The Turning Point

Celebrating his 86th birthday on September 16, B.B. King is the undisputed King of the Blues, recognized and beloved the world over. But in 1969, going into his seventh year on the ABC label, he was still looking for a crossover hit that would pay off artistically and financially. He was about to rebel against his label’s career guidance when he was teamed with a young, in-house producer named Bill Szymczyk who had a vision of how to modernize B.B. King without losing the essence of what had made him one of the most important blues artists of the 20th Century. The following book excerpt chronicles how Szymczyk and B.B. arrived at ‘The Thrill Is Gone’ and forever altered the artist’s career arc.

By David McGee

Ninety-sixty-eight began a momentous two-year stretch for B.B. King. He had divorced his wife and moved to New York City, where his booking agent and label, ABC, were located, and shortly after settling into a new apartment on Manhattan’s upper west side he had dumped one manager (Lou Zito) and hired Zito’s accountant friend Sid Seidenberg to take charge of his career.

“With Sid, everything started to change,” B.B. recalled. “Sid had vision. He saw way down the road. He said, ‘B, we’re going to initiate five-year plans. We’ll project ahead and see where we want to be five years from now. It’s all about expanding your market, getting your music to people who don’t know about B.B. King.’”(1)

In addition to straightening out some contractual matters, Seidenberg had badgered ABC to put more energy into treating B.B. as a crossover artist and promoting his albums as such. Critical to this strategy was finding a savvy producer with vision to work with B.B. in the studio. At ABC the artist has been working with producers that didn’t respect his songwriting or even his guitar playing--one had even brought in another guitarist to supplant B.B. on an album session. Still, B.B. had always gone along with the label’s wishes, hoping an elusive crossover hit would finally be realized; by 1969 he was bent on rebelling and insisting on producing himself, as he had in the ‘50s when he had some say in the direction of his recordings. Before he could rebel, though, his willingness to go along with the program finally paid dividends.

Unbeknownst to B.B., ABC was then harboring an in-house producer who was eager to work with him, not simply for the honor of working with B.B. King but because he also had some new ideas he thought would work to the artist’s benefit commercially and stimulate him creatively. He would take the essence of B.B. King’s music—especially the guitar—and surround it with fresh approaches to the ancient tones of the blues. His bold approach would prove vital to the realization of Sid Seidenberg’s grand plan and to B.B.’s ambition to sing the blues for as many people as his and Lucille’s voices could reach.

Bill Szymczyk had joined ABC the same year B.B. had moved to New York. His production credits included the Boston band Ford Theater, but foremost on his mind was that the label’s roster included B.B. King. ABC president Larry Newton became the target of young Szymczyk’s persistent requests to be assigned to produce the King of the Blues.

“I kept hounding Larry Newton,” Szymczyk recalls. “After my hounding him for a couple of months, he finally acquiesced and said, ‘All right, B.B.’s coming back to town next week. We’ll set up a meeting and if he says it’s okay we’ll let you do it.’ And that’s how it happened.” (2)

