TheBluegrassSpecial.com Interview

The Rich Life of Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind

Marking the 75th anniversary of the publication of Gone With the Wind, authors John Wiley Jr. and Ellen F. Brown craft the definitive story of a literary phenomenon

By David McGee

In early April of 1935, Harold Lathem, editor in chief of Macmillan Company, one of the dominant and most prestigious book publishers in America, journeyed from his Manhattan office to Atlanta, Georgia, one of several stops on a southern scouting tour in search of new authors. Local writers hustled to finish manuscripts for Lathem’s inspection. Arriving with an open mind, hoping to learn more about the region as well as meeting its writers, Lathem was perhaps hoping to find the literary equivalent of what the Victor Talking Machine Company’s Ralph Peer--like Lathem, based in New York City--had discovered on his own southern scouting trip in 1927, namely the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers, who became major stars and ushered in the modern era of country music.

Lathem knew no Atlanta or Atlanta-area authors personally, but he was aware of one, thanks to the enthusiastic reports he had received from Lois Cole, an associate editor at Macmillan, who had come to work in the New York office after serving as the office manager of the company’s Atlanta branch. In Atlanta, Cole had formed a fast friendship with a former reporter (and still occasional freelancer) for the Atlanta Journal Sunday Magazine named Margaret Mitchell. Mitchell had resignedher position with the Journal after suffering an ankle injury--health calamities were a constant of Mitchell’s life--that had put her on crutches, making it difficult for her to go out and research her stories and do interviews. Cole not only knew Mitchell as a talented writer who had dabbled in fiction (notably with a draft of a Civil War-era novella called Ropa Carmigan concerning the life of a reclusive woman from a privileged family whose life had taken an unfortunate downward turn), she knew Mitchell had another, more ambitious and nearly complete novel set in the Civil War and detailing the effect of the war on the lives of her fictional Georgia families, notably the O’Haras and the Hamiltons. When Cole met Mitchell in 1927, the author had been working on her novel in fits and starts for a year; two years later, it was essentially complete, save for a first chapter (Mitchell wrote the last chapter first, so she would know how her characters’ fate, and wrote other chapters as inspiration struck, and in no specific order, on no defined schedule). It was untitled, and the manuscript pages, though organized into chapters in manila envelopes, were scattered around the Mitchell home--a couple of those envelopes even found a utilitarian purpose in propping up a couch with uneven legs.

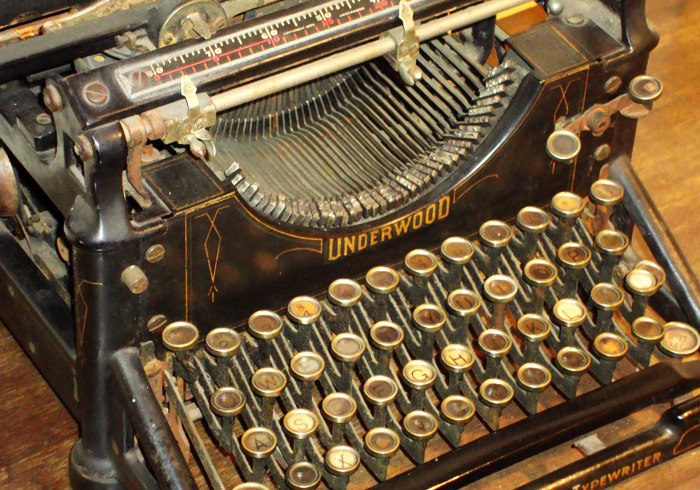

Margaret Mitchell with her novel, Gone With the Wind. (Photo: William F. Warnecke/Newscom)Apart from her husband, John Marsh (her second husband; her first marriage, in 1922 to Berrien Kinnard “Red” Upshaw had ended in divorce two years later, and in 1925 she had married Marsh, a tall, bespectacled, former English professor and newspaperman from Kentucky who was then employed in the publicity department of the Georgia Power Company; he had also been the best man at the Mitchell-Upshaw wedding), Mitchell spoke of her work in progress to no one, not even family members who would inquire about it. When her friend Lois Cole visited one afternoon, Mitchell, seated at her desk typing away on her Underwood, quickly threw a towel over her work to keep Cole from seeing what she had written. After Cole moved to New York, she kept in touch with Mitchell via U.S. mail, urging her to send the novel to Macmillan, always to be rebuffed by the author. Cole’s importuning niggled at Mitchell enough that she went back to her manuscript and began tweaking it here and there, revising and reworking several chapters towards the middle of the book that she felt were stifling the action.

On November 22, 1934, however, Mitchell and Marsh were injured in an automobile accident. Mitchell suffered a back injury that confined her to bed for three months; even after becoming ambulatory again in the spring of 1935, she was in such chronic pain she could not sit at her desk and work. Her unfinished novel would have to wait.

During Lathem’s visit to Atlanta, he met with Mitchell twice on April 11, at a luncheon and later for afternoon tea. On both occasions Lathem inquired about the novel Lois Cole had told him about and whether Mitchell would let him appraise it for publication. On both occasions, Mitchell demurred, saying the book was in no shape for a professional evaluation, but if she ever finished it she would be sure Lathem was the first to see it.

Returning home after her second visit with Lathem, Mitchell was suddenly seized by the urgency of the moment. After consulting with her husband, who encouraged her to let Lathem see her work, Mitchell hurriedly gathered up the envelopes from their various resting places under the bed, in the closet, under the couch. The chapters were not numbered, some envelopes contained multiple drafts of the same chapter, there was still no first chapter, but Mitchell did what she could to organize the material into some semblance of order. In lieu of a first chapter, she hastily wrote a synopsis of the book’s opening scenes. She rushed to Lathem’s hotel, describing her appearance upon arrival as “hatless, hair flying, dust and dirt all over my face and arms and worse luck, my hastily rolled up stockings coming down about my ankles.” Finding Lathem sitting on a couch with a small mountain of manuscripts next to him, Mitchell presented her still-untitled novel after extracting a promise from Lathem that he would not share it with anyone else, adding that he should take it now, before she changed her mind about turning it over.

