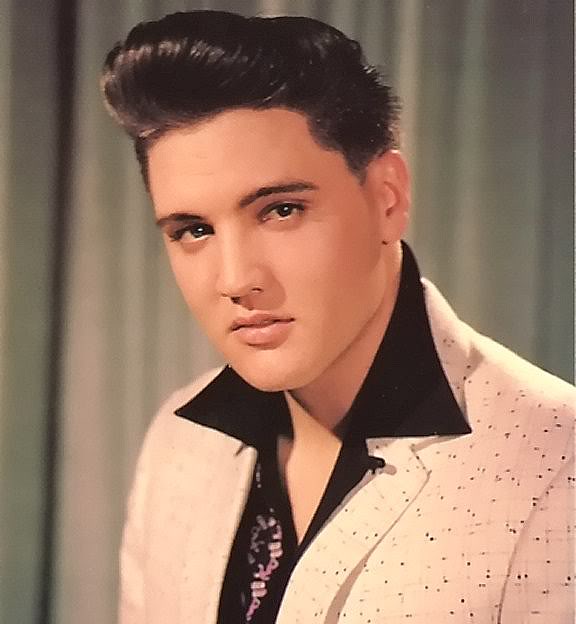

Elvis Presley in a 1960 publicity photo. Did he still have it? Oh, yeah.The Comeback Kid

When Elvis returned from his Army service, some were wondering if he still had it. His first two studio albums proved a big point: He still had it. Oh, did he have it.

By David McGee

Elvis Is Back! (Legacy Edition)

Elvis Presley

RCA/LegacyWhen Elvis Presley returned to civilian life on March 3, 1960, following two years in service to his country as a member of the U.S. Army, a hectic schedule of professional commitments awaited him, along with considerable apprehension over whether his fabled 50,000,000 fans were still united in such numbers in their love of him and his music. Did he still have it, and in turn, them?

In April 1959, less than a year before his discharge, Elvis had recorded himself at home in Goethestrasse, Bad Nauheim, Germany. Much as the songs he had run through with his buddies Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis and Carl Perkins at the Sun studio on December 4, 1956 (the famed Million Dollar Quartet) reflected all those artists’ solid grounding in blues, country and gospel, Elvis’s home sessions in 1959 show that he hadn’t drifted from his core influences, only updated them a bit: the songs include the country ballads of Hank Williams (“I Can’t Help It [If I’m Still In Love With You]”) and the western-flavored country poetry of Bob Nolan (“Cool Water”); deep gospel (Thomas A. Dorsey’s “Take My Hand, Precious Lord,” recorded in ’57 for his Peace In the Valley EP and included on the B side of his first Christmas album; “I Asked the Lord,” “Stand By Me” and “His Hand In Mine,” which would be the title track of his first gospel album); quintessential early R&B (Jesse Belvin’s “Earth Angel,” Ivory Joe Hunter’s “I Will Be True,” Little Richard’s “Send Me Some Lovin’”); and sentimental ballads that touched him deeply (“Danny Boy,” “I’ll Take You Home Again, Kathleen,” “There’s No Tomorrow”). Apart from a run-through of “Loving You” and tacking “Hound Dog” onto the Doris Day hit, “Que Sera Sera,” he did not reprise any of his ‘50s landmarks. As far as we know the only song on the home recordings he was considering for a commercial release when he was back in the world was “Soldier Boy,” a soft, longing, group harmony-style love ballad that had been a hit a 1955 hit for the Four Fellows.

