Anonymous 4 at the quarter-century mark (from left): Marsha Genensky, Susan Hellauer, Jacqueline Horner-Kwiatek, Ruth Cunningham. ‘All of us at the beginning had two feelings—independence from a single conductor and more of a collegial way of working; and also toward a different kind of presentation of the music,’ says Susan Hellauer. ‘Same songs that somebody else might present, but creating some kind of context, to take people someplace else during our shows instead of just presenting one song after another as a beautiful song.’ (Photo: Chris Carroll)TheBluegrassSpecial.com Interview

‘Let Your Words Be Clear!’

A Quarter-Century of Anonymous 4

Susan Hellauer reflects on A4’s origins and evolution, and considers the challenges in and out of Early Music (she likes barbershop quartets, too)

By David McGee

On August 3, 1986 there was no reason to expect the four women--Susan Hellauer, Marsha Genensky, Ruth Cunningham and Johanna Maria Rose--performing a Yuletide program of medieval songs titled Legends of St. Nicholas to still be at their labors a quarter-century later. And not merely at their labors but focusing the general public’s attention on Early Music to a degree unapproached by any number of excellent Early Music ensembles then extant and having formed since. They who called themselves Anonymous 4 (so named in humorous reference to the medieval composers who signed their works anonymously and by number) achieved prominence by dint of daring to challenge the norm in their field even as they honored its traditions. The honoring of traditions came in their probing the Early Music canon and revivifying ancient music in a memorable way but remaining true to the sacred intent and messages of the texts, as the quartet's haunting a cappella vocal blend reached figuratively for Heaven.

The daring comes in marshalling the bully pulpit clout of their appeal to the mainstream media and broad-based mainstream audiences alike to throw them all a curveball now and then. For example: in 2004 A4 released American Angels: Songs of Hope, Redemption and Glory, one of the most beautiful and affecting albums of any year. No Early Music masterpiece this, but rather a plumbing of the soul of primarily religious music from 18th and 19th Century America, some of it shape note singing, on fare such as “Wayfaring Stranger,” “Amazing Grace,” “Angel Band,” “Shall We Gather At The River,” “Sweet By and By"--“an enthralling musical experience (and) a spiritually uplifting one as well,” according to one Amazon reader review.

Anonymous 4, 1994: (clockwise from bottom) Marsha Genensky, Johanna Maria Rose, Susan Hellauer, Ruth Cunningham. ‘The blend comes from a flow, a unity of intent…’Much to the group’s surprise, American Angels was a juggernaut--it topped Billboard’s chart, was enthusiastically embraced by mainstream media and drew innumerable fans to their camp who would otherwise never been seen at a chant program. Having more to say in this realm, A4 returned in 2006 with Gloryland, mostly Sacred Harp songs from the 20th Century--“The Shining Shore,” “Just Over in Gloryland,” “You Fair and Pretty Ladies,” “Where We’ll Never Grow Old,” “The Shining Shore"--and instead of singing in their usual a cappella style they added superb roots musicians Darol Anger and Mike Marshall on fiddles, mandolins and guitars. It was American Angels all over again. By this time A4 had already elevated early Christmas music onto an exalted plane with no less than four programs of carols from medieval times (that number went to five with the release of last year’s Christmas album, The Cherry Tree). Not the least of the group’s achievements has come in the area of raising awareness of the truly daring music of Hildegard von Bingen, the 12th Century abbess who was a Christian mystic, author, counselor, naturalist, scientist, philosopher, physician, herbalist, poet, channeller, visionary, composer and polymath, whose legacy was captured on the A4 album The Original of Fire: Music and Visions of Hildegard von Bingen, the result of which was a full-on cross-cultural rediscovery and reappraisal of Hildegard’s life and art. A4 was hardly the first group to discover this music, but A4’s prominence spurred a Hildegard revival that continues to this day, up to and including the 2009 German film Vision, a tale centered on Hildegard’s story.