Back at Macmillan headquarters in New York, Mitchell’s manuscript steadily gained advocates, starting with Lathem (“this woman has something” was his first take on it) and Lois Cole. Lathem sent the manuscript to a highly regarded Columbia University English professor who was employed by Macmillian as a freelance reader; he praised the book as “breath-taking” and “magnificent,” and urged Lathem to tender a contract to the author immediately. Lathem then met with Macmillan president George Brett, Jr. and his editorial council to press the case for signing Mitchell. Convinced, Brett gave Lathem the go-ahead to offer Mitchell a contract with a $500 advance and a percentage of the book’s profits. Only then did Lathem, and Macmillan, learn that whatever insecurities she had as a writer shy about showing her work to others, Margaret Mitchell had an iron will when it came to protecting her rights and financial interests as an author.

Margaret Mitchell’s Underwood typewriter. (Photo: Margaret Mitchell House)Her manuscript itself, though, was revealing enough about the woman’s character. Having been born in 1900, only 35 years after the end of the Civil War, Mitchell had grown up hearing stories from people who had either actually fought in the war or were related to Civil War veterans. Making extensive use of the public library research facilities at her disposal, she assiduously checked the most minute details of the conflict, not only pertaining to the major battles, but down to the material used to make flags and uniforms, even the weather conditions on certain days pinpointed in the story. She read diaries, government records, firsthand accounts of life in antebellum Georgia, letters her grandparents had written to each other during the war, articles her father and brother had written for the Atlanta Historical Bulletin. In a note to Harold Lathem, she emphasized her insistence on her accounts of the war being “air tight so that no grey bearded vet can rise up to shake his cane at me and say, ‘But I know better.’” The point of all this research was not only historical accuracy but also inspiration--she wasn’t one to take notes but rather to absorb the essence of the war years in her effort to recreate, in fiction, the mood and temper of the times. In a Junior League magazine profile of her published in 1936, Mitchell said the only notes she took were in the middle of the night when an idea came to her in her sleep and she was too lazy to get up and go to her typewriter.

Margaret Mitchell: the only notes she took were in the middle of the night when an idea came to her in her sleep and she was too lazy to get up and go to her typewriter.One of many aspects of the novel that impressed the Macmillan staff was Mitchell’s sure command of atmosphere and pacing. As haphazardly as the original manuscript was organized, the story was there, complete, and a mood was captured at the start and sustained throughout. All agreed that once the first chapter was in, little more needed to be done in the way of editing and rewriting--the copy was virtually clean, in publishing parlance.

Small wonder: raised in a family of lawyers who prized clear, unambiguous writing, Mitchell said “I sweat blood to make my style simple and stripped bare. I’m sure if I had evidenced any style in early childhood, it would have been smacked out of me with a hair brush!” Normally one given to colorful, descriptive language, Mitchell labored to remove all excess verbiage from her manuscript--if it didn’t advance the story or was not essential to character development, it was excised. After whittling down section after section, she would put her novel away for a couple of months, then revisit it and, with fresh eyes, find more obvious passages to delete.

As the manuscript got into the fast-track production pipeline in New York--everyone at Macmillan was certain they had a big winner on their hands and wanted to get it into the market quickly--a couple of other issues came to the fore. A title, for one. Lathem had suggested Another Day as the name for Mitchell’s novel, but Mitchell suggested Tomorrow Is Another Day or Tote the Weary Load, though she feared the first had already been used as the title of another novel (it had), and that the second was “too colloquial.” Bugles Sang True, None So Blind and Not In Our Stars were other titles Mitchell suggested and promptly rejected. She remembered an 1891 poem by English poet Ernest Dowson titled Sum Qualis eram Bonae Sub Regno Cynarae (or, “Cynara”) and its opening line: “I have forgot much, Cynara! gone with the wind.” By coincidence, the phrase appeared in Mitchell’s novel, in a scene when her principal female protagonist, originally named Pansy O’Hara, returns to Tara, her family’s plantation, after fleeing Sherman’s wanton destruction of Atlanta. “Was Tara still standing?” Pansy wonders. “Or was Tara also gone with the wind that had swept through Georgia?” On a list of 22 possible titles, Mitchell indicated Gone With The Wind as her favorite by placing a star next to it, along with a note that she would agree to anything Macmillan liked.

For another, Mitchell suggested her main character lose the name Pansy, because it was also slang for homosexual and might be misinterpreted in certain parts of the country. She had run across the name Scarlett in Irish literature, and in fact had used it as the maiden name for Pansy’s grandmother. After consulting with Lois Cole, who approved of the Pansy-to-Scarlett transformation, Mitchell gave one of the most famous characters in literary--and subsequently in film--history the name all the world would soon know.

Lathem approved both the change of Pansy to Scarlett, and Gone With The Wind as the title, and urged Mitchell to finish up her edits. Published 75 years ago this month, in May 1936, Gone With The Wind, carrying an unprecedented three-dollar price tag, created a national sensation. By the end of December one million in sales had been rung up. Margaret Mitchell won a Pulitzer Prize, a National Book Award and was nominated for a Nobel Prize. Hers is the best selling novel of all time. The 1939 film adaptation starring Vivien Leigh as Scarlett O’Hara and Clark Gable as the louche blockade runner Rhett Butler assured the book its pop culture immortality. Over the years critics have decried its depictions of African-American characters and its soft pedaling of the true nature of the Ku Klux Klan, but even against charges of being “a profoundly racist novel,” as historian James Loewen describes it, Gone With The Wind has found a new audience, worldwide, every year since 1936, and its most devoted fans--the “Windies”--show up en masse to celebrate every notable day in Gone With the Wind (book and movie) history.

There was much more to Margaret Mitchell’s story than the writing and publishing of Gone With The Wind. In 1937 Mitchell and her husband learned a Danish newspaper had been serializing the novel absent any contractual permission to do so or payment of royalties for use of the text. At that time in domestic publishing history, international royalties were literally a matter of small change. For Margaret Mitchell, it was a matter of principle, not money. For the rest of her life--she died in 1949 after being struck by a car while crossing Peachtree Street in Atlanta--Mitchell made it her cause to secure proper accounting and royalty payments for her international sales, and to track down and punish the foreign publishing houses that were bootlegging her book (the pirates were rampant, and sophisticated, too--Mitchell herself appreciated the care and beauty that went into many of the pirated foreign editions’ designs but she wasn’t going to let anyone steal her book, plain and simple). Her triumphs in this realm--which continue to the present day, with the Mitchell estate being especially vigorous in prosecuting Gone With The Wind bootleggers--established the right of all succeeding American authors to profit from their international sales, indeed, even to have a foreign market for their books. Margaret Mitchell created that too.

