jim Stewart thought it was nervousness at first. “His voice was quavering, he didn’t really have good control over it, and you couldn’t really tell whether he was just nervous or that’s just him. Like I say, you didn’t even know he was in the studio that day. ‘Cause he was very shy at first. Later on, when he got confidence, he was a different person. “He was a very humble type person,” says (Stax co-owner) Estelle Axton, who was working in the record shop as usual but probably caught snatches of the session. “I don’t think he even had any inkling at all that would pay any attention to what he did, but as I say, we were always analyzing people for their uniqueness--and he was definitely different than anyone else we had.”

Otis Redding performs a medley of ‘Pain In My Heart’ (his third Volt single) and ‘Can’t Turn You Loose’(the B side of his 1965 single release led by ‘Just One More Day’Duck Dunn, who has sometimes been credited with playing bass on the session and played on just about every other Otis Redding record, has vivid memories of that day. “I was trying to get out of there to go to work. I was leading a band down at Hernando’s Hideaway, and if it hadn’t been, ‘Well, you won’t be back tomorrow if you don’t do this,’ I’d have just jumped up and left right then. Otis had on overalls, and I said, ‘This guy sounds like Little Richard. Who wants another Little Richard?’”

“The cat sang about two lines,” says Steve Cropper, “and everybody’s eyes just went like this--Jesus Christ, this guy’s incredible!”

“He was just like Leonard Bernstein,” says Booker T. dreamily of the myth that Otis Redding would soon become. “He was the same type person. He was a leader. He’d just lead with his arms and his body and his fingers.” Booker didn’t happen to be around when Otis’s sides were cut, but he remembers Otis’s impact, and the impact of the session, as clearly as if he were. “That place had a mind and soul of its own. It was like the music took over--or the spirit of the music took over. By him just singing, I’m sure there was some discussion about the notes and who was doing what and all that, but it was more like a happening, a natural thing.”

William Bell, who was just hanging around the studio, has memories colored by layers of legend. “Otis was an original. It was an unusual thing--everybody from the secretaries to the shipping clerks [even those functions are probably the invention of memory] started peeking in to find out who is this singing?”

Otis Redding, ‘Mr. Pitiful,’ his first Top 50 pop hit, peaking at #41 in 1964 and featured on his essential album, The Great Otis Redding Sings Soul Ballads. This live clip is cut before the song concludes.The object of all this scrutiny, both real and retrospective, was a blocky-looking twenty-one-year-old from Macon, Georgia, whose solidity gave him the appearance of someone older than his years. With his arrival Stax entered a whole new phase, and though he did not return to the studio for another nine months, it was his subsequent success that brought Jerry Wexler back to Memphis to record, that made Stax a byword in soul circles, that would eventually open up the world of Southern soul to a large-scale white audience. Otis Redding in many ways exemplified the Stax Philosophy, a vague rubric that Jim Stewart kept coming back to over the years without ever achieving much success at definition. “The Stax Philosophy is a flaunted statement in the Organization,” one publicity release declared and went on to identify it as “the basis of the Stax sound presentation” without ever really getting any more precise than that. What it all boiled down to, obviously, was a commitment to hard work, honest effort, and a team philosophy. Unlike Motown, which attempted to provide a totally controlled environment, Stax encouraged individual initiative within the context of corporate development, and Jim Stewart’s first organizing principle of business seems to have been the same as the Boston Celtics’ in basketball: to surround himself with people not simply of talent but of character, people on whom he could rely, individuals who were capable of growth. In Otis Redding he found the exemplar of these qualities. For Otis Redding was the heart and soul of Stax.

At the Stax/Volt Revue in London, 1967, Otis performs his #21 pop single from 1965, ‘I’ve Been Loving You Too Long’

At the Stax/Volt Revue’s Oslo performance in 1967, Otis offers his interpretation of Smokey Robinson’s/The Temptations’ ‘My Girl,’ a non-charting 1965 single from the album Otis Blue: Otis Redding Sings Soul

Otis performs ‘My Lover’s Prayer,’ a #10 R&B single from 1966 included on the album Complete & Unbelievable: The Otis Redding Dictionary of Soul

On the Stax/Volt Revue tour, 1967, Otis performs ‘Try A Little Tenderness,’ a #4 R&B single, #25 pop in 1967, from the album Complete & Unbelievable: The Otis Redding Dictionary of Soul

Otis, live, performs ‘Respect,’ the Redding song Aretha turned into an anthem of female empowerment. Otis’s version was a #4 R&B single, #35 pop in 1965 and was included on his album Otis Blue: Otis Redding Sings Soul

Otis interprets Sam Cooke’s ‘A Change Is Gonna Come’ on Otis Blue: Otis Redding Sings Soul

Otis Redding, ‘I’ve Got Dreams to Remember’

‘Sittin’ On the Dock of the Bay,’ video from the DVD Dreams To Remember: The Legacy of Otis Redding by Reelin’ In the Years Productions.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024