Steve Martin: ‘What I found interesting is that our music has been standing completely on its own, and I can do whatever funny intro, and then when the song comes people take it completely seriously.’TheBluegrassSpecial.com Interview

‘I’m Really Enjoying Bluegrass’

Steve Martin Reflects on Life with Banjo In Hand, The Journey To The Crow and Rare Bird Alert and The Music’s Call

By David McGee

To those skeptics who think Steve Martin’s sudden emergence as a serious bluegrass and banjo aficionado is a dilettante’s work, consider the man’s history with the music and the instrument.

Born in Waco, TX, raised in southern California, his start in show business, of a sort, came as a Disneyland employee, when, as a 15-year-old, he entertained park visitors with magic, juggling, balloon animals and musical interludes played on the banjo. “I needed everything,” Martin said in a 2009 interview with the Guardian. “I did jokes, I did juggling, I did magic. I put the banjo in just to fill time, so I’d have enough to call it a show.”

The banjo remained part of his act as his career gathered steam. When he broke through in the ‘70s as a standup comedian, the banjo was still in the show, and though it was evident he was a fair picker, fans could be forgiven for thinking the instrument merely another prop, like the arrow through his head, so seamlessly was it woven into the fabric of his comedy via satirical tunes such as “Grandmother’s Song.” He would even roll out an original bluegrass tune from time to time, but audiences were always anticipating a laugh. His 1981 comedy album, The Steve Martin Brothers, featured one side of standup material, one side of live cuts with Martin playing banjo with a bluegrass band. No word on how much of that message got through to the masses.

Earl Scruggs and Steve Martin, ‘Foggy Mountain Breakdown,’ with Gary Scruggs (guitar), Vince Gill (guitar), Marty Stuart (mandolin), Albert Lee (guitar), Jerry Douglas (dobro)Come 2001, he was invited by Earl Scruggs to join in on a remake of the classic “Foggy Mountain Breakdown” on the Earl Scruggs and Friends album, and lo, the cut won a Grammy for Best Country Instrumental Performance. In 2007 he contributed his original song “The Crow” to Tony Trischka’s acclaimed Double Banjo Bluegrass Spectacular album, a triple IBMA award winner. (“The Crow” jumped off the album to become a hit bluegrass single, too--“my first hit single in thirty years [the other was ‘King Tut’],” Martin wrote in the liner notes to his The Crow album.) He also popped up unannounced at a Trischka “Double Banjo Celebration” at New York’s Cutting Room in which he more than held his own on stage with a stellar lineup of traditional and progressive bluegrass musicians, including Chris Thile.

This was but prelude to his next move: recording more original songs on an iPod, then passing them along to his friend John McEuen, founder of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, a roots musician nonpareil, and a confidante of Martin’s since their high school days together. McEuen fleshed out the arrangements. Then, with Martin financing everything himself (he wanted to avoid any record company interference), he and McEuen began the odyssey of recording, journeying to studios in Nashville, New Jersey, Hollywood, and Dublin, Ireland (where they recorded guest vocalist Mary Black) and along the way enlisting the services of some of the finest bluegrass-country-classical-roots musicians of our time: David Amram, Jordan Urbach, Stuart Duncan, Jerry Douglas, Matt Flinner, Trishka, McEuen, Earl Scruggs, et al., with guest vocalists including Vince Gill, Dolly Parton, Tim O’Brien and the aforementioned Mary Black.

The upshot was The Crow: New Songs For the Five-String Banjo. It won a Grammy. In case anyone wasn’t up on his history with the banjo, Martin opened his liner notes for The Crow with this historical perspective: “I have loved the banjo my whole life, and this album of fourteen compositions is the result of forty-five years of playing seriously, as well as playing around. Five of them were written over forty years ago; to compensate for a lack of professional instruction, I made up the tunes myself. The rest were written recently in a six-year burst of reanimation after Earl Scruggs asked me to play on his Earl Scruggs and Friends album.”

Steve Martin previews his show at Carnegie Hall for David Letterman, plays at the United Nations.In promoting The Crow and continuing his own education as a banjo player and bluegrass musician, Martin teamed up with the Steep Canyon Rangers for some selected dates and a short tour. When he was composing material for his next album, he asked the Rangers to join him on it, with co-billing. “They are their own band,” he says, “and I’m their celebrity.” Many of the songs--all originals again--were the product of Martin’s between-shoots downtime while filming his forthcoming The Big Year in western Canada, as he references in his detailed liner notes. (Let’s face it: the man likes to write, he’s good at it, and he’s making something special of the art of liner note writing in being so reflective about his own creative process.) Rare Bird Alert, the resulting album, produced by Tony Trischka, was a quick, clean process, according to all parties, with most of the recording being done in Asheville, NC, near the Rangers’ home turf, with jaunts to Amagansett, NY, to record Sir Paul McCartney laying down a compelling vocal on “Best Love” and out to Los Angeles to catch the reunited Dixie Chicks stealing everyone’s thunder with a mesmerizing meditation on lost love on Martin’s “You.”