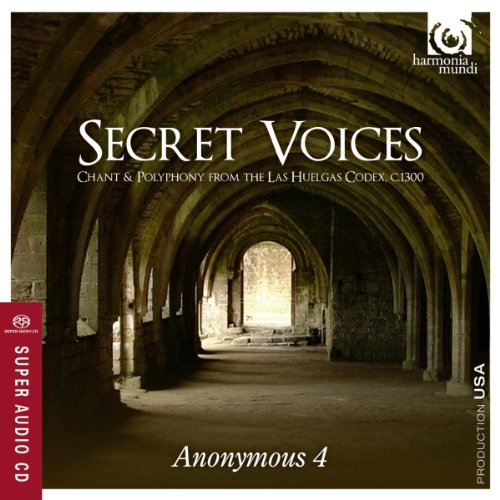

‘The Codex is interesting from a social, musical, liturgical and women’s historical perspective.’—Susan HellauerFor the latest example of A4’s singular approach, look no further than the quartet’s new album, Secret Voices, drawn from the Codex Las Huelgas, an anthology of European polyphony and monophonic Latin song spanning the entire 13th and early 14th centuries. The Las Huelgas manuscript was compiled for the nuns of Las Huelgas (a convent near Burgos in north-central Spain), some of whom were from aristocratic or royal families, all of whom had privileges unusual for women of their time--the abbesses could say mass, hear confessions and had decision making authority comparable to that of bishops and priests. Given how they could throw their weight around, so to speak, the ladies of Las Huelgas singing music that was, in the estimation of Anonymous 4’s Susan Hellauer, “virtuosic and avant-garde,” makes complete artistic, philosophical and political sense. A4 brings the Codex to life with their blended, pure tone, impeccable pitch, acute rhythmic sense and, not least of all, in their intense emotional engagement with the deeper stirrings of the soul expressed in the texts. In a transcendent performance their ethereal voices join together to illuminate the nuns’ inner lives—the strivings, the longings, the sense of discipline and order but also of individuality—so as to make the ladies of Las Huelgas real and relevant to our time.

Secret Voices is Anonymous 4 at its most haunting. Consisting of 23 pieces of lengths varying from under a minute to nearly five-and-a-half minutes, the program is organized to reflect the liturgical day the ladies of Las Huelgas experienced, or might have experienced, based on all available knowledge. Thus the sequencing according to the convent’s daily devotionals: First Light, Morning, Mass, Evening, Night, sections comprised of sequence, conductus, motets, discant, Kyrie, Gloria, Sanctus, Benedictus—plainchant, hymns, doxologies, the components of Mass: as Susan Hellauer writes in her liner notes, “…we have created a ‘day’ of music in honor of the Virgin Mary, and have also included songs with texts that refer to the monastic life of the nuns themselves.” That is to say, Secret Voices breaks free from the medieval divine office’s dictate that specific prayers be chanted at prescribed hours of the day to include music revealing of the nuns’ monastic and spiritual lives both. Indeed, in the opening sequence in First Light, Virgines egregie, the translated Latin lyrics reveal the the nuns’ raison d’etre: Once you guarded the lily of chastity/for the son of God, whom you pleased;/you wished to be the temple of the holy spirit/and thus you fled from touch and marriage bed. The Morning discant Fa fa mi/Ut re mi, a hexachord exercise, on the other hand, speaks to the nuns’ higher calling: Sing out these and other such things/you cloistered virgins,/golden nuns:/you are fitted for this/because you were born to cultivate polyphony [the wisdom which the holy ones have handed down]—an interesting charge since the Cistercian order prohibited women from singing polyphony. But the ladies of Las Huelgas were no ordinary nuns.

Anonymous 4, 1996: Benedicamus trope: Congaudeant catholici, from the album Miracles of Sant’Iago: Music from the Codex Calistinus, selection of chant and polyphony taken from a fascinating 12th-century manuscript that includes not only music but also sermons, stories, legends, and an informative travel guide to the pilgrimage routes through France and Spain. The collection originated in France, but since the late 12th century it has resided in the famed Cathedral of Santiago in Compostela, Spain. The album cover shown here, Miracles of Compostela, is Harmonia Mundi’s 2008 reissue of the original album.Then there are puzzlers, abstruse but provocative, such as the Benedicamus domino of the Mass, Belial vocatur, which contains one oblique reference to Mary (as Simeon) but otherwise seems a pointed tirade aimed at Satan, who is referenced by one of his Biblical names: Sly cunning is everywhere/and his name is called Belial/He is lord and master over/the newer art of war./Happy is the going out/that knows no error;/beautiful is the coming in/that bestows love./He who was held in the arms of Simeon/is the lord of all things:/nature marvels/at this [divine] co-mingling… If this sounds as if Secret Voices boasts a variety of musical styles, well, it does, further indicating the richness of the Codex Las Huelgas. The rondellus Benedicamus domino à 3, which closes the Mass section, reflects an English influece, yet has never been identified with any English source. In an interview with the classical website ariama, Ms. Hellauer points out that the Las Huelgas convent was conveniently located for the nuns to be able to absorb influences from far and wide: “Remember, the convent was on the road to Compostella,” she says. “It was a big travel stop, so people would come by routinely to go to Compostella. People still go there and we did a concert across the street from the shrine, and night and day people were going in and out; it was like the subway at rush hour. It was like that in the Middle Ages too. The convent was on the crossroads of Europe. They were powerful women there with the power to do things in the convent that ordinary nuns couldn’t. They also had friends in high places, so they had a lot of the secular hits of the 13th century but transformed with new texts into music they could sing devotionally and liturgically. The Codex is interesting from a social, musical, liturgical and women’s historical perspective.”