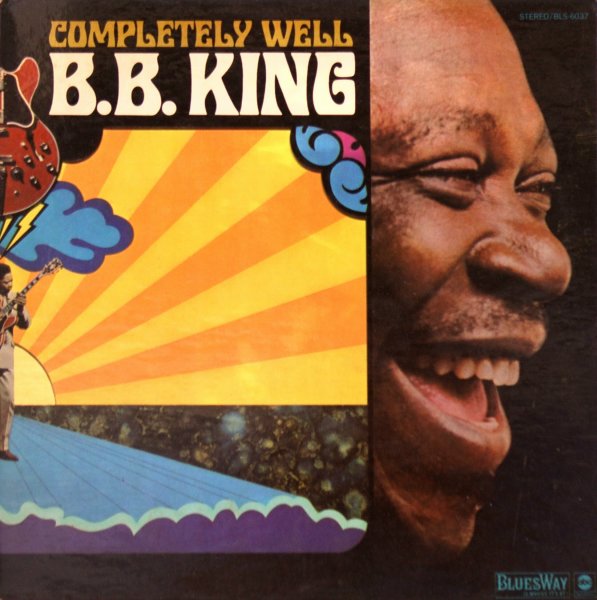

Bill Szymczyk and B.B. King in the studio during the Completely Well sessions. ‘Bill Szymczyk was a young producer and he understood me, one of those types that brings out the best in you,’ says B.B.The first Szymczyk-King long-player was 1969’s Live & Well--one side of live recordings with his road band, one side ("Well) of studio recordings, the latter with B.B. accompanied by Paul Harris on piano, Hugh McCracken on guitar, Herb Lovelle on drums, Gerald Jemmott on bass and Al Kooper on piano--a multiracial cadre of aggressive young musicians equally at home in blues, R&B and rock ‘n’ roll. For the live performance, B.B. and his band were in top form; in the studio with a group of young players in awe of him and playing their best, he responded with his best performances in years. Down Beat judged the album to be “the most important blues recording in many years.”

The good feeling of the “Well” sessions carried over a few months later when Szymczyk reconvened the same lineup of musicians (sans Al Kooper) for the album that would be titled Completely Well. The concept, as the producer explained it to the artist, was simple: “I just wanted to do a whole ‘Well’ session and [B.B.] was definitely for it.”

For the tune stack, B.B. brought in a new number, a mournful R&B balled he had written titled “What Happened”; a driving, funky album opener he co-wrote with Gerold Jemmott, “I’m So Excited”; the Jay McShann–Walter Brown blues classic “Confessin’ the Blues,” which he had covered previously as the title song of a 1966 ABC album; an exhilarating, uptempo love song penned by Maxwell Davis that B.B. was on his way to making into a classic, “Key to My Kingdom”; a sizzling collaborative effort with all his musicians titled “You’re Mean”; a Roy Hawkins song he had long admired but had never figured out how to adapt to his style, “The Thrill Is Gone”; “You’re Losin’ Me” and “No Good,” two numbers co-written with Ferdinand “Fats” Washington. “Key to My Kingdom” and “Cryin’ Won’t Help You Now” were the old warhorses of the repertoire. The former had been recorded by B.B. in 1957 as the A-side of RPM single 501 b/w “My Heart Belongs to You”; the latter, cut initially in 1956 as the A-side of RPM single 541 (b/w “Sixteen Tons”), had peaked at No. 15 R&B in its first incarnation, before a second single was issued, also RPM 451, with a different B-side (“Can’t We Talk It Over”) that didn’t chart at all.

B.B. King’s mournful R&B ballad ‘What Happened,’ from the Bill Szymczyk-produced Completely Well album (1969)In essence, Completely Well picks up where Live & Well left off, with the extended jams that made “Why I Sing the Blues” an eight-and-a-half-minutes-plus experience of bold social commentary buoyed by equally heated instrumental dialogs. At 3:18 “Key to My Kingdom” is the album’s shortest song, by a minute-plus; four others clock in at more than four-and-a-half minutes, and two of those are only seconds shy of five minutes; two songs, including “The Thrill Is Gone,” are five-and-half minutes in length; “Cryin’ Won’t Help You Now” is six and a half minutes and segues without pause into a 9:59 workout on “You’re Mean,” making for an uninterrupted 16 minutes and 29 seconds of vocal and instrumental pyrotechnics. Frequently during the instrumental passages, B.B. is shouting encouragement to his band mates, or laughing, or cracking wise (as “Cryin’ Won’t Help You Now”/“You’re Mean” fades out, B.B. can be heard joking, “Damn, what you all tryin’ to do, kill me?”). Everybody, ultimately, gets their quote in, B.B. both vocally and instrumentally.

According to Szymczyk, B.B.’s enthusiasm became part of the show of the sessions, but it was inspired by the musicians’ exuberance. “He got really jazzed by these guys because they were so aggressive and they were good, and they pushed him,” Szymczyk said. “Whereas, to be honest with you, his road band a lot of times would just do it by numbers. They'd done the song a million times and it would be by rote. Whereas the guys I put him with, they'd never played the songs, obviously, because we were doing head arrangements on the date, and they were just digging the hell out of the fact that they were playing with B.B. King, and B.B.'s getting off.”