Those 1959 home recordings prove to be the template for the more mature Elvis, who was 25 years old when he came out of the service and a bit beyond singing “Teddy Bear” or “Wear My Ring” except for fun. Those who were with him in those days have reported his intense interest in finding songs with well-crafted lyrics reflecting more adult concerns. When he entered RCA’s Studio B in Nashville on March 20, 1960, for his first post-Army sessions, he leaned mostly on known entities for material: Otis Blackwell, who had written “Don’t Be Cruel” and “All Shook Up,” and was an Elvis favorite for his straight-ahead lyrics, had a winner in an uptempo entreaty to a recalcitrant lover, “Make Me Know It,” and Elvis, with the Jordanaires providing exuberant, bass-heavy background vocals, romped through it with infectious energy, Elvis’s voice light and bright. It was the first song of the session, it took 19 takes to get right, and it was exactly what was needed at a critical moment in Elvis’s history. Assembled at the studio were all the important figures in Elvis’s career at the time: his manager, Col. Tom Parker; Parker’s partner, Tom Diskin; from RCA, Bill Bullock and Steve Sholes (the latter of whom had signed Elvis to the label). A new engineer, Bill Porter, was in place, as well as new three-track gear that would improve the quality of the recordings considerably (for one, by allowing for a separate track for Elvis’s vocals). In the band, in addition to guitarist Scotty Moore and drummer D.J. Fontana, who had been with Elvis from the start, were the same players who had meshed with Elvis so well in his last pre-Army sessions in 1958: guitarist Hank Garland (who played a new six-string electric bass); bassist Bob Moore; drummer Buddy Harman; Floyd Cramer on piano; Boots Randolph on sax; and the Jordanaires.

Elvis, ‘Make Me Know It,’ written by Otis Blackwell. First song cut at the Elvis Is Back! sessions, March 20, 1960All concerns anyone harbored about Elvis losing something while stationed in Germany were allayed by the performance of “Make Me Know It.” As Elvis archivist/historian Ernst Jorgensen notes in his essential chronicle of Elvis’s recording history, Elvis Presley: A Life In Music, a new mood took hold when “Make Me Know It” was completed. As Bill Porter told Jorgensen: “I felt a lot of the tension in the room. I really did. Right at my elbow almost was Colonel Parker, this VP from RCA [Bill Bullock], Steve Sholes—I mean, I could reach out and touch them. When Elvis did the first tune, they didn’t say anything to me, but once he got the first tune down, they all started talking about other things. So it was, apparently, the anticipation of him singing again in the studio.” And, Jorgensen adds, “‘Make Me Know It’ couldn’t have done a better job putting them all at ease.”

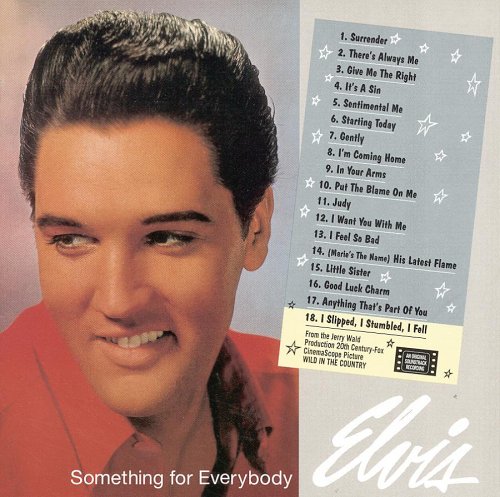

So began one of the most satisfying albums of Elvis’s career, the logically titled Elvis Is Back. Given the circumstances of its recording, being squeezed in between a number of other projects, it’s amazing it came out as well as it did, but that it did is a tribute certainly to the outstanding musicians—and their stamina, as several songs required a grueling number of takes before Elvis was satisfied—who were studio-seasoned, able to turn on a dime and respond in kind to Elvis’s readings; and, to say the least, it’s a tribute to Elvis being focused, enthusiastic and committed to the task at hand. Since we don’t really know to what degree Elvis understood the gravity of the situation, we can only assume by the strength of his performances that he intended to make a statement with Elvis Is Back, something more than what the title says: no mere return, Elvis Is Back asserts unequivocally a new direction for the artist. It would be almost a year to the day before he was able to record again with the same single-mindedness as he evinced in March 1960 (and on a second session, on April 3), when he returned to Studio B on March 12, 1961, for sessions that would be released as Something For Everybody. One of the best and most underrated of all Presley albums, Something For Everybody is replete with simply breathtaking vocals on which the King exercises flawless command of the textures of his voice—the soft, caressing tone; the bravura, operatic ascensions; the bluesy drawls and swagger—and brings an advanced sense of drama to the affair as well, demonstrating what one of his favorite songwriters, Doc Pomus, once said of him: “He sings the song—plus.”