Much to the amusement of the women of Anonymous 4, their greatest mainstream acclaim has come since announcing their 2003-2004 season as their last as a full-time recording and touring ensemble. American Angels and Gloryland are part of A4’s post-retirement triumphs, as is last year’s Yuletide gem, The Cherry Tree, as is Secret Voices. At this point the four Anonymous women are in select company: the only other artist whose Christmas catalogue boasts as much breadth and depth as A4’s is Frank Sinatra; the only other public figure to experience such a bountiful resurgence after hanging it up is Michael Jordan. Moreover, Martha (raised in California, lived for awhile in New York, now resides in California), Ruth (from Millbrook, NY) and Susan (a Bronx, NY, native) have enjoyed the 25-year run together. Of the original core four, Ruth left in 1998 and was replaced by Jacqueline Horner-Kwiatek (from Monkstown, Northern Ireland), who remains with the group; in 2008 Ruth returned to the A4 lineup when Johanna moved on to work solo.

‘It’s mystical without being religious’: chant camp ‘for people who love to sing chant,’ at Stanford University’s Memorial Church, led by Anonymous 4. Interview with Susan Hellauer.From the start Susan Hellauer, with her Master’s in music history from Queens College, City University of New York, and doctoral studies in Medieval Musicology at Columbia University, has been Anonymous 4’s resident historian--not group historian, mind you (although in a way she is that) but the point person who researches not only the etymology of the music in each new program being considered but also the social/cultural/political/religious issues informing the music. Authoritative and insightful, her research is published in slick, multi-lingual liner booklets accompanying each new album. For this 25th anniversary salute to Anonymous 4, it seemed fitting to talk history with the resident historian--the history of A4 and of the challenge Secret Voices posed and how it was answered. From her liner notes, you expect to encounter a woman of keen intellect and sharp insights, and she does not disappoint on those counts. Her strong, assertive responses bespeak an active, quick mind, but her ease in laughing at her own foibles and some of the professional dilemmas she encounters in the stuffy world of musicologists is strictly the stuff of roll-with-the-punches pragmatism in regards to her chosen career. Talking to Ms. Hellauer is most certainly an educational experience, but it’s also a hoot.

***

Susan Hellauer: ‘There has to be a real shared passion.’25 years ago Anonymous 4 got together in the wake of Johanna’s work with a musical ensemble participating in a medieval culture workshop at a monastery. Where did the other three of you come from to form the original Anonymous 4? Were you also at the workshop? Were you all friends? How did the original core four come together?

Friends and colleagues. The world of early music was and still is a small world. So everybody sort of knew each other from freelancing in the same Renaissance choirs and churches that concentrated on Early Music. So people just ran into each other and you ended up singing on the same jobs and all that. I think the impulse was partly from that, but also, I have to say, as you get older, as you mature in the field of Early Music, there’s a real tendency, the longer you work with conductors, to start to think about interpretation; to start to think about contextualizing things or how to put a show together rather than “a string of my favorite pieces about springtime.” There’s a better way to present music. I think all of us at the beginning, independently, had those two feelings—independence from a single conductor and more of a collegial way of working; and also toward a different kind of presentation of the music. Same songs that somebody else might present, but creating some kind of context, to take people someplace else during our shows instead of just presenting one song after another as a beautiful song. That’s good; there’s nothing wrong with that, but there’s a better way. That’s not something somebody had to tell us we should think; it sort of came with it. And I’m sure lots of other musicians who start little groups have the same kind of feeling. How many groups start every year? Thousands and thousands and thousands. And how many take root, where the roots really go down and something grows? Maybe a dozen out of those thousands, every year. So there has to be a real shared passion.

The Legends of Saint Nicholas was the first project you did together. Were you considering yourselves a dedicated group at that point and looking to move forward into other projects, or did you think Legends of St. Nicholas might be it and everyone would go on and do what they would do?

You know, that’s funny. I think we did consider ourselves a group. That came really fast. The first thing we did was a church service on August 3, 1986. I still have a little manila folder with the music in it. It’s a variety of medieval pieces that would fit in with that church service. I guess it was summertime and the choir was off, but a couple of us sang in the choir, so we said we would do something for that day. We did, and it really caught fire. The feeling was one of independently taking the music, deciding how it goes, deciding how to present it, how it’s going to sound, how our voices are going to interact, as a collegial project, without one person saying, “Okay, you sing this, you sing that, not too fast, not too slow.” Nobody was squelched. Nobody had to defer to anybody. The only deferring that might happen is if somebody has a special expertise in the repertoire. Then you might defer to that person for contextual information or other things about the text or about the use of it. But in terms of how it goes, how we sing it, that’s up to all of us.