From December 1939: (from left) Olivia DeHaviland (Melanie Hamilton in Gone With the Wind), Jock Whitney, Margaret Mitchell and her husband John Marsh at the Gone With the Wind premiere.This is but a summary of the story behind the story of the novel. In Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With The Wind, authors Ellen F. Brown and John Wiley Jr., both based in Richmond, VA, have written the definitive biography of the book. A more fitting tribute Mitchell’s classic novel could not have: Brown and Wiley left no stone unturned in researching Mitchell’s life and her manuscript’s journey from its various resting places in the Mitchell-Marsh home to the offices of Macmillan to international best seller to the basis for a beloved movie of legendary status itself. Theirs is not a Mitchell biography proper, but the authors have uncovered fascinating details about Mitchell's life and work that have either escaped her many biographers, or been misstated by others in their rush to aggrandize the Mitchell legend.

As for the story of the book itself, it simply has never been told in such detail, and for that, as Ms. Brown will readily attest, credit goes in large part to her collaborator. A self-professed Gone With The Wind fanatic, John Wiley Jr. has spent the better part of his life, since seeing the movie at age 10, to collecting all things Gone With The Wind and researching the life of its author. For 25 years the publisher of the authoritative The Scarlett Letter newsletter, he has gained the unqualified trust of the Mitchell estate. When he and Ms. Brown decided to write their biography of Mitchell’s book, the estate opened its vaults to the authors, making them privy to long-sealed documents and personal papers otherwise unavailable to any other authors. Like Mitchell’s own prose, theirs is straightforward, unembroidered, direct and focused on moving the story forward with a minimum of side trips, and no psychobiographical speculation or florid language. A worthy achievement indeed, Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With The Wind is an essential addition to the Gone With The Wind literature--after Mitchell’s novel, the most essential addition, in fact, unless somewhere, some time, documents unknown to the Mitchell estate or to Gone With The Wind historians and archivists pop up with verifiable facts that alter the storyline as we know it now. It seems an unlikely turn of events: in the years since 1936 the most significant Margaret Mitchell discoveries have been but two in number: in 1995 the Road To Tara Museum unveiled a novella written by Mitchell, in a month’s time, when she was 16, a tale of love and honor set on a South Pacific island and titled Lost Laysen, the most interesting aspect of it being the female protagonist, Courtenay Ross, whose feisty, independent nature seems a model for Scarlett O’Hara; and this past March the Pequot Library in Southport, CT, revealed it had possession of the final four typescript chapters of Mitchell’s novel, which apparently were given to the Library in the early 1950s by one of the Library’s major benefactors, George Brett, Jr., the president of Macmillan who in 1935 had directed Harold Lathem to offer Mitchell a contract for Gone With The Wind. This is the closest the public will likely ever get to seeing Mitchell’s manuscript, as the original was burned after Mitchell’s death, at her request and by her husband, save for a few pages preserved in a vault in Atlanta and never to see the light of day unless another author comes forward contesting Mitchell’s authorship of her famous novel.

How did the Pequot Library learn of its historic Gone With The Wind treasure? The diligent Ellen F. Brown had queried the library about the Brett collection and whether its many foreign editions of Gone With The Wind contained author-to-publisher inscriptions.

In the following interview, Ms. Brown and Mr. Wiley discuss their personal and professional journeys into the world of Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With The Wind and the resulting invaluable book. Frankly, my dears, they do give a damn.

***

John F. Wiley, Jr. and Ellen F. Brown, authors of Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind.‘She’s a Good Role Model for Remaining True to Yourself’

John Wiley Jr. and Ellen F. Brown discuss their journey into Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind

You two have done something remarkable with this book. In formulating my questions, I realized if I asked you every question I wanted to ask, I’d end up writing a book about the book about the book. So I’ve tried to narrow it down and do justice to your work without keeping you on the phone for hours and hours. There is, as you know better than anyone, an extensive body of Gone With The Wind literature. Where did the idea to do the book come from? Did one of you propose it to the other? And how did you determine there was a need for this book?

ELLEN: The way it came about is I am freelance writer, and I was assigned to write an article about John’s collection of Gone With The Wind memorabilia. I was not a Gone With The Wind person; didn’t have any particular interest in it, other than I had seen the movie and of course thought it was great. And I was just so fascinated by why John had spent so much of his life collecting Gone With The Wind. He’s one of the world’ preeminent collectors of Gone With The Wind memorabilia and Mitchell memorabilia. I was just so taken with what was so exciting about Gone With The Wind that somebody would devote their life to it in this way. Right after we met--we both happen to live in Richmond--we got to talking. It was just a few minutes into it and he had me hooked. I hadn’t realized that Gone With The Wind, the novel, had lived this very rich life before the movie ever came out. It was a Pulitzer Prize winner; won the National Book Award; Mitchell was nominated for a Nobel. John had these amazing stories about the history of the book. I said to him, “Where’s the book on that? I want to read more.” He said, “Well, there’s biographies of Mitchell. There are compilations of her letters. There are books about the movie.” But no one had ever written a book about the book. I said, “You’re crazy if you don’t do it.”

JOHN: And I said, “I have a real job, I don’t have time to do it.”

ELLEN: So I kept badgering him about it, and he finally called me one day and said, “Let’s go to lunch.” We sat down at lunch and he said, “Let’s do this together.” I jumped at it.

The search for Scarlett O’Hare and Ashley Wilkes on screen: actors, including Tallulah Bankhead, Susan Hayward, Paulette Goddard (who has the inside track on the job, owing to producer David O. Selznick’s fondness for her), Lana Turner, Jeffrey Lynn, Melvyn Douglas and others test for the role of Scarlett O’Hare. Includes scenes not in the final script.John, since Ellen mentioned your near-lifelong interest in Gone With The Wind, what has fascinated you about it that you’ve devoted so much energy to it over the years?

JOHN: It started, of course, when I saw the movie and read the book. It just grabbed me.

You saw the movie before you read the book?

JOHN: Saw the movie at the age of ten. And then decided I wanted to read the book, and I liked it even more than the movie. I’ve always been a collector of some kind. I think people either have the collecting bug or they don’t. I guess to relive the experience I started collecting. Then I was especially fascinated by the book and I started buying different editions of it--a paperback, a hardback, a motion picture edition. Then when I realized there were foreign editions of the book, that opened up a whole new world!

You needed a storage room, right?

JOHN: Absolutely!

ELLEN: He had a whole house of it.

JOHN: I have about 800 different editions of the novel.

Including a first edition?

JOHN: Oh, of course. Of course. In a dust jacket.

ELLEN: Signed first edition.