In Alan Govenar’s 1988 book, Meeting the Blues, which is quoted extensively in Sebastian Danchin’s Blues Boy: The Life and Music of B.B. King, B.B. offers an explanation of why this and all his other sessions with Szymczyk were so productive: the producer’s hands-off approach, trusting the artist to know how the music should be made, imbued him with a sense of freedom he hadn’t experienced with ABC but was business as usual when he was signed to the Bihari brothers' Modern/Crown/RPM labels. “His ideas reminded me of the old Bihari days,” King said of Szymczyk. “He wouldn’t interfere with you while you were recording. Don’t misunderstand me. I know this was a different time, and some of us need coaching. I’m one, but only to a point. Allow me to express me as I am. Let me play as I do. Don’t say, ‘Sound like this person,’ or ‘Do you remember hearing the record of so-and-so?’ Well, that kind of attitude makes me not want to be on record because I like to be myself.

“Bill Szymczyk was a young producer and he understood me, one of those types that brings out the best in you … ” (3)

B.B. King, ‘So Excited,’ from the Completely Well album--a funky album opener B.B. co-wrote with Gerald Jemmott, who played bass on the sessions. ‘So Excited’ was not only a lively opener, but B.B.’s upbeat attitude and rhythmic phrasing elevate the proceedings to an infectious, joyous plane.Some critics have been put off by the amount of time given over to the jamming passages on this record, but time has proven Szymczyk and B.B. correct in their approach. Completely Well has aged gracefully, because the sum of its parts adds up to a more than satisfying whole. Instrumentally, B.B. has plenty of room to shine in the context of extended dialogs with other players: his single-string run in the album opener, “So Excited,” mirrors the ebullient mood of his upbeat vocal; his second break on “You’re Losin’ Me,” features a beautiful sustained note that hangs suspended in the air for a second before B.B. picks up the groove again and jets the song forward, and he repeats that feat as the song fades out. On “No Good” and “What Happened,” his melancholy soloing heightens the blue mood, and its lack of any pronounced flourishes or embellishments—leaving those more to the swaying horns and to Paul Harris’s tinkling piano commentary in “What Happened”—underscores the sadness he expresses lyrically in two ballad treatments of love gone wrong. Hugh McCracken’s feisty wah-wah guitar solo in “So Excited” adds a touch of funk to the proceedings; and Paul Harris, on organ and piano, stands out on almost every cut, whether he’s getting low-down and bluesy on the ballads or digging in to support and spar with B.B. on “Cryin’ Won’t Help You Now”/“You’re Mean,” his stylistic touchstones being both blues and honky-tonk on this discursive, syncopated journey.

Despite the number of instrumental highlights on Completely Well, in the end B.B.’s vocal performances, among his finest over the course of an entire album, carry the day. “So Excited” was not only a lively opener, but B.B.’s upbeat attitude and rhythmic phrasing elevate the proceedings to an infectious, joyous plane; no wonder the song became a staple in his concert repertoire in the years ahead—the positive message and the funky groove are irresistible. On the other hand, “No Good,” which follows the fireworks of “So Excited,” is riveting precisely for the unalloyed hurt informing B.B.’s ceaseless, intense growling as he delivers the accusatory lyrics—B.B. gives no quarter here in putting down an unfaithful woman; there’s nary a hint of mercy or forgiveness in his tone, but rage to burn. In contrast, the other slow blues, “What Happened,” is as deep a lamentation as “No Good” is a screed—the sorrow in his measured rhetorical questions at the outset—“what happened/to that beautiful smile?/the one that you gave me/any time we were face to face?”—says everything about a man utterly devastated by his lover’s change of heart. The questions persist, none designed to have an answer, but all framed to suggest the magnitude of his loss, until the blues enveloping B.B. finally overwhelms him. At the end, there is still no hope for reconciliation or even a sense that the singer is ready to move on. He is paralyzed by the blues. Again, conversely, his approach to “Key to My Kingdom” is strictly upbeat and life affirming—the best way to describe B.B.’s singing here is to say he sounds positively lovestruck as he tells of “the thrill of your kiss” and the satisfaction he gets from being with his woman.