Anonymous 4, Lullay: I saw a swete semly syght, from the group’s second album, and first Christmas album, On Yoolis Night (1993)Legends of Saint Nicholas later became part of your extensive holiday catalogue. When I spoke to your colleague Marsha Genensky last year, I told her the only other artist who’s in your league in terms of the depth of the Christmas catalogue is Frank Sinatra. That’s the company you keep at Christmas time.

That’s so funny! My goodness. Because we tend to concentrate on English music very often, we fell in love with the sound, first. The English loved Christmas; they really adored the whole concept of Christmas. So we’ve got three English Christmas records. Christmas was sort of a feast day all over Europe, but it’s really in the British Isles that Christmas became almost as big as Easter. Probably, early Christianity, the people who promulgated it, were very, very smart and put feasts on top of existing Pagan feasts. Not just in the years two, or 20, or 40, or 200, but ongoing, into the Middle Ages, feasts were moved around. The Feast of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary in the early Middle Ages was in the wintertime and it was moved to August 15, which was fabulous because it’s a harvest feast called Lamas in England. So you have these things, wherever that Feast might have been a higher or a more important Pagan feast, the Christian feast that gets pasted on it will definitely take on some of that importance. I’m not an anthropologist so I can’t tell you exactly but you can feel the excitement in the music in the British Isles that you don’t quite get as much of—or not as much repertoire—on the Continent.

So Nicholas was the first real program that we put together where people would come and hear us sing. We would print programs and we had little stories in it, we did narrative readings, even acted out a little play—I can’t even believe we did that—but it was part of our exploration of how we were different, how we could be different from everybody else. Contextualizing was always our ace in the hole that set us apart from other people. We didn’t record Nicholas right away. We actually waited awhile. The very earliest programs we tended to change a lot as we went along, as we figured out what worked better, what didn’t work as well, where we wanted to focus. The earlier programs we tended to record a little bit later. The first two we didn’t record right away. I think it was the third program, An English Ladymass (1993), that we recorded first.

Talk about contextualization! Your liner booklets are critical to helping people understand where the music came from and the society it came out of. Each time I read one I wonder were you studying this history before the group even got together? Or did you take it up after the group formed?

Yes, it’s very important. I have a Master’s in music history from Queens College, City University of New York, and I also have an MPhil, which is how Columbia University politely says “didn’t quite write the dissertation” (laughs), in Medieval Musicology. In fact, when I was at Columbia I made a big hoo-ha about the fact that the Medieval Ph.D. courses you had to take did not include anything about literature, about Latin palaeography, about Provençal poetry, art history, all of these things that are and were back then so crucial to a musicologist. A musicologist studying a manuscript has to know about the illumination. Some of the most famous research articles and works and dissertations in musicology have dealt with things that are completely extra-musical, like the quality or type of paper, the type of illumination, the liturgical context, the language that those little notes in the margin are written in. So there’s so many extra-musical things that I militated for—I was very strong in saying, “You have to allow people to do this.” They finally let me out and said, “Shut up already and take the course. We’ll count it.” Now, I was just speaking to someone from Columbia who said, “Columbia has this really amazing program and really hard because you have to take art history, you have to take Medieval poetry, Latin palaeography, they don’t make you just take music courses all day." I said, “Oh, very interesting.”

Countless students have followed in your wake, and look what you’ve done to them.

And good for them, because they’ll have more weapons at their command when they go out there to deal with the actual source material. It really broadens you. I know I should finish the Ph.D., and my 89-year-old mother, bless her heart, says, “You’re never going to be Dr. Hellauer, are you?” And I say, “Well, mom, I think it’s a little too late.” But I never regretted anything. I had a family, I had to go to work—I was a computer programmer for twelve years in the telecom industry, I’ve been around the block in that way in work and in life and I really know what a privilege it is to go to the library. To do the research. To do the kind of work Anonymous 4 does. I think it’s just Heaven on Earth. For me, anyway, for how I was trained and my inclinations. I love to be in the library, but it means nothing to me if it’s not brought to life.

Anonymous 4, Edi beo thu hevene quene, a polyphonic song from the group’s first album, An English Ladymass (1993)When you look back over the past quarter-century, can you say you’ve achieved what you had hoped for the group? What’s your take on 25 years of Anonymous 4 history?