Vivien Leigh and Hatty McDaniel test for their parts in Gone With the WindWhen did you start your newsletter, The Scarlett Letter?

JOHN: Actually, it ran under a different name for a while, but I started the original newsletter in 1987. We’re pushing 25 years.

It’s a subscription-only publication, right?

JOHN: Yes. I’m an old-fashioned newspaper man and I like print things. It’s a print newsletter. I asked subscribers a couple of years ago and the vast majority came back with, “No, don’t make it online! We want to read it. We like to hold it. We can take it with us.” I was happy to hear that so I can stick with the way I do things.

So once you agreed to move forward, how did the research break down? Who was in charge of what, and how did you actually write the book?

JOHN: Our first trip to gather material was to the University of Georgia, where Margaret Mitchell’s papers are--

By the way, John, in your collecting, had you made contact with the Mitchell family?

JOHN: Yes.

ELLEN: That’s a big part of how we got permission to do the book. To access the Mitchell papers, to copy them, to quote from them, the estate exercises control over all that. I’m not sure anybody else on the planet would have been given the permission we got other than John, because the estate thinks the world of him.

JOHN: Well, thank you.

ELLEN: You know that’s true.

JOHN: I hope so. I’ve always been obviously above-board with them and over the years they’ve grown to trust me. We started at the University of Georgia, where the Mitchell papers are--I think we spent a week there together--then we sort of split from there. I went back several times, Ellen went to New York for the Macmillan papers, and she did a remarkable job. She’s an expert on the Internet, and I’ve told people she should have been a detective. She tracked down so many people--children and grandchildren of people related to the book; the Brett family, who were the publishers of Macmillan; Lois Cole--that was just a huge find, her two children. She was a friend of Margaret Mitchell’s, worked at Macmillan, played a huge role. Kudos to Ellen for that. I don’t know if you saw the story recently about the typescript pages they found at a library in Connecticut. They found those because of Ellen’s inquiry.

Margaret Mitchell inscribed some foreign editions to George Brett, the publisher of Macmillan. We tracked those to a library in Connecticut. Ellen called and asked if we could get copies of the inscription. They sent them, they weren’t anything exciting--“To George Brett, Best Wishes, Margaret Mitchell.” But, as they were going through their inventory list, they realized they had something. They weren’t quite sure what it was. So I think it was late last year they called--

ELLEN: I think the beginning of this year. It was right after the book came out. I had called them about our release.

JOHN: They announced that they had rediscovered the last four chapters of Gone With The Wind, the typescript that Margaret Mitchell had sent to Macmillan from which the book was typeset. It contains hand-written corrections by Margaret Mitchell and by her husband, John Marsh.

There were two manuscripts: the manuscript she turned over to Macmillan, which they sent back to her after she signed the contract. She then sort of rewrote it and got it in order and retyped it. This retyped version is what these chapters are from. But of course they have “My dear, I don’t give a damn,” “Tomorrow is another day”--I mean if you’re going to find four chapters, those are the ones you want to find.

ELLEN: The exciting thing about the discovery was that it had long been thought that the document had been burned. Either Mitchell had done it during her lifetime, or her husband had done it after her death. People thought we would never see this. To have this pop up was a real exciting discovery.

Scarlett listens in on the men ginning up their enthusiasm for war, with Ashley Wilkes and Rhett Butler both throwing a damper on the proceedings.Was that just a myth about it being burned? Or was it really burned?

ELLEN: I think the vast majority of it was burned. The real mystery is how these four chapters ended up in George Brett’s hands. I like to think Mitchell pulled them aside and gave them to him, but there’s certainly no transmittal letter in the Macmillan files, or in the Atlanta files we’ve seen. Maybe he just held onto them, maybe they got lost in the shuffle along the way. But I do think the vast majority of the rest of the manuscript was burned. The only thing we know of that might still exist are some chapters that her husband had pulled aside and put into a safe deposit box in Atlanta. They’re supposed to be held there indefinitely in case anyone challenges her authorship. But nobody’s ever seen those, so we don’t know if they exist.

JOHN: Well, actually, I have confirmed that they are still in that vault.

ELLEN: Oh, when did you hear?

JOHN: Last week. I asked that question and was told, yes, they’re in the vault.

So the manuscript was purposely burned?

JOHN: Yes, in 1938, when she wrote a will, she specified she did not want her papers put on display, given away, anything like that. But she re-wrote her will ten years later and didn’t go into that detail. She just said she wanted her papers to go to her husband, John Marsh. She died in 1949, the papers went to him, and he decided--based on, I’m sure, the conversations they had had--he knew her wishes--that she did not want those seen. So he made notes that he burned most of the original manuscript, most of the typescript, notes, that kind of thing. But he did specify a few things he set aside in this envelope.

Including portions of the original manuscript?

JOHN: Right.

So there is some little bit of that remaining?

JOHN: Right. I don’t think we’ll ever see it, unless someone seriously challenges her authorship, which I don’t think anyone can do. Marsh also says if it’s never needed, it’s eventually--eventually--to be destroyed unopened. Legally I don’t know what “eventually” means.

I hate to hear that.

JOHN: That’s how she felt. Who was it? Leona Helmsley left ten million dollars to a dog. I think that’s kind of stupid, but it was her money and if that’s what she wanted…

The Carol Burnett Show’s classic Gone With the Wind parody, with Carol Burnett as Scarlett, Harvey Korman as Rhatt Butler, Carol Lawrence as Sissy, Tim Considine as Brashley Wilkes and Dinah Shore as Melody Wilkes. Part 1.

‘I saw it in the window and I just couldn’t resist it’--The Carol Burnett Show’s classic Gone With the Wind parody, part 2In your extensive research--and your source notes and bibliography suggest how extensive it was--did you uncover anything about the book or Margaret Mitchell’s story that contradicts what has been the standard bio and story about the book? Had something entered the Gone With The Wind legend that you found to be demonstrably untrue or mythologized all out of proportion to what really happened?

ELLEN: I think we could go all day on that! That’s been the real fun of this project. John’s been researching this his whole life--the process of creating this newsletter has been 25, 30 years of research he’s been doing. So that was invaluable. But I had a lot of catching up to do, so I had to go back and read all the books. There were so many contradictions in the different stories that I really wanted to tune those out and just focus on the original source material when we developed our chronology of events. So what I did was literally go through page by page, day by day, and developed a chronology of the life of Gone With The Wind. Then when I went back and started comparing it to the other books, to see what was out there, I couldn’t believe the differences. I remember calling John, it seemed like every day, or emailing him and asking, “Is this true? I read something that said this. How can that be true when the documents say this?” It seemed like every day there was some new discovery or something contradicting something in some way. I don’t say that to be critical of previous biographers. I think they had limited information available to them; we had so much more than they did, especially because of things we were able to get off the Internet.