B.B. King, ‘You’re Losin’ Me,’ co-written by B.B. and his chief collaborator from this period, Fats Washington, for the Completely Well albumApart from “The Thrill Is Gone,” the song that resonated for B.B. on this album was “Confessin’ the Blues.” His strutting vocal and the steady grooving arrangement honored the original version by Jay McShann’s redoubtable Kansas City outfit featuring vocalist Walter Brown. As a youth hanging outside Jones Night Spot, he had seen McShann and Brown perform the song (with a young Charlie “Bird” Parker on alto sax) one night, and the experience made its mark.

“All I knew was that this form of jazz mixed with blues made me happy,” B.B. said. “Hearing Walter Brown sing ‘Confessin’ the Blues’ and ‘Hootie Blues’ got me high.” (4)

(As an interesting side note, in his liner notes for Completely Well, Ralph J. Gleason pointed out that “Confessin’ the Blues,” in addition to being a big hit for McShann, was also the song Chuck Berry sang when he made his first public appearance, in an assembly at his East St. Louis high school, and that the McShann version featured Charlie Parker’s recording debut.)

That Completely Well has not always received high marks from the B.B. cognoscenti may have something to do with the final song on the album, “The Thrill Is Gone,” seeming Olympian when compared to the performances preceding it. From Herb Lovell’s first stuttering drumbeat and Lucille’s plaintive entrance with a single, wailing note, it feels like something is at stake here. The band eases in—Jemmott plucking dark, ominous notes, Harris conjuring eerie, brooding chords from the organ, McCracken filling in the gaps with robust, top-string runs—and B.B. cries out in sorrow, “The thrill is gone/the thrill is gone away,” already deep into the feeling, stretching out the word “away” to the point where it sounds like he’s near tears. After the first verse, a little more than a minute into the song, strings rise mournfully in the background, and down in the mix cellos play an “Eleanor Rigby”–like passage that is at once elegant in execution yet sinister in mood, the dark underbelly of a captivating, multi-layered string arrangement blending both light and dark textures. The light is not illusion—despite the pronounced, near-palpable pain in this narrative account of a woman whose malfeasance spelled a bitter end to a love affair, the lyric asserts the man's resolve to press on, lonely, “free from your spell” but secure enough in knowing he is a “good man” to wish his betraying paramour well as she goes her solitary way. For the final 2:20 of the album cut, B.B. plays a tart, stinging extended solo as the strings and cellos sustain their foreboding dialog, rising and falling as Lucille sings her sad refrain then backs off, while the band vamps behind him, with Harris’s spooky organ fills being the other predominant feature of the soundscape.

B.B. King, ‘The Thrill Is Gone’: the song promises majesty at the outset and delivers it throughout.In the end, “The Thrill Is Gone” promises majesty at the outset and delivers it throughout. B.B.’s soloing is frills-free for the most part, a case study in the emotional potency of a well-considered, soulful, single-string attack, and his vocal, summoned from the deepest well of his gospel heart, also is a marvel of austere embroidery, its power coming simply from an extra syllable added at the end of a lyric line, or a piercing blue note that speaks volumes about a broken heart. The band plays as a tight, restrained ensemble; and the strings, despite their prominence in the arrangement, are subtly employed, entering almost at a whisper in the first verse, ascending as the cellos gain intensity, then pulling back again for the song’s closing instrumental section. All is restraint here, whether it’s in B.B.’s soloing, in his deliberate rendering of the sad lyric, in the string section’s subtle washes of sound, or in the band’s low-profile supporting role. All of these factors working together add up to something greater than the sum of the parts, lending “The Thrill Is Gone” the incalculable, unquantifiable X factor of a classic performance.

“The Thrill Is Gone” was written and originally recorded in 1951 by B.B.’s Modern labelmate Roy Hawkins and peaked at No. 6 R&B. Arranged and produced by Maxwell Davis, Hawkins’s version begins with Davis’s screaming sax solo and settles into a straightforward, prototypical ’50s blues ballad. Hawkins’s husky, low-down vocal is buttressed by Willard McDaniel’s righteous piano accompaniment, he giving the right-hand keys a rigorous workout, and by Davis, stepping out in mid-song for a blaring solo that settles into a more introspective mode before Hawkins returns to close out the story. As opposed to B.B.’s approach to the lyric, Hawkins sounds, depending on the listener’s point of view, either utterly defeated by or emotionally disconnected from the events he describes; whereas B.B. transcends his pain and moves on with his life, dignity intact even as he is consumed by loneliness.

