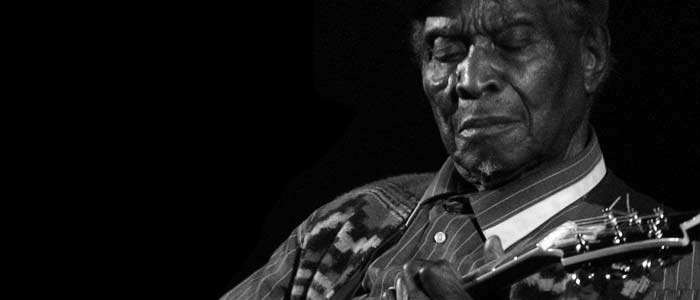

David ‘Honeyboy’ Edwards: ‘Where I do good, I stay. When it gets bad and dull, I'm gone.’Last Of The Delta Giants

From Robert Johnson’s last night alive to Barack Obama being elected President, blues great David ‘Honeyboy’ Edwards was a witness to history, and made a lasting contribution of his own with his voice and guitar

By David McGee

Born in 1915, son of a sharecropper, grandson of a slave, David “Honeyboy” Edwards lived 96 momentous years, and was both witness to and the embodiment of the best of Mississippi Delta blues in the 20th Century. His death from congestive heart failure in his Chicago apartment on August 29 was a blow both to the blues and to history, as Honeyboy was the link to an era when giants roamed the Delta making music that has grown in legend and import far beyond what any the men Honeyboy grew up and traveled with ever imagined—beyond what Honeyboy himself ever imagined, for a fact. He began playing music seriously as a 14-year-old who left his family’s home in Shaw, MS, to hobo with bluesman Big Joe Williams; eighty years later, in 2009, he was the star attraction at a pre-Inaugural party for Barack Obama at the Black Cat Nightclub in Washington, D.C., where, according to all reports, he delivered powerful versions of “Sweet Home Chicago” and Robert Lockwood’s “Little Boy Blue.” Not often at a loss for words, Honeyboy was humbled by the magnitude of the moment; after all he’d seen, all he’d experienced in coming of age well ahead of the modern Civil Rights movement, he didn’t try to hide the wonder in his voice when he said, after his set, “I never thought I’d live to see the day a black man got elected President.” Many Americans were saying the same thing, but few had the weight of the years and tribulations to match Honeyboy’s perspective.

In the Chicago Sun-Times of August 29, Dave Hoekstra remarked as to how “the aura of a shaman surrounded any given appearance” by Honeyboy. Indeed. There was something larger than life about him being the repository of so much vital history, his own and that of the other Delta blues greats he had befriended over the decades; and there was a mischievous twinkle in his eye, especially when he would play, as if he was always slightly ahead of whatever you were thinking. Legend swirled around him, too, its central feature being his eyewitness testimony about Robert Johnson’s fatal glass of whiskey—Honeyboy was there, possibly the last living witness to the legendary bluesman’s final hours.

David ‘Honeyboy’ Edwards, ‘That’s Alright.’ March 28, 2010 at the Yale Hotel, in Vancouver. Accompanied by Les Copeland (guitar) and Michael Frank (harmonica).One of the distinguishing features of Honeyboy and his contemporaries is the individuality of their playing styles. Though lumped together as Delta blues artists, Son House was no more like Charley Patton than Patton was like Skip James than James was like Robert Johnson, although they were influenced by each other and even appropriated each other’s melodies and lyric phrases in crafting new songs of their own. Listen to the first song Muddy Waters ever played for Alan Lomax at Stovall Plantation. Waters identified it as “I Be’s Troubled,” but the music is Robert Johnson’s “Walking Blues.”

In Honeyboy’s case, his sense of timing made him unique. Utterly unpredictable, it had been shaped by an apprenticeship with Big Joe Williams. Big Joe, Honeyboy told Hoekstra, “had bad timing. He played a lot of chords, but there was so much break time in the middle of them since he played by himself so much.” Blues writer Neil Slaven noted how Honeyboy ''always had a healthy disregard for meter, expanding and contracting the bar lengths of his songs at will.”