In between these albums would be an appearance on a Frank Sinatra TV special; soundtrack sessions for G.I. Blues, Flaming Star and Wild In the Country and sessions for Elvis’s first gospel album, His Hand In Mine. Without discounting the importance of gospel to Elvis’s art—or the fine, nuanced work he did on the soundtracks, especially Flaming Star and Wild In the Country--Elvis is Back and Something For Everybody are the telling clues to his post-Army artistic aspirations.

This is easy to discern now that RCA/Legacy, continuing its Elvis 75th birthday tribute, has packaged the two albums together with non-album hit singles recorded around the same time as the album tracks—36 cuts in all, not a half-baked one in the bunch. In one fell swoop, this release lays to rest John Lennon’s claim that “Elvis died after he went into the Army,” a bit of uninformed bloviating bought on faith lock, stock and barrel by a couple of generations of music critics unwilling to examine all evidence to the contrary, meaning the music Elvis recorded for these long players.

Elvis, ‘The Girl of My Best Friend,’ from Elvis Is Back!Elvis Is Back sounds like Elvis looking back and looking ahead all at once. The aforementioned “Soldier Boy” has the appropriate ‘50s group harmony feel, with Elvis’s emotive tenor out front and the Jordanaires providing tight, repetitive doo-wop backgrounds, Scotty Moore injecting taut, upper strings riffs along the way, and Floyd Cramer sprinkling bluesy, right-hand piano runs throughout. In direct emotional contrast to “Soldier Boy” is one of the classic performances of “Fever,” modeled after Peggy Lee’s smoldering version, with Elvis’s restrained, sultry approach lent added heat by the spare atmosphere around it—finger snapping, Bob Moore’s laid-back acoustic bass, and Buddy Harman’s emphatic congas. What a lovely way to burn, indeed. “Fever” is the second track on Elvis Is Back, and it, more than any other, solely on the strength of Elvis’s cool sensuality, announces a more sophisticated artist than we had encountered in the ‘50s. Then, as if acknowledging ‘50s teen misery ballads, Elvis took 10 takes to deliver a spot-on reading of controlled anguish in “The Girl of My Best Friend” (covered in 1961 in a pretty cool version by Ral Donner, an Elvis soundalike who exaggerated his delivery where the King pulled back, but sold it effectively enough to register a #19 hit single). For the rockers in the audience, there’s “Such a Night,” a humorous, horn-enriched take (Elvis almost sounds like he’s parodying himself at points) on a lover who is gone but most certainly not forgotten, or at least aspects of her are not forgotten, which works itself up to a climax explosive enough that when the band is roaring you hear Elvis exclaim “Yeah!” as he comes off the last phrase; and from Leiber and Stoller, architects of so many of Elvis’s enduring ‘50s monuments, came a raucous, blaring, blues-drenched rocker, “Dirty, Dirty Feeling” that sounds for good reason like it might have come from L&S’s King Creole soundtrack music—they in fact wrote the tune for the movie, but refused to submit it after getting into a dispute with the Colonel.