You know, I’m very grateful to have made a modern, middle class living out of it. First of all, that’s amazing, just in terms of Early Music performance. We all do other things, too. We teach privately and in schools and Ruth does music and healing, so we’re not one hundred percent full time. Back in 2003 we decided to stop being full time and to stop developing programs at the rate we were developing them. We sort of took a break from that. On the other hand, then, right then, unbeknownst to us, American Angels came around. The recording company said, “You want to do what?” I said, “I want to take a break from making recordings. We have an expert, Marsha, in American traditional music, I heard some [William] Billings and some shape note music on a radio program and said, “I think we could do that. I think we’d sound good doing that, actually.” But I had no knowledge. I came up with the name of the program and the idea--that was it—and then handed it over to Marsha. The recording company goes, “Ohhh, oh, okay, if you insist.” So in 2002 we made that recording, didn’t think that much about it, hoped somebody would buy it, and it’s our only recording to have gone to Number One on the Billboard chart. Still, whenever we sing some music from it, I get this big, happy smile on my face, and I hope we can do another one in the future, a third in a series of American projects. And then, because that went to Number One, we had to support it. People really wanted it. We were happy to go out on tour and sing it, and then do another American project [Gloryland, 2006]. So our original plan was upended by the unexpected success of American Angels. We couldn’t say, “We’d rather stay home,” because our original plan, what we originally set out to do, was to bring little-known or unknown repertoires to a large number of people. Now, our first concert had twelve, maybe fifteen people, but you still had the feeling that you wanted people to hear things they hadn’t heard or some things that they had heard but in a new way, a new sound, a new context, and to take our always very individual, very different sounding voices and put them together and make them blend not by forcing ourselves to sing the same vowels or all that kind of barbershop stuff, but to have a unity. I shouldn’t disparage barbershop because, honestly, I can’t believe what they do! A good barbershop group actually floors me. But you know, I mean in terms of making sure every vowel is exactly the same and the declamation being identical. To us the blend comes more from a flow, a unity of intent, that we all feel the same about the musical lines and where they’re going. So that’s what creates the blend, not the sound of our voices. And you know, that’s something that maybe people don’t hear that often, in terms of a blend.

We were in Guadalajara a couple of days ago. There was a travel advisory and not all of us were doing cartwheels of happiness about going to some place where things are being blown up. But we went. There was a big fiesta out in the square for the end of the Pan American Games, a big mariachi band, but they sort of quieted down when we started singing in this beautiful theater. It wasn’t packed—because there was this huge festival going on at the same time--but there were a lot of people there and there was a family in the front row with two little kids who were just beaming from ear to ear through the whole show. I looked at them and said, “That’s it. That’s why I’m here.” That’s a reason to get on the plane and make sure nobody’s shooting at you. To touch a life—what else is there? It’s hard to resist the temptation to do that. We don’t make a million dollars, don’t always stay at first-class hotels, don’t fly first class, but we’re fine, it’s fine. There’s really no complaints and the reward to me is incalculable.

Anonymous 4, ‘The Cherry Tree,’ from 2003’s Wolcum Yule. Its 19 selections include traditional folk melodies and texts, some of which date back to the Middle Ages, interspersed with fitting selections by contemporary composers including John Taverner, Benjamin Britten, and Peter Maxwell Davies. Andrew Lawrence-King plays Irish harp, Baroque harp, and psalteryI remember the 2003 announcement of the group retiring at least from the road. But since then you’ve released about five albums and in fact have done some of your best work. I was joking with Marsha in our interview last year about Anonymous 4 being the musical Michael Jordans. You’re into a really active retirement.

But if it hadn’t been for American Angels it would have been different. Harmonia Mundi has never said to us, “Now it’s time for a Hildegard record.” Or, “We need another Christmas record.” They’ve never said boo to us about what we should or should not do. And when something is a hit and they’re doing well, we have a perfectly decent recording contract—I’d say it’s average and a little plus—but nobody buys CDs so it doesn’t really matter. But they’ve done the right thing and we needed to do the right thing for the recording even though they thought, “Hmmm. Really? What?” It was important to do that, and to follow up with Gloryland was a real natural thing.

Using Secret Voices as an example, how does a recording project start? Did you do the research that we read about in the liner notes thoroughly before you presented it to the other three? What’s the timeline on your finding this material, researching it and presenting it to the rest of the group and actually starting to rehearse and getting into recording?