The original recording of ‘The Thrill is Gone,’ written and recorded by B.B.’s former Modern labelmate Roy Hawkins. ‘Something about the song haunted me,’ B.B. said. ‘It was a different kind of blues ballad, and I carried it around in my head for many years. I’d been arranging it in my brain and even tried a couple of different versions that didn’t work. But on this night in New York when I walked in to record, all the ideas came together. I changed the tune around to fit my style, and Bill Szymczyk set up the sound nice and mellow.’Roy Hawkins was a prolific writer, and his Modern singles found a home on the R&B charts in the late ’40s and early ’50s, including several in the chart’s Top Ten. In one two-year period he was Modern’s biggest moneymaker. Born in Texas in 1904, he had been discovered by producer Bob Geddins playing at a club in Oakland, California. Geddins owned a studio in Oakland and released records locally on his own Cava-Tone and Down Town labels; if he saw good sales on one of his releases, he would lease the masters to larger indies. Hence Hawkins’s path to Modern, for which he began recording, with Geddins at the helm, in late 1949. (Another of Geddins’s artists, Jimmy McCracklin, has gone on to carve out one of the more important blues careers of his time.) As if living out the despair he wrote of so often, Hawkins, then newly signed to Modern, was injured in a car crash that left one of his arms paralyzed. Nevertheless, in 1950 he had his first major hit with “Why Do Everything Happen to Me,” which is credited to Hawkins as a writer, although Geddins has claimed credit for writing the song. The single peaked at No. 3 on the R&B chart in early ’50 and had a 19-week chart run. Both B.B. (Kent single 301, 1958; reissued in 1965 on Kent as the B-side of the single “Just a Dream”) and James Brown (for Federal) later covered the song. In 1950 Modern teamed Hawkins with producer Maxwell Davis; “The Thrill Is Gone” was their first session, but after a promising start the single faltered, although Jules Bihari later claimed sales remained strong in certain markets even after the single was off the charts. Eventually Hawkins, a heavy drinker, according to Geddins, dropped out of the business. Little is known of his later years, but he did live to see B.B., Memphis Slim, James Brown, and Ray Charles cover his songs. He died on March 19, 1974, in Los Angeles County.

B.B. had never forgotten Roy Hawkins or “The Thrill Is Gone.” “Something about the song haunted me,” he said. “It was a different kind of blues ballad, and I carried it around in my head for many years. I’d been arranging it in my brain and even tried a couple of different versions that didn’t work. But on this night in New York when I walked in to record, all the ideas came together. I changed the tune around to fit my style, and Bill Szymczyk set up the sound nice and mellow. We got through about 3:00 a.m. I was thrilled. Bill wasn’t, so I just went home.

“At 5:00 a.m. Bill called and woke me up. ‘B,’ he said, ‘I think “The Thrill Is Gone” is really something.’

“‘That’s what I was trying to tell you,’ I said.

“‘I think it’s a smash hit,’ Bill added. ‘And I think it’d be even more of a hit if I added on strings. What do you think?’

“‘Let’s do it.” (5)

B.B. and Eric Clapton, ‘The Thrill Is Gone’For the string overdubs, Szymczyk called in veteran arranger Bert DeCouteaux. “Back when I was engineering other peoples' R&B stuff, he had done a bunch of things I admired, so when it came time to do a string chart, I called him immediately,” Szymczyk said. “I really liked the way he worked; I liked his charts.” (DeCouteaux would become a major disco arranger as the ’70s wore on, but his résumé also included producing and playing keyboards for Albert King, and producer credits with Z.Z. Hill, Marlena Shaw, the British pub rockers Dr. Feelgood, the Main Ingredient, and Cissy Houston.)

According to Szymczyk, B.B. had gone on the road after the session but returned for the string overdubs. “I remember him being there,” the producer said. “He loved it. He was smiling all the way through it.”

