A Bill Monroe Centennial Moment

‘The one thing he was extremely aware of was that he had fashioned his music.’

The Fortuitous Pairing of Ralph Rinzler and Bill Monroe

(Ed. Note: Nothing against Ronald Reagan--well, maybe a few things--but TheBluegrassSpecial.com feels the far more important centennial to celebrate this year is that of Bill Monroe, the Father of Bluegrass, who would have turned 100 on September 13. Mr. Bill is such a giant of American music that we are honoring his 100th birthday with a Bill Monroe Centennial Moment each month throughout 2011. Sometimes these will take the form of accounts of Monroe's influence on succeeding generations of musicians--as in February’s installment of how young Carl Perkins's discovery of Bill Monroe's music helped him develop the rockabilly rhythm he perfected in the honky tonks around Jackson, TN; sometimes we will look back at a signal moment in the artist's life, as we do this month in recounting how Ralph Rinzler forsook his own musical career to help Monroe rebuild his in the early ‘60s when Monroe was at a low ebb professionally and personally. We are also in the process of commissioning other artists to contribute their thoughts on Monroe's impact, on their work and/or on music in general. We feel it's the most fitting way to honor a great American original.)

A man of great achievement as a musician, folklorist, artist manager, impresario, publisher, and producer, Ralph Rinzler rose to prominence in the 1950s as a member of the Greenbriar Boys and was soon showing up as a supporting musicians on other artists’ album. In 1998 he won a Grammy as a producer of Folkways: A Vision Shared, a benefit album celebrating the Folkways label’s 40th anniversary with the likes of Bruce Springsteen, Emmylou Harris, Taj Mahal, Little Richard and others performing the songs of Lead Belly and Woody Guthrie. HE was a co-founder of the annual Smithsonian Folklife Festival held on the Washington, D.C. Mall every summer, and served the Smithsonian as a curator for American art, music, and folk culture.

In 1962 Rinzler’s path crossed that of Bill Monroe, whose career had been stagnating and, bitter about the music business, proved difficult to get along with. Rinzler, who had been booking Doc Watson for a couple of years (“the task was to recognize the value of an unknown musician, and introduce him to a national audience,” Rinzler told his biographer, Richard Gagné), decided in 1963 to move to Nashville and concentrate on rebuilding Monroe’s performing and recording careers. At that time, Rinzler recalled Monroe “felt that everyone had stolen bluegrass from him. Flatt and Scruggs were making thousands a night, and he was making hundreds.”

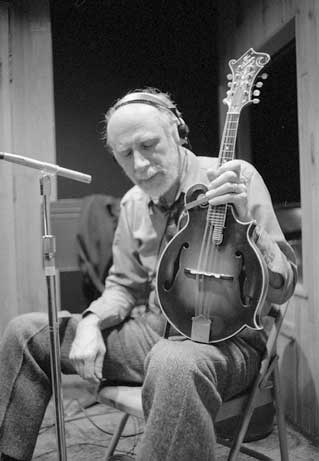

Ralph Rinzler (1934-1994), founding Director of the

Smithsonian Folklife Festival at a recording session in 1988, by Dane Penland, Photographic print, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 98-015, Box 2, Folder: August 1994, Negative number: 88-1476-20.As Rinzler recounted to Richard Gagné: Monroe is this giant, whose songs had been recorded by Elvis Presley, and who had been on the Grand Ole Opry 20-some years, he was like a nova, I mean people were astonished with him. But he couldn't make a living because Flatt and Scruggs had sewed up the whole business with the Ballad of Jed Clampett, Bonnie and Clyde, and the Beverly Hillbilly stuff... Trying to get Monroe to talk to you, he just didn't want to be interviewed. But I was determined. It took me three months to get an interview from him. And publish it in Sing Out!

And when you finally sat down to talk to him, even as reluctant as he was about the idea of being interviewed, he answered every question very diligently. And at the end of the interview I said, "Is there anything you've said that you don't want to see in print?” And he just looked up and he said, "Well, it's all true."

And once he saw the stuff that I'd written, which unequivocally credited him with having launched everybody else, the next morning after he read the stuff he was a totally different person, and he never changed after that. And it made it possible to begin to understand somebody who was really totally inaccessible before...

And then, all of a sudden, after accepting the role of patriarch, he would talk about his Uncle Pen [Pendleton Vanderver], and about retuning the mandolin into fiddle tunings that his uncle used. And he would talk about a concept that he had about “old tones,” which meant modal, mostly, for him. So working with those kinds of artists, who were really among the greatest musicians of their time, was an exercise in getting the best out there. Because Monroe couldn't make three or four hundred dollars a night at the beginning of this experiment, but he was soon just cleaning up. But it took getting the folk song audience to understand that he was as folk as he was Nashville. And to give them the actual facts of who he learned from and how and what his philosophy was. And once he realized that people were interested in his ideas, he was very voluble on the stage and very gracious.