Some of our projects are a single manuscript project, where we focus in on a single manuscript. This one’s very famous and I’ve known about it since graduate school days. It was discovered accidentally in the early 1900s by the Cielos monks over in Spain, who were looking for chant manuscripts and came upon this thing with a mixture of one-, two-, three- and four-part music. But why did the nuns have it? Were they singing polyphony? So it always had that intrigue about it, and I knew about it. In fact, we did some pieces from it when we were just starting out. There’s some great music in there—it’s like a compendium of the best thirteenth century music, like an anthology. So we did pieces from it but I never wanted to do a program from it because I didn’t want us to get typecast as a women’s music group. Very early on we avoided Hildegard and we avoided this Las Huelgas manuscript, which is associated with a convent and women singing polyphony. Now it wouldn’t be such a big deal, but back then, in the mid-‘80s, we might have heard, “Oh, it’s women’s liberation choir!” Nothing wrong with that; it’s fine—ask my husband! But it’s not what I wanted to do with the group—I had that feeling very strongly and the others did too. But I just didn’t want to get pigeonholed, didn’t want to be “they’re the women who sing women’s music.” We started deliberately by avoiding it. But it was always in the back of my mind and the rest of them always knew that one day, at one time, we would do a program of it. It’s such an unusual and well-known manuscript source in medieval circles, it’s been recorded a lot, by all sorts of fabulous groups. We really had to do something different. I actually used a discography, when there was a choice, to try to pick the pieces that had not been recorded. So I picked the theme of Mary and life in the convent before I actually looked at the discography—those two threads really hold it together, it’s like a liturgical day in the musical framework, then pieces in honor of the Virgin Mary is the thematic frame. So they work together like that. There’s a natural progression, which is always important to us in our programs, that you start somewhere and you go someplace. People should feel like they’ve been on a journey with us.

So we all really knew about this for many, many years, right back to the beginning, but it kept taking a back seat, partly because it’s been recorded a lot, partly because it’s so woman connected. But a new facsimile came out in 1999 or the early 2000s, and it was so beautiful. I was more or less pretty much dissatisfied with the rhythmic transcriptions that existed already in the scholarly literature and editions. The rhythmic way of transcribing struck me as wrong and I knew I would have to put my head down and re-transcribe everything. I was fortunate enough to correspond with a musicologist who wrote a companion edition to that Spanish facsimile, an English scholar named Nicholas Bell. I just wanted to run my ideas of the rhythmic meaning of the notation by him, and lo and behold, thank goodness, he had the same idea. Though he didn’t do any transcriptions, he had the same idea, that the notation is late, around 1300, and when they’re writing down pieces from 1210 or 1225, or when they’re writing down monophonic music, the notation doesn’t have the same meaning as it does for later pieces. With that, because I’m not a full-time musicologist—I know where to go, I know how to do this stuff, I know how to transcribe—when there’s a question like that, a fly in the ointment, I’ll consult with somebody. Musicologists now, as opposed to 25, 30 years ago, are way more generous with their time, their thoughts, their ideas. They want to hear this stuff played, whereas a long time ago musicologists, if it wasn’t published yet, would be very keechy about what they thought. They just wouldn’t tell you what they really thought because they didn’t want us to say, “We want to thank Nicholas Bell for his advice and help,” only to have some other musicologist say, “You told them what?! You idiot!” They get very worked up over what I would call—I won’t say nothing—but very small details. Of course it’s a small world, a closed system, a tight community of people who study and think for a living. I do that partly for a living, but the other part is I try to make it come to life as if it could not have gone any other way. People should have the feeling while we’re singing that this is the way the music went and it could not have gone any other way, even though I and we all know that we have no idea. There’s fragmentary information about vocal style, tempo, ornamentation, vocal tone. There are scraps of information in treatises about that but not much. It’s not all from one place, either—this guy in Spain said this, this guy in England said that. And also, if you’ve never heard western music and you read a review of a concert of western music, you would have no idea what that sound was that the person’s talking about. You have to have a sonic reference point to unlock a verbal discussion of musical sound.

Anonymous 4 today, Gloria: Spiritus et alme, from the Mass section of the new album, Secret VoicesThis fragmentary evidence, is it in the form of musical notation?

These are statements in musical treatises. Sometimes it’s poetry, sometimes it’s a traveler’s description of what she or he heard some place, things like that, so that it goes from technical in a treatise to using words like “a pure, clear sound should be used” and things like “you can slow down a little at the end.” There was a big fad in I think it was the ‘70s or ‘80s in Renaissance and Baroque music of having no ritards, so everything just sort of hit the wall! (laughs) Because there are fads and fashions in performance practice. We’re too close to really see it, but there are fads and fashions in performance practice itself. So people think, I know how Bach wanted this to go: it should be this many people playing at this really fast tempo and whatever. And yet there are all these technical elements, but what about the spirit? What about the love and the emotion behind it? There’s sooo much we don’t know. I’ve read a lot of what people have had to say about how to sing, or how singing sounds, and it adds up to a big, fat goose egg. The only thing consistent is that your words should be clear for the various repertoires of medieval music done in public. Let your words be clear! And that’s why we don’t sing that high. We don’t go up into the high register that often when there’s enunciation to do, because then you start noticing the pear-shaped tones or whatever and not what we’re trying to tell you.