Elvis’s Peggy Lee-inspired ‘Fever,’ the second cut on Elvis Is Back! announces a more sophisticated artist than we had encountered in the ‘50s.As impressive as “Fever” is, Elvis’s swagger through two blues numbers is arguably even more potent: his grinding, intense delivery of “It Feels So Right,” by Fred Wise and Ben Wiseman, summons memories of the heat he brought to his steamy 1957 cover of Smiley Lewis’s (by way of the pen of Dave Bartholomew) “One Night” (Wise purposely followed the “One Night” model when writing “It Feels So Right”); even better is Lowell Fulsom’s “Reconsider Baby,” unquestionably one of the most consequential blues performances Elvis ever laid down. Floyd Cramer, he of the famous “slip-note” style that was becoming ubiquitous in country music at that time, thanks to Cramer playing on so many hit sessions—is running some frantic blues piano on the track while sax man Boots Randolph, who would become famous for his sputtering “Yakety-Sax” in 1963, is doing a Big Jay McNeely on us (or maybe an Illinois Jacquet circa 1946’s “Blue Mood”) with some lowdown blowing that doesn’t preclude a few honking, sputtering flights he would develop to greater effect in a couple of years. All this would be for naught if Elvis didn’t deliver the goods vocally, but he does, many times over, with a controlled reading dripping with disdain and contempt for the woman who’s bailing on him, even as the lyrics sound a contrite note, although Elvis makes sure anyone who’s listening knows he’s well fed up. It’s a masterful, multi-textured performance, a great track, and you feel the synergy between the singer and the band as the tune moves forward (at one point you can hear Elvis encourage the musicians’ commentary with “yeah, yeah”). Even at 25 Elvis sounds too young to be so wise in the ways of the world, but there’s no faking the feeling that he hammers home with, it must be admitted, a certain amount of satisfaction with his unceremonious kissoff.

The bonus hit singles tracks on the Elvis Is Back disc are indisputable classics: the exotic, operatic “It’s Now or Never,” with its big, booming vocal signoff following a reading full of tenderness and romantic longing; the melodramatic treatment of the old standard “Are You Lonesome Tonight,” with its memorable midsong recitation, modeled after the performance of one of Elvis’s favorite singers, the Ink Spots’ Bill Kenny; the onset of the Doc Pomus-Mort Shuman Elvis legacy with two entries--the swinging “A Mess Of Blues,” full of mordant humor that Elvis locked into in crafting a mock-braggadocio treatment, and a fevered come-on, “Surrender,” in an arrangement blending Italian (by way of Hank Garland emulating mandolin trills on guitar) and Latin influences (clacking castanets), adapted by the songwriting team from the Neapolitan ballad “Torna a Sorriento.” “Surrender” was especially crucial to Elvis himself, as Elvis’s biographer Peter Guralnick noted in Careless Love: The Unmaking of Elvis Presley: “[“Surrender”] offered him the opportunity to prove to his critics that the ambitious new direction he had first embraced with “It’s Now or Never” (which had gone to number one the previous summer, far outstripping “Stuck On You” in sales) and “Are You Lonesome Tonight?” (due to be released as the new single within the next couple of weeks) was no fluke.”

Elvis, 'Surrender': ‘the song offered him the opportunity to prove to his critics that the ambitious new direction he had first embraced with ‘It’s Now or Never’ and ‘Are You Lonesome Tonight?’ was no fluke.’In the end, Elvis Is Back, an “eclectic, and truly adult, album,” as Guralnick observed, sold less than half a million copies; in fact, the G.I. Blues soundtrack sold better. Thus one reason the album has been something of a best-kept secret among Elvis aficionados. But as Guralnick also notes, something important emerged from the March 20 sessions that had nothing to do with sales, but everything to do with the future.

“RCA wasted no time in capitalizing on the session’s success,” Guralnick writes in Careless Love. “Within seventy-two hours they had pressed up 1.4 million advance orders for the new single (“Stuck On You” and “Fame and Fortune”) and shipped them out in preprinted sleeves that announced only ‘Elvis’ 1st New Recording For His 50,000,000 Fans All Over The World’ in the absence of definitive titles at the time they had gone to press. They finalized arrangements, too, for a second session to follow the Sinatra taping, which would ensure completion of the album, already entitled Elvis Is Back and scheduled for mid-April release, before Elvis’ departure for Hollywood. After all the frustrations of dealing with the Colonel, and all the worries that he had caused them, Bill Bullock finally felt as if they had some breathing space. Judging by his attitude and performance, there seemed little question: Elvis really was back.”