Enough setup. Steve Martin and the Steep Canyon Rangers have a complete triumph under the belts in Red Bird Alert. The story would be incomplete without Martin’s own take on things, though, and he was more than generous in taking time to discuss the particulars of his liaison with the Rangers and the making of Rare Bird Alert. Without further ado…

***

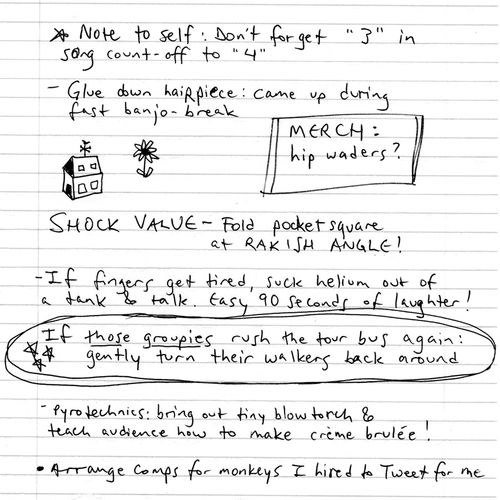

Confidential documents leaked on Steve Martin’s website regarding ‘Potential Ideas for New Banjo Show.’I must say that the show at Joe’s Pub was the single most unusual bluegrass show I’ve ever seen. Your comedy setups for the songs and your interaction with the Rangers brought a whole different kind of energy to the usual bluegrass set.

That’s interesting because I haven’t really seen a lot of bluegrass shows, so I don’t know what’s really going on out there. You know what I found interesting is that our music has been standing completely on its own, and I can do whatever funny intro, and then when the song comes people take it completely seriously. Like the song “You,” it’s a very earnest song, and I wondered if a funny intro would hurt the song. Not at all. It didn’t seem to matter at all. It has this long, slow banjo intro that’s a cue to the audience that it’s a serious song. So it’s really been good that way. I do feel like if it weren’t me up there the audience would be fine with the music, but I think they kind of expect a little humor. And it would be wrong not to do it. The worst cliché in the world is an actor who wants to be a musician--actually that’s the wrong thing--wants to be a rock star. Which is different from being a musician. And kind of turns their back on the audience. Takes it way too seriously. I take the music seriously, of course. But the show I enjoy because it’s a great break from the comedy to be able to go into the music.

I’ve seen you with the Rangers now three times, most recently before this at B.B. King’s. Although it was a Rangers show and you weren’t billed, you sat in for a good part of the set. Of the three occasions, at Joe’s you were more expansive in your relationship to the audience in terms of, again, the comedy bits, interacting with and talking to the audience as well as the band, more than you had ever been before. But Woody pointed out, those other two shows were really Steep Canyon Rangers shows.

Right. Where did you see us the first time?

It was also at Joe’s Pub, a year or so ago, and you weren’t announced as being on the bill, but the word must have got out because the house was packed. And the next night Dailey & Vincent came in and with a $12 ticket filled only about half the room.

Really!

‘The Crow,’ Steve Martin, Tony Trischka, Bela Fleck work out on the song recorded for Trischka’s triple IBMA award winning Double Banjo Bluegrass album.The next time Dailey & Vincent came here, they played the Living Room, which is less than half the size of Joe’s Pub, and with a $10 ticket still didn’t sell out the room.

I’m ashamed of New York. New York should be more aware of this music. That’s sort of why I created my banjo award [Ed. note: Martin and his hand-selected board--which includes Bela Fleck and Tony Trischka--each year award a $50,000 prize to a deserving young banjo player, the Steve Martin Excellence in Banjo and Bluegrass] because I thought, These players are as good as any type of musician out there and they should be getting paid more. (Laughs) You know? That’s amazing--Dailey & Vincent. I can’t believe that. I really can’t believe that. I remember about five years ago--or more, I can’t remember dates anymore--I saw an ad in the Times or somewhere, and it said, “Bluegrass Festival,” in New York. I thought, Oh my God, I hope I can get a ticket! I figured it would be in like a two-thousand seat concert hall, and I was stunned to find it was in a two-hundred seat nightclub that was three-quarters full. They had twenty acts over two or three days. That’s where I saw Valerie Smith, she was really good.