JOHN: We made a conscious decision at the beginning: use what’s already been written as background, but if you want to know the date of something or what really happened, go to the original source material. Because it is so easy in transcribing to miss a date, misread something, that kind of thing. We did not include things that we did not have the original document to back up.

ELLEN: I think there may be three places where we quote one of the other books, because there were instances of documents that no longer existed and we had to rely on their statements of what those documents said. Just to give you a few examples of how this happened, for instance: if you’ve read our book you know there are two Brett brothers, Richard and George. One of the previous biographers appears to have thought they were the same person, and treated them just as George and quoted from Richard as if he were George and came up with this very negative view of Mitchell’s relationship with him. When in fact Mitchell and George got along famously, especially toward the end of her life. It was Richard who didn’t think much of the Mitchells and had a lot of conflict. That biographer and another one had also freely quoted letters from Mitchell’s husband as if Mitchell had written them. And Mitchell and her husband were very much on the same team on a lot of issues, but not on all of them. Some of the letters her husband had written, he had a very short fuse in some ways and would rip off a pretty stern letter very different in tone from what Mitchell would have said. If you read it coming from a man, you kind of got it; but reading it as if a woman had written it made her sound awful. We went back and read the letters and went, “she never said that--it was John.” The key difference between our book and the other books is that you get a very different picture of who Margaret Mitchell was.

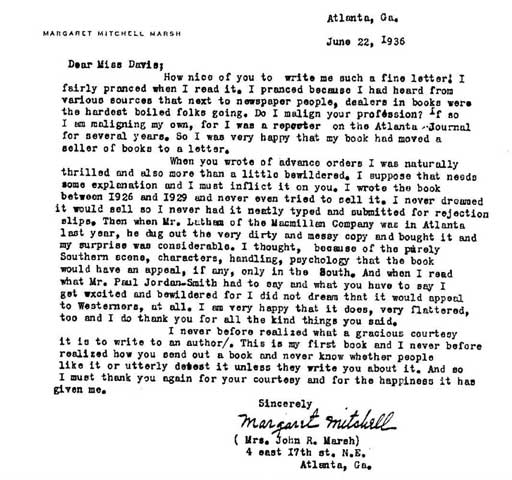

A letter from Margaret Mitchell on June 22, 1936, thanking a book dealer who had written her with effusive praise for her first novel.Does anything in particular stand out to as a particularly outrageous story about her that has become legend over the years but in fact is not true?

ELLEN: The Lathem story, John?

JOHN: Yeah, that’s really not so much about her, but I think that’s a key. Again, going back to Ellen tracking down the children of Lois Cole. They had been approached before by other biographers. They said their mother was a very private person and never traded on her friendship with Margaret Mitchell, so they had always declined. But I think between Ellen’s charm and the subject of our book, they really liked the idea that we were doing what we called a biography of the book. So they agreed to share some things with us. It really sort of re-wrote the whole discovery of the manuscript section. Traditionally, Harold Lathem, the vice president of Macmillan, who was in Atlanta, has gotten all the credit--he found the manuscript, he read it, he did all of this. Well, as it turned out, he did take possession of the manuscript in Atlanta because Lois Cole had told him and had laid the groundwork for it. I’m not criticizing him; he was on a scouting tour, but he had many other places to go. He shipped the manuscript back to New York very early; Lois Cole is the one who took it home, got it organized, wrote a fifteen- or twenty-page summary and critique of it. So she is the first one to have read it. And she’s the first one to have said, “Wow, this is something special.”

So finally she gets her proper historical due in your book.

JOHN: Right.

ELLEN: I think telling her story is one of the things we ‘re most proud of in this book. It was a real glass ceiling kind of thing.

You mentioned while Margaret Mitchell was still reporting for the Atlanta Journal--she may have been freelancing at that point--she wrote a draft of a Civil War-era novella called Ropa Carmigan. Is that among the manuscripts that no one will ever see, or have you actually seen it?

JOHN: That was among the things destroyed. She had sent it to Macmillan--whether on purpose or accidentally--when she turned over the manuscript of Gone With The Wind. They liked it but said, “Let’s concentrate on the novel for now,” and they returned it to her. It was unfortunately one of the things destroyed. In 1995 a novella she had written as a teenager surfaced and was published. It was called Lost Laysen, and it was set in the South Seas. She had given it to a beau, and years later his son, quite elderly, found it among his father’s possessions. They ended up publishing it. I think she would be horrified.

ELLEN: I was going to say she would be horrified.

A deleted scene between Scarlett and Melanie in Gone With the WindHow long did you research before you got down to writing, and once you did start writing, who did what? How did the process work?

ELLEN: We were writing the whole time. You know how a non-fiction book proposal works in that you have to write sample chapters as part of the book proposal? So we had written several chapters before we did any research. Needless to say, those chapters did not make it into the final manuscript. So we really were writing the whole time and researching side by side. In fact we were researching up until the day the manuscript was submitted to the publisher. We kept finding new things, kept expecting to get to the point where things would be duplicative, but I don’t feel that has ever happened. In fact, people are still contacting us and sending us things. It’s a side by side process here, the research and the writing. The way the writing worked was, John focused on the beginning and the end, I did the initial drafting of most of the middle, then we shared drafts and sat down together and went through it word by word, literally at my kitchen table, reading it out loud to each other, trying to fine tune the voice.

JOHN: I got to know Ellen’s family very well.

ELLEN: It’s funny, we’ve had this almost mystical feeling about this book at times, that it was meant to be, that we were meant to be. That we live in the same city is really what enabled this to happen. If we hadn’t both lived in Richmond I don’t know if we could have done this.

Margaret Mitchell seems like a most ambivalent novelist. On the one hand, she didn’t even keep her work in progress in any kind of order--you write about the manuscript going into manila envelopes as it was finished, and then those envelopes sometimes serving a utilitarian purpose in the home--propping up a couch with a short leg, for instance. On the other, she worked hard at crafting the right atmosphere for her story, and at keeping her writing simple and direct, saying “I sweat blood to keep my style simple and stripped bare.” What do you make of an approach that sometimes seems so casual and at others so deadly serious? What was driving her to tell the tale?