A tour de force of sensitive crooning and balladeeringSomething For Everybody was another rush job, done at RCA’s behest to fulfill a contractual commitment at a time when Elvis was in the midst of rehearsing with his band to cut the soundtrack for Blue Hawaii in Hollywood. Despite the time constraints it was up against, Something For Everybody (a thoughtless title, as if there weren’t time or energy enough to come up with a more compelling sentiment to complement and elevate the long-player’s unusual sensibility) is a tour de force of sensitive crooning and balladeering. The hit single tracks included on this disc spit fire for the most part—two incendiary Pomus-Shuman classics, “(Marie’s The Name Of) His Latest Flame” and the merciless “Little Sister”); a bouncy, feel-good Aaron Schroeder gem in “Good Luck Charm”; an anxious take on Chuck Willis’s 1954 hit, “I Feel So Bad”—but there is also a stunning heartbreaker of a ballad, “Anything That’s Part of You,” from Don Robertson, new to the Presley camp but already a winner in Elvis’s estimation. Elvis could hardly have given a more anguished testimony of emotional devastation as he did on the Robertson ballad, emphasizing the utter loss the lyrics describe with a gospel-tinged approach similar to what he employed in exploring some of the more reverent hymns he had recorded.

Elvis, ‘There’s Always Me,’ by Don Robertson, the lead track on Something For Everybody sets the mellow tone for the first half of the album. Robertson became one of Elvis’s favorite writers. He recorded two of his ballads for this album.For the album tracks proper, though, the mood was mellow, the style bluesy, the spirit tender. Robertson’s “There’s Always Me” kicked it off with a late-night saloon feel before winding up with a roaring coda, and the next five songs—the churning Fred Wise-Norman Blagman R&B ballad “Give Me The Right”; Fred Rose’s aching heart ballad, “It’s a Sin,” a song Elvis had seen Eddie Arnold perform in 1954 on the night he had told Gordon Stoker that he wanted Stoker’s Jordanaires to back him someday; the languid love ballad, “Sentimental Me,” originally an Ames Brothers hit in 1949, done in an easygoing arrangement with the Jordanaires shadowing Elvis’s vocal and Elvis singing the lyrics’ sweet-natured sentiments in his high, pillowy upper register; another gem of a Don Robertson tearjerking ballad, “Starting Today,” notable for Floyd Cramer’s evocative country piano; a folk-flavored chronicle of love flowering, “Gently,” with the delicate harmonizing of Elvis and the Jordanaires framed by Hank Garland’s exquisite, atmospheric fingerpicked guitar.

Not until halfway through the album does the pace pick up when Elvis and band take a run around Charlie Rich’s bopping “I’m Coming Home,” with Cramer working out on the 88s as if Jerry Lee Lewis had taken possession of his soul (he even slips in a Killer glissando) and Scotty Moore tearing off a howling solo reminiscent of the Sun years. Aaron Schroeder contributed a bouncy, playful love song, “In Your Arms,” an uptempo workout featuring Millie Kirkham adding a pleasing female voice to the Jordanaires’ harmonies and Boots Randolph erupting with a blaring sax solo; the energy Randolph injected into the song was similar to what Cramer contributed with his happy organ rollicking shaggily through the stomping “Put the Blame On Me,” as Elvis sang with assured abandon and marvelous theatrical feel for the narrative arc.

Elvis, ‘Judy’: ‘It’s doubtful that one can find any real match for the effortless grace and swing, the sheer unforced mastery, of Elvis’s vocal on ‘Judy’’Elvis didn’t record many songs with girl’s names in them, but “Judy” rivals “(Marie’s the Name of) His Latest Flame” as the best of this elite category in his catalogue. Ernst Jorgenson describes it best in Elvis Presley: A Life In Music: “It’s doubtful that one can find any real match for the effortless grace and swing, the sheer unforced mastery, of Elvis’s vocal on ‘Judy.’ Playing acoustic guitar for himself (gradually and deliberately buried in the mix as the takes progressed), Elvis told the band, ‘Twice in D,’ then led them through a cover of Teddy Redell’s 1960 Atco recording. Floyd Cramer scattered his right-hand triplets like gold dust over the track, which epitomized Elvis and his Nashville band’s particular brand of timeless pop.”