Steve Martin awards his Excellence in Banjo and Bluegrass Award, and $50,000 check, to Noam Pikelny, on the Letterman show. Pikelny later joined the Punch Brothers.What I was thinking about at the Joe’s Pub show as it rolled on was that the only thing I could think of in the bluegrass realm that it rivaled was The Robber Bridegroom, on Broadway in 1976. It was a bluegrass Broadway musical. Didn’t last very long and did go out on the road, but a guy who was in the onstage band was someone you know well, Tony Trischka.

Was he really? I’ll have to ask him about that.

It had some wonderful songs. It was written by Albert Uhry and Robert Waldman. Tony was part of the bluegrass band in The Robber Bridegroom.

There was another Broadway show that used a bluegrass band and it was called Fool Moon. Bill Irwin and the Red Clay Ramblers. Loved that. Loved the show and loved the music.

Before we get to the album itself, let’s go back--all the way back to your days at Disneyland when you were 15. Even then the banjo was part of what you did. Based on what I’ve read you used the banjo at that point mostly as a prop--you were just trying to entertain people any way you could.

Yeah.

You mention in the notes to the song “Hide Behind a Rock” on Red Bird Alert--and you mentioned it from the stage at Joe’s, too--about hearing that 1963 Flatt & Scruggs at Carnegie Hall album, and specifically the “Fiddle & Banjo” tune by Paul Werner and Earl Scruggs, when you were 17. What impact did that album have on you at the time? And in a sense are we here talking about your work as a bluegrass musician because of what that album did to you back then?

There were many apocalyptic moments that got me into the banjo. That record was maybe the third or fourth punch to the face. It’s hard for me to remember in what order things came, because I think, first, there was just regular old Kingston Trio strumming and entry level three-finger picking. But then I got into Earl Scruggs really fast, but I don’t know if it was that particular record, because I also had Foggy Mountain Banjo. And that record was just banjo, all Earl Scruggs. So that record was in there too. I think the Flatt & Scruggs at Carnegie Hall was like the second record I got. But Foggy Mountain Banjo was the first real getting into it.

And did those records lead you into studying the banjo more? Did you go back and try to find out where it started, who were the most famous practitioners? Did you get into it in that way?

I did read about it. I got Pete Seeger’s book, “How To Play the Five-String Banjo.” There was some banjo history in there. And Earl Scruggs’ book had some information. I don’t really know. I didn’t become a historian of it, no. But I knew about Joel Sweeney. I remember reading that Joel Sweeney--I think all this has been disproven now--had added the fifth string in about 1855 or something. In my adult life I was in London and went to the Victorian Albert Museum. I saw a five-string banjo there dated about 1820 (laughs). I’ve also learned, subsequently, that Sweeney was a major force and was supposedly a great, great five-string banjo player. I don’t know when the four-string took over, but it’s interesting that it took over right when Gibson started making great banjos in the teens and ‘20s. (laughs) They didn’t start making five-strings again until the late ‘30s. But I’m not really a banjo historian.

Earl Scruggs and Lester Flatt, ‘Cumberland Gap,’ from the Foggy Mountain Banjo album.The next step for me, after inundating myself with Scruggs style, and also the Dillards--the Dillards were in there; Marshall Brickman and Eric Weissberg--you know that great record, New Dimensions In Banjo and Bluegrass? There was also Bill Keith and Jim Rooney--very important. That’s where I first heard the Keith style. But there were these other records, banjo compilation records, with 20 different artists playing like 30 different songs. And there were a million different styles I had never heard before. When I started hearing clawhammer--this is about three years into playing--I thought, Uh-oh, I’ve gotta learn that style. And I still wasn’t very good at three-finger, and I realized I had to learn it. I’m so glad I did, you know. I really like the music that was on those compilations records, because it was completely different than Scruggs, than most folk music; it was all kind of self-taught people, you could tell--not self-taught but self-styled people. And I really like that--Billy Cheatwood, Dick Weissman, lot of different people.

What was it about the music that you found so interesting? Why did bluegrass draw you in, given all the other exciting music around in our youth?

Well, that’s a good question and all I can tell you is it was its sound. Now why it was its sound, I don’t know. But I was around the guitar, I was around piano, I was around reed instruments. I wasn’t around music that much, but I just loved it. It was like a magic trick, I guess--I was into magic. I was also into--well, when we saw the Dillards, to me Doug Dillard was a star. When he stepped up to play, he was the star! When you realized it could be learned--when you break it down into patterns and rolls, things like that--that there was a way in--I don’t know, I just loved it. There’s two things to be moved by in the banjo: one is its speed, and one is its emotion. And the banjo is rich with both of those.