Honeyboy not only adapted Big Joe’s eccentric rhythm patterns to his own approach but delighted in confusing his accompanying musicians as to where he was going next in a song, which turned out to be pure showmanship on his part. As Honeyboy’s manager Michael Frank told Hoekstra: “Blues musicians from his generation were in one sense revolutionaries. Honeyboy was very much underrecognized as a guitar player. He was deliberate in some performance techniques because he knew they engaged the audience. He enjoyed playing so much that when he did tricks, he did them for himself as well the other musicians on stage. He loved to screw around with the very last notes of a song. He’d hold these chords and notes, look at the other guys on stage and laugh, almost to say, ‘You can’t do this, watch me.’ He never doubted himself. He liked to hear a good player but he didn’t have heroes as musicians.”

In addition to Johnson, Edwards worked with just about anyone who is anyone in the Delta blues pantheon, including Charlie Patton, Tommy Johnson, Sunnyland Slim, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Big Walter Horton, Rice "Sonny Boy Williamson" Miller, Howlin' Wolf, Little Walter, Magic Sam and Muddy Waters.

In Robert Palmer’s Deep Blues, Honeyboy described the typical arc of his and other itinerant bluesmen: “On Saturday, somebody like me or Robert Johnson would go into one of these little towns, play for nickels and dimes. And sometimes, you know, you could be playin' and have such a big crowd that it would block the whole street. Then the police would come around, and then I'd go to another town and where I could play at. But most of the time, they would let you play. Then sometimes the man who owned a country store would give us something like a couple of dollars to play on a Saturday afternoon. We could hitchhike, transfer from truck to truck, or if we couldn't catch one of them, we'd go to the train yard, 'cause the railroad was all through that part of the country then...we might hop a freight, go to St. Louis or Chicago. Or we might hear about where a job was paying off--a highway crew, a railroad job, a levee camp there along the river, or some place in the country where a lot of people were workin' on a farm. You could go there and play and everybody would hand you some money. I didn't have a special place then. Anywhere was home. Where I do good, I stay. When it gets bad and dull, I'm gone.” More such tales of the blues life as Honeyboy saw it and lived it were committed to print in 1997, in his biography, The World Don't Owe Me Nothing, which was hailed by the Boston Globe’s Elijah Ward as “the best primary document on the golden age of the Mississippi blues.”

John Hammond and Honeyboy perform Robert Johnson’s ‘Walking Blues’Edwards’ first recordings--15 in all--were made by folklorist Alan Lomax in Clarksdale, Mississippi, in 1942 for the Library of Congress. Another nine years would pass before he recorded again, in 1951, cutting “Who May Be Your Regular Be” for Arc Records as Mr. Honey. His songwriting credits include two highly regarded blues classics, “Just Like Jesse James” and “Long Tall Woman Blues”; he along with several others have claimed credit for penning “Sweet Home Chicago.” From the 1980s on he recorded regularly for a number of independent labels, with one of his finest long players being his last, 2008’s Roamin’ and Ramblin’, produced by Michael Frank, whose idea it was to recreate Honeyboy’s early guitar-harmonic duo teamings, few of which were ever recorded. To spar with Honeyboy’s guitar, Frank brought in blues harmonica virtuosos Bobby Rush, Johnny “Yard Dog” Jones and Billy Branch. The disc is rounded out with previously unreleased 1975 studio encounters between Honeyboy and Big Walter Horton, with whom a much younger Honeyboy had worked in 1935; a dynamic live set-to between Honeyboy and Sugar Blue from 1976, a couple of the Alan Lomax recordings from 1942, and Honeyboy talking about his blues life with Bobby Rush. The stark, unadorned beauty of the new tracks is as striking as the music is deeply felt by the dramatis personae. Ranging from Honeyboy’s sturdy blues moanin’ and deliberate fingerpicking over Rush’s chilling, shimmering harmonica wails in the title track to the strutting, small combo workout “Apron Strings,” to lowdown, boogie-woogie romping with Walter Horton in “Jump Out,” the mix of music is revelatory of Edwards’s varied bluesman guises. Roamin’ and Ramblin’ won a Grammy Award in 2008 for best traditional blues album, and in 2010 Honeyboy was honored with a Grammy lifetime achievement award.

‘Just Like Jesse James,’ a Honeyboy monumentOn July 17, 2011, Michael Frank announced that Edwards would be retiring due to ongoing health issues. However, the artist intended to fulfill a commitment to perform a noon set on August 29 at the Jay Pritzker Pavilion in Chicago’s Millennium Park. Fittingly, only his death that morning kept him from showing up.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024