ELLEN: That’s one of the myths that we busted, I feel. Mitchell said many, many times, “Oh, I didn’t pay any attention to this. I never thought in a million years anybody would read it. Oh my goodness!” The whole deer-in-the-headlights, this-is-all-too-glamorous kind of thing. And many people took her at face value and said she was just a housewife who had done this novel for fun and wow, look at her fabulous overnight success. But if you really dig deeper into her correspondence, to people who knew her, she took it deadly serious. As she said, she sweat blood and tears in making her writing the best it could be, and that’s why it took her ten years to write it. If the whole situation with Lathem hadn’t come forward, she might have taken another ten years revising it.

JOHN: In a way she was an insecure writer, I think it’s fair to say. She wondered would people like it? Would people really get it? I think all writers are--you just hold your breath that a reviewer doesn’t catch you in a mistake or tell that you totally missed the boat. But I think she was a little concerned, but absolutely, she was a professional writer. She knew what she was doing.

And what about her research into the Civil War? She didn’t consider it a “Civil War novel.”

JOHN: It was a homefront novel; it certainly wasn’t a Civil War battlefield novel. And she wanted to make sure all the facts were correct, but she also said while she was writing it she just sort of, “Okay, I think this is what great aunt so-and-so told me,” and she put it down. Once it became clear it was going to be published, the rubber hit the road, and she had to go back--she brags that she found numerous references supporting source materials for practically every fact in the book. I think we mention that she was writing around “What time would they have planted this particular kind of cotton or buckwheat?” Things like that, which most people might say, “Oh, well, that sounds good, I’ll throw it in there.”

What kind of connections did she have with actual Civil War veterans? What had been her exposure directly to them?

JOHN: Of course, born in 1900, it was only 35 years since the end of the war. She certainly grew up with people who had fought in the war, and both her grandfathers and grandmothers had lived through the war. Sunday afternoons, sitting on the laps of these people, back in the day when children were seen and not heard, you just listened. So she gathered a lot through that. As a child she would play on the fortifications around Atlanta; she said she would go horseback riding with some of the old vets, who would get into arguments about who did what when. She really absorbed that. In fact, when the movie premiered, two or three Confederate veterans, then in their 90s, attended the movie. They were around through her whole growing up.

Screen tests for the Melanie Hamilton character, Gone With the WindHave you encountered any occasions where her characterizations of the time of the war in that book have been criticized by Civil War scholars as inaccurate?

ELLEN: I haven’t. Have you, John?

JOHN: Take Reconstruction, for example. The whole general, historical feeling about Reconstruction has changed over the years; history is always revised. But when you look at the facts she had in the ‘20s and then in the ‘30s when she was revising, I’m not aware of anyone who has “caught” her in a mistake in terms of troop movements or what people wore or what time of day something happened. She even looked at weather reports to make sure she didn’t write “this day it was raining,” when actually it was sunny.

We’re sitting her talking in 2011 when it’s easy to find out such facts, thanks to the Internet, but when she was writing this book, it was a lot harder to find out what was the weather on a particular day in 1865.

ELLEN: Can you imagine?

JOHN: Absolutely. She mentioned looking at old newspapers and having to lay on her stomach--and she was a very small lady--and look through these old newspapers.

ELLEN: And the reference librarians--back in the day when libraries had reference librarians--she was incredibly grateful for them because she could give them some factual question and they were a terrific help. But to the question of whether people caught her in any mistakes, I think the biggest complaint about Gone With The Wind is people saying it’s not a complete view of Reconstruction. It’s not so much that what she presents is inaccurate, but some of the complaints people have with it today is it’s not the full story, especially the African-American experience.

What was her attitude towards the African-American experience and slavery? That is certainly the source of the most bitter complaints about her novel.

ELLEN: It was wonderful talking to Alice Randall, who wrote The Wind Done Gone, about the racial issue. What she said to me was, “Nobody can say for sure what Mitchell’s attitude was.” We have before us what she wrote in her book, and also her letters and things like that. But nobody will be able to say for sure what her feeling was. The best I can tell--my impression of it, and John may have different ones--is she was a product of her time. Was she the most progressive person on racial issues on the earth? No. By no means. But by the same token, she was not the racist that some people make her out to be. I don’t view the book as racist. It was in the Washington Post the other day, somebody sent me a clipping and asking me if I wanted to write a letter to the Post complaining about this. I said, “I can’t take it on.” But really, I think her viewpoint was, and she said this in many letters, that the blacks in her book were actually the most honorable, thoughtful characters in the story. You look at Scarlett--she’s not a heroine by any stretch of the imagination. She’s a mess: she’s manipulative, she’s a liar, she’s deceitful, completely not self-aware. Melanie and Ashley, the two who cling to the ways of the Old South, look what happens to them. Ashley’s completely ineffectual, unable to operate in the new world, Melanie dies. Rhett and Scarlett, the two who accept the reality of the New South, are the ones who go on to survive.

Her ambivalence seems to have extended right up to and beyond publication. When Harold Lathem at Macmillan in New York and her editor friend Lois Cole became enthusiastic about publishing the novel and were trying to coax her into polishing it up, she was reluctant, not really sure the book was worth publishing. She didn’t want to come to New York for a promotional trip, because it was too hot in the summer. And she was indifferent to Lathem’s suggestion that she let Macmillan represent the movie rights for the book. Did you find anything in her correspondence, in her papers, that indicated she was being, for lack of a better term, coy? That deep down she was really excited about all the enthusiasm for her novel, something she had worked on so long and so hard?

ELLEN: I think she was coy in a lot of situations. But as John said, I think she was also insecure. I think she went back and forth between the two, and it was a mixture of those things at play. She never gave up on the book. Even if she wouldn’t play by Macmillan’s rules, she was not going to be ordered around or do things she didn’t want to do. But she never gave up on the book. She obviously always wanted it to have its best success in life. Look how much effort she put into writing letters to fans, thousands upon thousands of letters she wrote to people, signing books, standing in line at the post office, paying the postage. So it was interesting. I think it comes down to her doing things her own way.

Right. She was really tenacious about protecting Gone With The Wind, wasn’t she? She stood up for the book and for her work.

JOHN: Absolutely. I think they really viewed it as their child. As any parent they wanted to protect it. And also don’t take advantage--don’t try to use my work for your own.