As for B.B.’s account of the session, Szymczyk offers a contrasting recollection. For starters, he claimed it didn’t happen in a 24-hour period, nor was his reaction to the song unenthusiastic. “I was ecstatic with the cut when we were doing it in the studio, so I'm not quite sure where he gets that it wasn't getting it for me, because I was over the top,” he said. “I distinctly remember throwing my hands up in the air, I was so happy, when we were doing the fade and saying, ‘Oh, this is so cool!’ And it was maybe the next day—I don't think it was two hours later, but the next day I called him up and said, ‘Look, I really want to put strings on this record.’ And he was somewhat reticent at first, in my recollection. But he said, ‘Yeah, okay,’ in essence saying, ‘You haven't fucked up so far, so go ahead on.’ I think we put the strings on maybe a week later.”

In Szymczyk’s view the success of the Live & Well and Completely Well studio sessions was no mystery: “The main thing I did was hire the right guys. That to me was the key to that whole two-album session—get the right guys and then get out of the way.”

In the studio, the producer found B.B. “real happy with everything. He was in his element, he was being himself, but he was doing it with some new, energetic guys. And I don't think we ever did more than two, three takes on anything. We'd maybe do one, go in and listen to it, make a couple of comments and then go out there and do one or two more and that would be it, usually.”

B.B. said DeCouteaux’s strings made “The Thrill Is Gone” “irresistible.” Black radio stations were on the single right away, but it soon crossed over and made pop station playlists around the country too. It had a long chart run, peaking at No. 15 pop (No. 3 R&B). It became, as B.B. said, “the only real hit of my career” and his first Grammy-winning record.” (6)

“The song was true to me,” B.B. says, noting that “‘The Thrill Is Gone’ is basically blues. The sound incorporated strings, but the feeling is still low-down. The lyric is also blues, the story of a man who’s wronged by his woman but free to go on with his life. Lucille is as much a part of song as me. She starts off singing and stays with me all the way before she takes a final bow.” (7)

B.B. King, ‘Crying Won’t Help You,’ a B.B. original from Completely WellThe success of “The Thrill Is Gone” brought far more lucrative and lasting benefits than a Grammy, though. As Charles Sawyer recounts in The Arrival of B.B. King, the single’s success resulted in a wholesale change in B.B.’s itinerary. Suddenly the chitlin’ circuit gigs were supplanted by appearances at prestigious jazz clubs on the order of New York’s Village Gate and rock halls such as the Fillmores West and East and the Boston Tea Party. College concerts became a staple of his touring schedule and, according to Sawyer, “B.B.’s regular stints in college gymnasiums from Boise to Chapel Hill solidified his new career by exposing him night after night to the young affluent whites that comprise the broad base of America’s middle class.”12 During this period of transition he also made his first appearances on network TV, with a guest shot on “The Tonight Show” (invited by comedian Flip Wilson, who was the guest host that night, although Johnny Carson later invited B.B. back several times when he was in his regular seat at the host’s desk) and on shows hosted by Mike Douglas, David Frost, and Merv Griffin. In 1970 he opened ten dates on the Rolling Stones’ American tour; in 1971 he toured Australia; embarked on a 45-day world tour in 1972; undertook an African tour sponsored by the U.S. State Department; toured Europe several times; and, according to Sawyer, experienced success “even in Israel, where the legendary Ella Fitzgerald had not succeeded.” He went all across America, playing theaters in the round to what Richard Nixon called “the silent majority”—older, white, middle-class Americans—and finally got his shot in Las Vegas, sharing a bill with Frank Sinatra (with Sinatra’s approval) at Caesars Palace. According to B.B., a weary Ol’ Blue Eyes greeted him cordially in his penthouse at the end of one night’s sets and proffered both wine and women, two items that were plentiful in the room. “I didn’t take advantage of his generosity,” B.B. said of Sinatra’s offer, “but I believe it was sincere.”(8) B.B. later appeared at the Dunes before signing a three-year contract with the Las Vegas Hilton.