And how do you find the spirit or the soul of the song? So many people I know who like Anonymous 4 remark about how soulful the group sounds. Obviously you get there.

Partly you have to discover both the personality of the program you’re putting together, the personality of each individual piece, and what role that plays within the larger dramatic musical “thing” you’re presenting. It’s like a family with all different people in it: they all contribute, and they have genetic similarities, but they also have different quirks and meanings and uses and ways of doing things. So with each piece, you unearth its personality. Now, we don’t know how it went, so the text is our main guide, and then certain aspects of the internal speed of the notation. How small are the smallest notes? How fast can you sing those small notes? Are they ornamental small notes or are they meaningful small notes? Are they decorative filigree, or are they actually structural? There’s a lot of analysis that goes on—chord harmonic analysis, although you don’t really say that in medieval music but, you know, the speed of the chord changes, as we would call them in modern parlance. The harmonic speed; the melodic surface texture has a lot to do with it; and the text. Then its place in the program. And then, when you find that personality—you mentioned Frank Sinatra. When he got a brand-new song, he would not allow himself to hear the tune until he had lived with the lyrics for a long time, maybe a week or two, and learned it as poetry, learned it as a completely verbal expression of something—some emotion, some need, some feeling, some event—and then put the music to it. That’s a lot of how we work.

Anonymous 4, ‘Sweet Hour of Prayer,’ from 2004’s chart topping album, American Angels: Songs of Hope, Redemption & GloryBut remember, we have recordings of the Paul Whiteman Orchestra playing “Rhapsody In Blue” before Gershwin wrote it. In fact, it even occurs in a movie called The King of Jazz. And if you watch and listen to them play, it has this slanted 1920s jazzy tempo, really bouncy, really fast, not a lot of loose-limbed blues like we have now—totally different. But here we have a recording of what was actually in the composer’s mind. Why don’t we always play it like that? Because the audience is part of your performance. You can’t discount them, can’t put them behind a soundproof glass so they watch you like museum pieces. They’re in it; they’re in it with you. And if you don’t bring them toward you, it’s just a museum artifact. So we use our modern intuition. We use tuning things, where we try to use just intonation as we can, but you know, the thirds and sixths, maybe they’re tempered, I don’t know. We try not to get insane about that. We’re very insane about our fourths, fifths and octaves but less insane about the imperfect controls. We don’t want people to notice that we’re doing something, except communicating the text and the spirit of the particular piece that they’re hearing now.

You mention in your notes as well the ongoing dispute as to who actually sang the Codex you drew on for Secret Voices. You’ve come to believe the nuns themselves sang it. I’m guessing that’s not just a hunch on your part but that something in the texts tipped you off as to this possibly being the case. What is your evidence for believing the nuns sang this repertoire?

Well, in the little piece we sing near the beginning of the program, Fa fa mi/Ut re mi, it says in there, “Sing out you golden nuns. You would be wrong to spurn the practice of this kind of music because you were born to sing polyphony.” Now, some of the really challenging Notre Dame pieces in there have been recorded many, many times, so we kind of stayed away from that area. The nuns probably sang these simple little duets and things, but they could not have sung the really complex stuff. That's not saying they were too stupid or unable to learn how to do it; there’s also the craftsmanship, the artisan stuff. These nuns were aristocrats, and to sing church liturgical polyphony is the job of a trained singer who is a professional, not an aristocrat. The divide is between the aristocratic and the professional class, so it might have had something to do with that as well. Not just “women could not have possibly done this.” So it’s colored in shades of more than just black or white, that they did or they didn’t. It’s not quite that clear. But I didn’t want to open yet another can of worms in the program notes, because I really don’t know. However, when you think about the aristocratic mindset in feudal times, in the Middle Ages, you can see that certain things are just not done. Whereas in the Renaissance aristocrats were very much expected to do music; not professionally, but on a professional level. It was an accomplishment, rather than something only a hired hand would do.

Also you refer to this music as “virtuosic avant-garde music of its time.” Virtuosic I understand from the complexity of the vocal parts, but why is it avant-garde for its time?