The special trailer for Gone With the Wind was shown during the fall of 1939 at the theaters first presenting the film, including Loew's Grand in Atlanta, Carthay Circle Theater in Los Angeles, and Loew's 'flagship' theater in New York. Not one scene from the film is shown; this was intended to whet the public's appetite when it was finally released that December. The movie was given its first ‘sneak preview’ in September 1939 at the Fox Theater in Riverside, CA. The audience went wild..We’ve talked about Harold Lathem and Lois Cole, without whose assistance Margaret’s manuscript might have remained propping up the couch. But there were others you talk about in the book who helped nurture it as it went through the publishing process. Was Norman Berg the most important of the secondary figures who played a big role in seeing the book from manuscript into print? Or can you really single out one person as being so vital to the book being published?

JOHN: Norman Berg played an important part, but I also think Margaret Ball, Mitchell’s long-time secretary, who was with Norman Berg sort of before publication and then of course was with Mitchell, Marsh and [Margaret’s brother] Stephens Mitchell for thirty-some years. Other than Margaret Mitchell, you have to go to her husband, John Marsh, in terms of the importance to the story. But then Lois Cole, Harold Lathem, George Brett, Norman Berg--

ELLEN: I was going to say Alec Blanton.

JOHN: That’s true.

ELLEN: Right after Lois. The marketing director, I’m not sure what the title was, the man who developed the advertising campaign. Just did a phenomenal job. Mind you he had a lot of money to play with because George Brett was willing to invest in it. But it seemed like he had the golden touch.

John, this may be a more of a question for you, since you’ve spent so much time on Gone With The Wind, but Ellen you may have a perspective on it as well. After all this fresh research into her life and the writing of this novel, did you learn anything about her and/or about the book that really surprised you, after all these years of studying?

JOHN: I don’t know that I learned anything that surprised me, but I did gain a greater appreciation for her, especially in the copyright arena. I always knew she had problems with that and she fought it, but once you get down and really start reading it, it is just amazing. She dealt with that for the rest of her life. And every time she thought she had something settled, something new would pop up. And then the fact--this has always fascinated me--she did this before the Internet, she did this during World War II, when you might write a letter overseas and it might take a year to hear back, and she did this from Atlanta. Now Atlanta is this huge international city; in the ‘30s and ‘40s I think Atlanta had 300,000 population and just wasn’t a major anything outside of Georgia. She ran a worldwide publishing empire from her apartment in Atlanta and did an incredible job with it.

Presumably, every other author who has followed her into the international arena benefits from what she did.

JOHN: Absolutely.

ELLEN: You’re preaching to the choir right there. Kind of our rallying cry. I gave a talk to a writer’s group last week and said, “Whether you like Gone With The Wind or not, everybody in this room owes a debt of gratitude to Margaret Mitchell.”

She had a warm and respectful relationship with her foreign publishers, until she learned of a Dutch publisher essentially bootlegging her book and was denied an injunction against the publisher by a Dutch court. That was really the spark that set of this lifelong campaign, wasn’t it?

JOHN: It was such a personal affront to her--how dare you take my property?

ELLEN: And it was never about the money, because overseas publishing rights were worth so little, especially during the war because there was such a scarcity of paper that even if somebody did steal her book to publish it they could only produce a couple thousand copies here and there. It wasn’t about the money--and most money could not be gotten out of Europe. It was really the principle of the thing; it was thievery.

JOHN: And of course it’s ironic that the Dutch publisher, once they settled their differences, they became good friends. For years he sent tulips to be planted on her grave. That says something about both of them.

There are some funny parts to the copyright infringement cases. She would receive copies of these bootlegged books and some were very attractively packaged. She appreciated that, but she couldn’t let them get away with it. Have you seen any of those bootleg copies, John?

JOHN: Yes. I have some. I think they have finally got a contract in Greece, but for decades Greece pirated the book. Whenever they felt they needed a new edition, they popped one out.

When the book was in the editing process, it sounds like, from what you discovered, there wasn’t a great deal of rewriting. It was more organization and putting parts together as opposed to drastic revisions of copy.

ELLEN: That’s exactly right and that’s why it’s so remarkable to have the typescript that the library in Connecticut found. Because for a lot of books, the document would have been revised twenty times before it got to the finished product. But here, because she was so behind schedule, they had no choice but to put it into production. I think twice they had to stop the presses when they realized kinks needed to be worked out in terms of consistencies and, like you said, formatting of the chapters, and also the big issue that drove Mitchell nuts was whether to use quotation marks when referring to Scarlett’s thoughts. Little technical things like that, and some dates had to be clarified, but no substantive editing that we know of.

JOHN: It’s good they didn’t mess with it, because I think that’s part of the magic. It is her book and you wonder, had she gotten an editor who felt, I must change this and I must change that, we may not have the book we have today.

ELLEN: At any point along the way Macmillan could have said, “Let’s call this off and give it another year.”

JOHN: Or, “This is way too long. We need to cut half of it.”

Gone With the Wind trailer marking the Civil War Centennial (1961)In the end, how did she feel about the whole Gone With The Wind saga? In her lifetime it wasn’t what it is now, but there was a substantial fan base for it and there were lots of hard-core Gone With The Wind fans. The whole saga, from book to movie and everything that grew up around it, did she welcome it, did she distance herself from it, regard it suspiciously? What was her take on it?

JOHN: She always appreciated the fans. In the last months of her life she would get letters from younger fans who had just discovered it, and she always graciously replied and thanked them for reading her book. She also always refused to answer what happened to Scarlett and Rhett. She appreciated her fans; she enjoyed the movie--she thought it was a little too Hollywood, but overall she thought they did a very good job with it. And I think as long as she felt she was in control, she controlled it, it didn’t control her. She couldn’t help but be proud of it and was happy with what it had become. I don’t think she could have imagined that it would still be going on; that there would still be copyright issues; that there would have been sequels. I just think that was beyond her imagination.

ELLEN: Beyond anybody’s imagination.

You know there are huge chunks of the book that are not in the movie, of course. If you could add something to the movie that is in the book, what would it be?

JOHN: I think some of the scenes early in the book. For instance, Scarlett sneaks around and reads Ashley’s love letters--not necessarily his love letters, but his letters home. I think that adds something to your understanding of Scarlett. One, she’s bored by them, because they’re sort of formal and he talks about everything he’s going through and the war and she’s going, “Whew! They don’t love each other,” because they’re not the gushy letters she was expecting. I think that’s such a rich little scene I would like to have seen in the movie. But I totally understand. They eliminated two children--

ELLEN: That’s what I wish was in there, because part of what makes Scarlett so god-awful is that she is a terrible mother, just the worst.