A year later, Szymczyk, having relocated to Los Angeles after ABC shut down its East Coast operation, rendezvoused with B.B. at the Record Plant, for sessions that would yield not another “The Thrill Is Gone” in terms of a career-altering hit single, but an album that matched B.B. with a new cast of top-flight musicians. One, Carole King, only a year away from releasing what would become one of the best-selling albums of all time, Tapestry, was already established as one of the preeminent rock ’n’ roll songwriters of her generation. Another was veteran session man-bandleader-songwriter-arranger Leon Russell, then on the cusp of extraordinary success as a solo artist in the early ’70s. Rounding out the session was the redoubtable veteran string and horn arranger Jimmie Haskell (who had produced and arranged Rick Nelson’s great recordings in the ’50s and ’60s). The result was one of the most cohesive and stirring studio albums of B.B.’s entire career.

The most remarkable review of the single “The Thrill Is Gone” appeared in the April 2, 1970, issue of Rolling Stone, penned by J.R. Young. In typical Young fashion—no one before or since has written reviews like Young—the piece tells the story of two friends, Phil and Bud. Fraternity brothers at an unidentified Oregon school, they are on a nighttime drive when Phil reveals that once, on that very same winding mountain rode, he tuned in a radio station broadcasting,he claimed, from the late 1940s.

“Not a recording of great moments or anything like that, but the real thing,” Phil said. Bud frowned again but Phil nodded and went on, “I mean I think that somehow that radio wave or beam in its outward movement collided with something that reflected it back and somehow the car receiver picked it up and broadcast it.’”

Bud is puzzled by this, and recalls another story Phil told him: “…that someone had pictures, almost a film, of Christ on Calvary. The pictures had been discovered buried, wrapped in a parchment tube. What it was, so Phil’s story went, was a series of rabbit retinas. Someone had lined up a row of rabbits facing the cross and then chopped their heads off in quick succession. The final retinal imprint was somehow made permanent in each eye, and thus, when all the retinas were lined up, there was a pictorial study of Calvary. The story had bothered Bud for a long time.”

The review cuts to 1970, the present day, and Bud hasn’t seen Phil since 1964. But Bud finds himself back traveling on the mountain road where Phil claimed to have tuned into a radio broadcast originating from two decades earlier.

Bud pushed the button of his radio and waited for some music, but he got only static. He remembered how hard it was to pick up anything in the mountains. He slowly turned the tuning knob. Nothing but static … until slowly the dial seemed to ease into and lock on a strangely haunting tune, a lonely guitar rising somewhere from the past, and then a full and plaintive voice.

The thrill is gone

The thrill is gone awayThere was something about it, an unknown quality conjured up from the past that told Bud something, a song for long driving nights in the dark mountains, calm and clear as the lush strings rolled gently under the full white moon above and the silver road ahead. It moved on endlessly, soothing his mind, and Bud thought that, yes, here it was again, a single beam from out of the sky, vibrational energy, a wave again trapped before beginning its second stellar flight, and he found himself taking deep breaths, trying to inhale it all, the sinuous and sharp strings, the fragile tones, and that voice … that voice.

It slowly began to fade, and Bud reached for the volume and tried to keep pace with the dying sound, but he couldn’t hold it. It still fell away as Bud reached full volume. And then the sound was lost altogether. But thought he had lost the beam.

“Crap,” he muttered.

“AWRIGHT, BABY … B.B. KING AND THE THRILL IS GONE” The radio suddenly boomed at an incredible volume that almost knocked Bud’s head off. “AND WE GOWAN TO DA NEWS BABY AT TWELVE THUTY TWOO.” Wolfman Jack from San Diego and the news was today’s news, and the beam was just as powerful, not interstellar, and Bud then snapped the radio off in half a second and sat quite still for a few moments, still slightly shaken, his ears ringing.

Then he smiled and rapped the steering wheel with his knuckles. “That Phil,” he laughed. “What a card.”

- Blues All Around Me, B.B. King with David Ritz, 1996

- Interview with author, 06-20-04; all quotes from Bill Szymczyk are from this interview

- Sebastian Danchin, Blues Boy: The Life and Music of B.B. King, 1998

- Blues All Around Me

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

Excerpt from B.B. King: There Is Always One More Time by David McGee, Backbeat Books, San Francisco (2005)

B.B. King: There Is Always One More Time is available at www.amazon.com

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024