Some of the motets that are in there, especially, have tremendous complexity. The distance between the slowest and fastest parts. The joy of mensural notation right around 1300, the big excitement about it among musicians, composers, was how many different levels of speed you could show and make interact at the same time. So the earlier polyphony, you might have only one really slow part that was like a drone and then the other parts moving along. As you get through the 13th century, you start getting pieces that have wildly different speeds in gradations among the parts. We did a couple of pieces like that. That’s more a new thing, those later motets. Some of the more songful laments take chant composition—really a late, late, late dated chant composition—to fabulous heights. People think of chant as being done once polyphony comes in, but there’s really wonderful monophonic laments written in 1300. Once you get to 1400 you stop having that so much. It’s old-fashioned antique in a way but it also has great powers of expression—of course Hildegard did things like that, but she was special—she was the most fabulous dead-end music has ever known. Mainly it’s in the motet composition, very avant garde, and some of the conductus, several of them have duple rhythm, which would have been quite rare at that time. That’s a way of pushing the notation, which was really invented for triple-triple-triple, all triple, or maybe compound, like 6/8 or 12/8, but actually it’s something like 2/4 meter that’s not found that often. The last big piece we did have quite a bit of that.

Anonymous 4, ‘Shall We Gather At The River,’ from 2004’s chart topping album, American Angels: Songs of Hope, Redemption & GloryAnd what about these ladies of the Las Huelgas retreat? Your note say their numbers included members of the royal families, and they also had privileges beyond what churches were granting to most women at that time and possibly even now. Organized religions have had a famously difficult time granting privileges to the women in their congregations. How much authority did the women of Las Huelgas wield in their world?

Mainly that authority would have devolved upon the abbess and maybe a couple of other people. But actually fulfilling some liturgical functions such as hearing confessions, making rulings on canonical law without consulting men—which was like, “oh, my goodness!”—and usually in the early days of the Middle Ages a female institution would never be all by itself. It would also be joined to a male institution.

Do you remember the movie that came out last year, Vision, about Hildegard von Bingen? It’s fantastic. I saw it and actually did a little lecture after it for a local showing. It’s German. It’s very much worth watching if you love medieval music. It’s not mainly about music, but there is some music in it. You can see that she had to be subordinate to the male, the abbot, of the abbey she was connected to, until she took her ladies and went someplace else, through great hardship. But that idea of always being joined to a male institution…if there were really difficult things you’d have to go to the abbot, but the abbess at Las Huelgas had privileges akin to those of a priest—they could even take confession.

Official trailer for Vision (2009), the story of 12th Century Benedictine abbess Hildegard von Bingen, Christian mystic, author, counselor, naturalist, scientist, philosopher, physician, herbalist, poet, channeller, visionary, composer and polymath. Directed by Margarethe von Trotta, starring Barbara SukowaSome of those privileges actually stayed in place into the 19th Century, I believe, because they were members of the royal family or high nobility. There were nuns that really were lower classes and they probably did the grunt work. The ladies, they retreated from the world, as many women did after they had had their children. Their husbands had died or they were extraneous to the family—they already had, you know, eight daughters to marry off. But Hildegarde was the tenth child in her family, so she was tied to the church. And she was one of those lucky shots—you went in as a child and said, “This is it. This is where I want to be.” There’s a motet in Love’s Illusion [note: Love’s Illusion: Music From the Montpellier Codex 13th Century, a 1994 album by Anonymous 4] the text of which goes, “I’m a young girl of 15/my little breasts are budding as they should/I feel the first pangs of love under my little belt/curse him who made me a nun!” So there’s the other side, which was very real. People were put there and this is where you go. On the other hand you’d live a longer life, probably, than women on the outside, who very often would die in childbirth.

Fascinating stories. I could ask you dozens of questions about the songs, but one in particular stands out for me as at least lyrically different from the others. I realize you have much more material to choose from than what we hear on this disc, but this one—Benedicamus domino: Belial vocatur--is specifically about Satan, identified with the Biblically resonant name. Its lyrics are fascinating and unlike others we find in this program. For instance, Satan is described as the “lord and master over the newer art of war,” and it contains this epigram: “Happy is the going out that knows no error; beautiful is the coming in that bestows love.” What do you make of this in the Codex?

I really don’t know. (laughs) That was very difficult to translate. I don’t usually do this, but I actually consulted a couple of other translations and I don’t understand what they were talking about. The translations were actually more obscure than the Latin! But you get this kind of thing—it’s probably some sort of massaging of a Biblical text somewhere and not by a Bible scholar. You look into the Concordance of the Bible and try to find things. It didn’t occur to me, but it’s probably a couple of references jammed together. This is one where we went a little away from Mary—she’s present when Jesus is in the arms of Simeon, so it’s got a little sideways reference, but it’s such an unusual piece and so laden with dissonance that we had to put it in there. And it’s four part; there’s not that many four-part pieces. It really attracted me. There’s so many Benedicamus settings in this Las Huelgas Codex because eight times a day they would say “Benedicamus domino Deo gratias”—“Let us bless the lord, Thanks be to God”—there are many, many settings because it occurs so much. So I wanted to show you how many kinds of Benedicamus dominos you find in there.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024