Bill Monroe and The Bluegrass Boys, ‘I’m Working On a Building’In his 1971 book Bossmen: Bill Monroe & Muddy Waters, author James Rooney quotes Rinzler discussing how he developed his relationship with the father of bluegrass:

“The reason Bill was in the dumps in the fifties was the takeover of rock and roll at the time of Elvis Presley, and it threatened all of country music for a while. Another factor was that Flatt and Scruggs had cornered the marked on what was left.

“Bill was left behind in the way that he was because he stuck hard by what he believed in, and he also had no business organization behind him. Mrs. Scruggs managed their business very shrewdly and the impression was created that bluegrass began and ended with Flatt and Scruggs.

“By sixty-one Flatt and Scruggs had come north. Pete Welding wrote an article in Sing Out! about how Scruggs had made obsolete everything that had come before it and claimed him as the master of bluegrass music. I was furious and asked to do a story on Monroe.

“None of us had ever talked to him. He was very aloof. I asked him if would give an interview and his reply was, “If you want to know anything about bluegrass, ask Louise Scruggs.” And he turned and walked away. Finally, however, his companion and bass player for many years, Bessie Lee Mauldin, and Carter Stanley persuaded him.

Bill Monroe and Doc Watson, ‘Watson’s Blues,’ from the Smithsonian Folkways album, Off The Record, Vol. 2: Live Duet Recordings, 1963-1980“The one thing he was extremely aware of was that he had fashioned his music. His music didn’t happen and it wasn’t intuitive. He consciously did it. The way a painter takes his brush and dips his brush into different colors on that palette, he can tell you exactly where he gets sound in his music.

“He has a whole philosophy of why it is important to get something out of a tune that’s in it. You get the essence out of a tune by playing the melody. On records he’ll play note for note the essence of that tune, but when he gets to the last line he’ll play something that’s pretty far out and he’ll save that, and you’ll know it’s coming and he does that so intentionally, and he knows exactly what you’re waiting for. All the subtleties in his music are so intentional. He remembers so much from his childhood that he has put into his music. And it’s not only a memory. It’s sensitivity to people and values, and to beauty.”

“Ralph Rinzler worked with Monroe from 1962 to 1966,” Richard Gagné wrote in summary. “During those years, Monroe released ten albums. Another 27 albums followed between 1967 and 1991. In the case of Bill Monroe, Ralph Rinzler revived the career of the founder of an entire musical genre. He helped bring bluegrass, as well as old-time music, into the fold of the folk music revival.”

***

Art Inspired by Bill Monroe On Exhibit and For Sale at International Bluegrass Museum

At the International Bluegrasss Museum in Owensboro, KY, now through September 15, is a display of art inspired by Bill Monroe’s music, sponsored by an Arts Build Communities grant through the Kentucky Arts Council

This Exhibit is the result of an invitation to visual artists to share their interpretation of a Bill Monroe song. Bill Monroe often painted images with his music and in this Exhibit artists have depicted their versions of these same images visually. Thirty-five artists responded to the invitation, with over sixty entries. The entries encompass many styles, from fine art to folk art. This is representative of the wide variety of people to whom Bill Monroe's music appeals.

Gingham Rose by Rachael Sinclair, Louisville, Kentucky. Inspired by ‘My Rose of Old Kentucky.’ Acrylic on canvas. 19" x 23"/$400.Most of the works of art submitted were inspired by the lyrics of a Bill Monroe song, while some were inspired by instrumentals; some were inspired by songs Monroe wrote, others by songs from other sources that Monroe covered and stamped as uniquely his.

Springtime in the Bluegrass by Frederica Diane Huff, Philpot, Kentucky. Inspired by ‘My Sweet Blue-Eyed Darling.’ Watercolor on paper. 18" x 24"/$500The pieces of art selected for the Exhibit are listed in this catalog in alphabetical order by artist. All the art on display in the Exhibit is available for purchase at the prices listed. Sixty percent of the proceeds will go to the artist and forty percent will go to the Museum. If you are interested in purchasing any of the artwork please contact Forrest Roberts at forrest@bluegrassmuseum.org.

For more information on the Bill Monroe Centennial celebration festivities at the International Bluegrass Museum, visit the Museum website, and please make a donation to support its worthy effort to document the history and evolution of bluegrass and to promote the music to new generations.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024