The quieter songs, though, afforded Elvis an opportunity to demonstrate his growing facility as an introspective, sensitive balladeer. Had he lived longer, maybe he would have gravitated toward the lyrically and musically sophisticated fare of the Great American Songbook, or the rootsy equivalent of that, and produced his version of Sinatra’s For the Lonely, for instance. He had it in him, as the ballads on Something For Everybody prove, and on evidence of the orphaned recordings (non-album singles and non-single album cuts) that were assembled on The Lost Album, now out of print, and on wonderful performances buried on soundtrack albums critics are so quick to disparage: “Summer Kisses, Winter Tears” from Flaming Star; “Lonely Man,” the beautiful “In My Way,” “Forget Me Never” and “Wild In the Country,” all from Wild In the Country, the unlikeliest torch soundtrack ever.

Elvis, ‘(Marie’s The Name of) His Latest Flame,’ by Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman, one of the hit singles recorded during the Something For Everybody sessions and included on the Elvis Is Back! Legacy Edition.Finally, this wonderful double-disc reissue reminds us once again of the depth of Elvis’s musicality. A taskmaster in the studio who wouldn’t stop until he felt he had nailed a vocal, he inspired in his band members a similar high standard of excellence in their playing. Rampant on these two discs are moments of incredible artist-band interaction, moments when you can’t imagine a song being better realized than it is here. When this happens, something spiritual emerges from the music that connects Elvis to his audience in ways only music can do and cannot be easily explained beyond helping us understand ourselves. It’s not Miles Davis on Kind of Blue, forging ahead into uncharted territory and drawing new maps of the world. It’s more elemental and elementary than that, but every bit as deep, because it comes back to the heart, always back to the heart. Would that we could ask Elvis about this, because the search for the heart—his, ours--is so central to his odyssey in life and on record, something of his Rosebud.

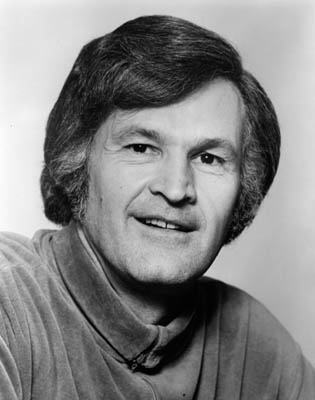

Elvis, ‘Anything That’s Part of You,’ by Don Robertson, recorded for Elvis For Everybody: Elvis could hardly have given a more anguished testimony of emotional devastation.After Elvis had recorded a couple of his wonderful ballads, Don Robertson received an invite to join Presley in the studio during the Blue Hawaii soundtrack session. In Careless Love, Peter Guralnick got the story straight from Robertson about the songwriter’s unforgettable experience with Presley. When all the lurid tales about Elvis’s private life become tired, if they aren’t already, this is an important part of what will be remembered of the man, as Robertson related:

Don Robertson“I sat in the control room, and he came in during a break and introduced himself (he was standing there in his little captain’s hat), and we talked some, and he told me how he got started in the music business. He was very charming, very humble, sweet, an altogether appealing person. That night, before I left he told me that some of the musicians and the Jordanaires were going to be coming up to his house after the session, and would I like to come? While I was there, he played me his version of ‘There’s Always Me’—it was the first time I heard it, and we listened on headphones because he didn’t want the rest of the people in the room necessarily to hear it. I remember, he got almost operatic at the end, just like he did on ‘It’s Now or Never,’ and he said, ‘Listen to this ending.’ He was very proud of it. And he talked with me about the lyrics, he was very interested in the lyrics. It was almost like he wanted me to know that he understood everything that was going on, everything that was intended in the lyric. I don’t think I was overawed by him, but I was totally disarmed. He had this talent for making people feel comfortable, for letting you know that he really liked and respected you. And, you know, he told everyone that night that I was the one that had started Floyd Cramer’s ‘slip-note’ style [the grace-note approach to country and western piano that was sweeping Nashville at that time]. I think he was kind of proud of me on that account.”

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024