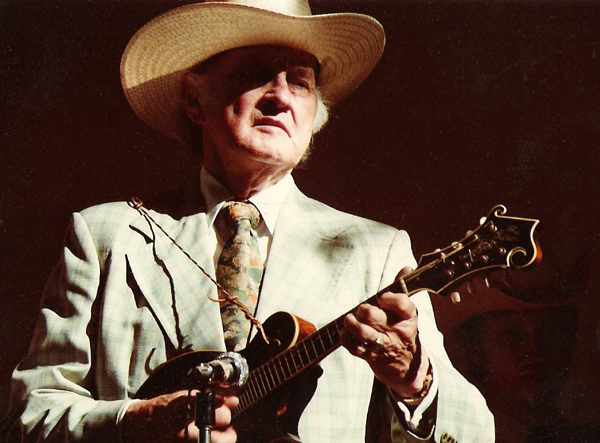

A Bill Monroe Centennial Moment

Father and Sons

Seeing former Bluegrass Boys thriving in groups outside of bluegrass gave Bill Monroe a new pride in the legacy he had passed along to them

(Ed. Note: Had he lived, Bill Monroe, the Father of Bluegrass, would be 100 years old on September 13. Mr. Bill is such a giant of American music that TheBluegrassSpecial.com is honoring his centennial year with a Bill Monroe Centennial Moment each month throughout 2011. Sometimes these will take the form of accounts of Monroe's influence on succeeding generations of musicians--as in February’s installment of how young Carl Perkins's discovery of Bill Monroe's music helped him develop the rockabilly rhythm he perfected in the honky tonks around Jackson, TN; other installments will focus on a turning point or key juncture in Monroe’s life, as is the case this month when we see how Monroe reacted to Bluegrass Boys alumni forming or joining new bands outside the bluegrass world and realized the value of the legacy he had passed on to them.)

As the ‘60s wore on, Bill took notice of something different happening when the younger members of his Bluegrass Boys left the fold to go out on their own: they weren’t forming or joining other bluegrass bands. Instead, they were joining experiments in fusion styles--jazz-rock, country-rock--or throwing in with folk groups that favored a jazz approach to improvisational instrumental music and were reinventing old-time music with a modern flair.

Bill Keith joined the Jim Kweskin Jug Band, then played pedal steel guitar with the Canadian folk duo Ian & Sylvia (Ian Tyson had written “Four Strong Winds” and “Someday Soon”), and then moved over to play with former Kweskin Jug Band members Geoff and Maria Muldaur, who were doing their own avant-folk thing. Peter Rowan did form his own group, Earth Opera, but when it sputtered he joined Richard Greene in the jazz-rock outfit Sea Train. Byron Berline moved into the Dillard and Clark Expedition lineup and did session work with the Rolling Stones, among others.

Seatrain, featuring former Bluegrass Boys Richard Greene (fiddle) and Peter Rowan (guitar, vocal), offered a different take on ‘Orange Blossom Special’ on the group’s second self-titled album, which was also George Martin’s first post-Beatles production.To Monroe these career paths proved his theory that bluegrass was a good training ground for musicians, period, whether they wound up in bluegrass or gravitated elsewhere. He began to regard his alums as extensions of himself, wherever they were. He remained a part of them.

Monroe: “Now recently a lot of fine young musicians have been with me: Bill Keith, Pete Rowan, Richard Greene, Steve Arkin, Gene Lowinger, Byron Berline. They got to loving this music, you know. It’s good music to learn on. I think when you can play bluegrass, you can really play any kind of music, if you really wanted to. You could go right from bluegrass into jazz or anything. You know, it got into Pete’s blood to be a bluegrass guitar man and singer. And of course Bill, I guess, I don’t k now where he started learning, but it was a good push to banjo playing. And Richard made into a good fiddler. I guess he loves the fiddle as well as anybody in the world. But you know Richard got that jazz in his mind, that he was going to be a great bandleader of nothing but jazz, and that proves how hard it gets after you get out on your own. It takes backing to get that stuff going. Arkin could play the best backup banjo I have ever heard. He could beat Bill all over playing a backup. Now there ain’t no way around it. He could do it. He could put stuff in it and make it sell. Bill might put the same stuff in it but it wouldn’t do what that boy [Steve Arkin] could do with it. But he couldn’t carry a melody like Bill could.