JOHN: I think for one character I love the character of Will Benteen. He was so important to Tara after the war that I wish the movie could have included him. Selznick did what he had to do, and I think he gave the perception that he filmed a lot more of it than he did. Three hours and 42 minutes, that’s a long movie, and you have seen a lot, covered a lot of years, there’s been a lot of drama. So you certainly get the feel of the book.

There was a book that came out a couple of years ago that deals with the book and the movie. The author claims that some of the characters in Gone With The Wind were based on real people. Maybe I missed it in reading your book so quickly, but do you have any evidence that she did base, say Belle Watling on some character she knew or knew of, and a couple of other characters as well?

ELLEN: She always said she didn’t. She said give her a little credit for being creative and that she intentionally did not base the characters on any real people, except Prissy, who she said was based on a maid she had known. But for the most part she said it was made up out of whole cloth, and that that was what a writer’s talent was, creating characters. By the same token, every writer draws on experience, certainly, and I think it would be impossible for her not to have incorporated things she had heard about people, and part of the richness of the story is her experience in hearing all the stories and all the research she had done. I’m working on a book now that ties into antebellum Georgia, and I’m reading some original source material of diaries and materials that I’m sure Mitchell must have looked at in researching Gone With The Wind, because so many of the scenarios and snapshots of things have me saying, “Wait a minute! That sounds like it’s out of Gone With The Wind!” I have to say I feel she almost certainly did pull things, but she never did pinpoint specific people.

JOHN: I think the Belle scenario you mentioned is about a woman in Kentucky named Belle Breezing, And of course in her book it’s Belle Watling. It seems so obvious. But I thought, Wouldn’t she at least have changed the name if she were trying to use something and cover it up? We will never know.

As God is my witness…I’ll never be hungry again, nor any of my folk. As God is my witness.Do you think any of the characters, male or female, have Margaret’s qualities?

JOHN: People would suggest that she was very Scarlett-like, and she would get quite indignant over that. I think when her college friend compared her to Scarlett she wrote a scathing paragraph of every horrible thing about Scarlett and how it was the worst thing in the world to compare someone to Scarlett. Others have said she was very Melanie-like in terms of caring for her husband and sick people and that kind of thing. She’s probably a little bit of several characters in her book.

Did she and John Marsh have as good a relationship as it appears? They seem so supportive of each other.

JOHN: To the best of my knowledge, from everything I’ve ever read, they had a wonderful relationship. They were both very supportive of each other. Gone With The Wind people have often talked about what would have happened had he died first. Because she was so dependent on him. Then he had a heart attack in late ’45 and she stepped up to the plate. She not only took care of him but she and Margaret Ball ran the Gone With The Wind business. She was a very strong person. It was the luck of the draw that one of them went before the other. From everything I’ve ever read, I’d say they had a very close relationship.

ELLEN: I think the one thing we struggled a bit with in the book is that neither Mitchell nor Marsh were saints. They were real people. If you had to say what was John’s flaw--I think in previous books he’s been lionized as this great guiding force and she was a little woman who couldn’t have done it without him. My take on it is that that was the image he broadcast, that even Mitchell’s brother and several of her friends said they felt like he curtailed her star a little bit because he didn’t seem to let her enjoy her celebrity and it was really him creating this public relations image of her as being the little housewife who’s been overtaken by all this shocking success. But I don’t criticize him for that; I feel like that was a choice they made together as a best-defense mechanism. I do think they were very interesting characters, and neither was a saint, but they had a remarkably strong relationship that they could survive that level of scrutiny and attention on their lives. Mitchell made it a real point of pride that she did not want her marriage to suffer, as had happened to so many other successful writers.

It’s interesting she complained of so many physical ailments. Seems like she was always having a problem with something relating to her health, but she never used any of that as an excuse to stop doing what she needed to do at any time in her life.

ELLEN: No. You asked about the biggest surprise we had; to me that was the biggest surprise. I had read these other books, and that was really all I knew about Mitchell when we started. If you look at the original draft of the proposal I wrote, I have in there that Mitchell was a hypochondriac and some unfavorable things, but that was not the Mitchell I came to know in her papers. She had these ailments, they were part of her life, but they never held her back any.

Exactly. You cite correspondence in which she writes, “I’ve got so much pain I my back today, but…”

ELLEN: Yes. I came to think of her as so strong and impressive, and I’m happy we’ve told another side of her story. And a lot of it is, again, that glass ceiling sort of thing. There was a one biographer who, any time she stood up for herself, would write, “There she goes again being shrill, look at her just freaking out.” But someone was stealing from her and she was saying, “Stop!”

After all, tomorrow is another day!What about the sequels? Some have sold well, but none have been critically successful. I’ll be the first to admit that I haven’t read the sequels because they don’t interest me. It seems to me that at the end of Gone With the Wind, she has told the story. I don’t need to know anymore. How do the two of you feel about the sequels?

JOHN: I agree with you that yes, it ends where it ends. But I also understand it initially was her brother who finally gave the go-ahead for the first sequel, and it was for legal reasons. The copyright was going to expire, somebody was going to do a sequel without their permission. So the thinking was, Let’s go ahead and authorize one. Not only can we have some control over it, but we might as well make some money too. It took several years before Scarlett came out, which sold millions of copies but was critically torn to pieces. Rhett Butler’s People, which took quite a few more years to come out, was not as commercially successful here, although I think it was very popular overseas, got pretty good reviews. I think people liked the approach he took. I’ve read both of them; I’ve read some unauthorized sequels. Some of them have their strengths, but they’ve never affected how I feel about the original or what I think happened. I read them, okay, I’ve read it, but this is not Gone With The Wind.

So Ellen in this process, you didn’t start out as a Gone With The Wind person. Have you now become a Gone With The Wind person?

ELLEN: I am undoubtedly a Margaret Mitchell cheerleader. I think Gone With The Wind is beautifully written, I think it’s eye opening, I think it’s a wonderful read. It’s entertaining, it’s educational. I think it’s a terrific accomplishment, but my real support is for Margaret Mitchell. I think what she has done for writers, both in terms of her copyright, in terms of showing how to manage dealing with a publisher, she’s a good role model for remaining true to yourself, and how to do deal with the public. She’s a role model in so many ways. People, whether they like Gone With The Wind or not, will find out about Margaret Mitchell and see that there’s plenty to her story that’s worth reading, regardless of what you think about Scarlett and Rhett.

Click here for the New York Times obituary of Margaret Mitchell from August 17, 1949

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024