Peter Rowan left Bill Monroe’s Bluegrass Boys to form Earth Opera, a folk-psychedelic group (signed to Elektra) that also featured David Grisman. This song, ‘Dreamless,’ is from the band’s self-titled first album, issued in 1968. For the second Earth Opera album, The Great American Eagle Tragedy (1969), Rowan enlisted the steel guitar services of Bill Keith, another former Bluegrass Boy. Earth Opera disbanded after its second album barely made the charts.“Now he’s got a number of mine and Pete Rowan’s got a number of mine. The one that Pete’s got is a song that I made when he was in Montreal the first trip and Arkin’s got a good banjo number. But it had to come from him before we could get it straightened out. And Pete’s got this other number that had to come out of him to get it. That’s a fine number, man. It’s got a lot of music in it. Deeper than bluegrass needs to play. It would take a good hand to play it. But that’s two numbers that I need to get ahold of, because they belong to me.”

This was also a time in his life when Monroe gained a new appreciation for the music the former Bluegrass Boys were carrying to new audiences and a certain pride in handing off the old tunes to another generation of musicians. At the same time, he persisted in his strong feelings about how the music should be played--feelings he made sure his band members absorbed.

“I have followed instrumental numbers for so long that I know how they should go,” he said. “I know if it is getting out of line. I know the minute if you have the melody and go on someone else’s tune. That’s studying it and listening to tones and knowing what tone should follow another. Now I know that tunes like ‘Roanoke’ or ‘Turkey In the Straw’ don’t need changing. They’ve got everything in them they need. Now if you could come up and play the same melody in another position, why I’m 100 percent for it. So if you’ve heard a fiddler all your life--maybe you’ve danced after him--he still hasn’t put enough time on it to really learn how it should be played--maybe he was playing for a square dance and making money and that’s all he was interested in. He wasn’t interested to learn the number and play it the right way. And that’s when a man should learn to follow the melody is when he’s a young boy. He should take time to learn which way it should go and go that way. If it’s ‘Fire on the Mountain’ or any number like that that’s got the notes the way the man wrote it and if it sounds good to you and you think he did a good job with it, you should put every note in it that he did if you can. You shouldn’t leave anything out. Many banjo players will cut through and hide behind their licks and not take time to learn which way the melody goes and what notes should follow the other.

‘You can’t beat that kind of music with a stick, I don’t care what you say’: Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys(Carlos Brock: guitar; Bobby Hicks, Charlie Cline: fiddles; Jackie Phelps: banjo; Ernie Newton: bass) tear it up on ‘Roanoke,’ as seen on The Country Show with Stars of the Grand Ole Opry, 1955. The host is Little Jimmy Dickens.“If you’ve played music all your life, when you get on up in years you see the things that you’ve done for people and you want to do more for them as you get older. I guess there’s many times when I could have been helped too in the way of a mandolin but if you’re running something--if you’re the boss of it, why, there’s not everybody coming along and saying, ‘Well, you play it this way. You’re not playing it right.’ They think, ‘If I said that, he might fire me.’ I guess everybody could be helped at times.”

(Bill Monroe quotes from James Rooney’s Bossmen: Bill Monroe & Muddy Waters, Hayden Books, 1971)

***

Art Inspired by Bill Monroe On Exhibit and For Sale at International Bluegrass Museum

At the International Bluegrasss Museum in Owensboro, KY, now through September 15, is a display of art inspired by Bill Monroe’s music, sponsored by an Arts Build Communities grant through the Kentucky Arts Council

This Exhibit is the result of an invitation to visual artists to share their interpretation of a Bill Monroe song. Bill Monroe often painted images with his music and in this Exhibit artists have depicted their versions of these same images visually. Thirty-five artists responded to the invitation, with over sixty entries. The entries encompass many styles, from fine art to folk art. This is representative of the wide variety of people to whom Bill Monroe's music appeals.

The Tokyo Moonlight Waltz, by Lex Eni, Henderson, KY. Inspired by ‘Come Hither Go Yonder.’ Oil on canvas. 16” x 20”. $300Most of the works of art submitted were inspired by the lyrics of a Bill Monroe song, while some were inspired by instrumentals; some were inspired by songs Monroe wrote, others by songs from other sources that Monroe covered and stamped as uniquely his.

Mule Skinner by Rebecca Jo Goodman, Sturgis, KY. Inspired by ‘Mule Skinner Blues.’ Acrylic on paper. 24” x 30”. $475.The pieces of art selected for the Exhibit are listed in this catalog in alphabetical order by artist. All the art on display in the Exhibit is available for purchase at the prices listed. Sixty percent of the proceeds will go to the artist and forty percent will go to the Museum. If you are interested in purchasing any of the artwork please contact Forrest Roberts at forrest@bluegrassmuseum.org.

For more information on the Bill Monroe Centennial celebration festivities at the International Bluegrass Museum, visit the Museum website, and please make a donation to support its worthy effort to document the history and evolution of bluegrass and to promote the music to new generations.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024