I have a banjo compilation album that features some old tunes along with newer ones written by some of the artists on the album. One of those artists is Mason Williams, who is best known as a guitar player, specifically for “Classical Gas.” You were a writer on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour when he was the show's head writer. Did you talk to him about music while you were working together?

Oh, yeah! He didn’t play much banjo. He’d had “Classical Gas” as a hit, but you know John Hartford was on the show. We did a bit once where there were five banjos on the stage--Larry McNeely played, I played, John Hartford played, I can’t remember who the other two were. There might even have been a four-string banjo. Guy named Jerry Music, and he had an act with his wife Myrna Music. Later, on Rhoda, he was the voice of the doorman and he changed his name, for purposes of numerology, to Lorenzo Music.

Steve Martin and the Steep Canyon Ranger, ‘Best Love,’ from Rare Bird Alert, vocal by Sir Paul McCartney. Cello part written by the Rangers’ Nicky Sanders.On to Rare Bird Alert, then. One of my favorite songs is “Best Love.” It sounds like it might have been one of the great lost cuts off Rubber Soul. Again, referring to your notes, you said Nicky Sanders of the Rangers wrote the cello part. At the time he was writing the part, did he know that Sir Paul was going to sing this song? The sound of that arrangement so evokes the Beatles of the Rubber Soul/”Eleanor Rigby” era.

Yes, we did know. We did know. But, what’s interesting is when they came up with the background vocals that are sort of Beach Boys-ish--“you are my best love”--we didn’t know. I thought that was very interesting. I was wondering whether Sir Paul would find the Beach Boy backups a little awkward. But no, he was completely charming. But Nicky did know. I mention in the notes that I saw him on a couch just writing these parts, and I thought that was very smart of him.

But you didn’t direct him to write a cello part.

No, no. He said, “I think I’ll write a cello part.” I said, “Good.”

Were you there when PauL recorded?

Yes, absolutely.

Did he nail it quickly?

I think his first instinct was, because he thought it was essentially a country record, to twang it up a bit. Of course that’s the last thing we should be doing. We just wanted him to be Paul McCartney, with a little English accent. Then that’s where he ended up, so it was fine. But the great thing was his enthusiasm. Even after ten takes, he would keep improving and getting more comfortable with the song, and we’d say, “We got it,” and he’d say, “No, let me take a couple more swings at it.” Or he’d say, “Let me do the whole thing again from the top, all the way through.” So he was completely enthusiastic. You know it takes awhile to get used to a song you’ve never sung before. He was completely generous with his time. He wasn’t just knocking it off; he was into it. And he’s doing the best he can for you.

Now did he record that with you guys backing him, or had you already cut the instrumental track?

We had cut our part, but that’s the way we would do it anyway. Then we flew into where he was in Amagansett.

And you mention in your note to “Northern Island” that several of the songs emerged when you were in Canada shooting The Big Year, and you had time to explore the western part of the country. I’ve been there, I’ve been on up to the Arctic, I know what you were seeing. Was it simply the beauty of the land and the call of the wild, shall we say, that summoned the muse? Why did that experience produce so much new music?

Mmmmm, well, I wish I could say that. But it’s more like it was written in a condo in Vancouver. It’s actually having the time. You know, a movie set can be deadening. I came up with “The Great Remember” there--I forgot about that. That’s just noodling on the banjo, you know. I think I was watching a hockey game at the time. These are unromantic stories, but you are inspired by it. We were in the Yukon. On “Northern Island,” at the end when it goes into that major section, it just always reminded me, as I say in the liner notes, of a dawn, Arctic daybreak, which reminds me of the paintings of Lawren Harris, the Canadian painter. And I also wanted to pay tribute to the time I was there with these songs--“Rare Bird Alert,” “The Great Remember,” “Northern Island” and one other. But the fact that they all came from that time there must mean something. And we were out a lot in the country. Usually on your time off you’re not sitting in the country, you’re sitting in a trailer. Or a condo. But it’s hard to say what actually influences you. When I think of that movie and think of these songs, I instantly think of the Yukon when we were there. “Northern Island--I think of the Yukon; “Rare Bird Alert”--I think of a lot of scenes from the movie. I don’t think of the condo. Let’s put it that way.

Steve Martin and the Steep Canyon Rangers, ‘Jubilation Day,’ from Rare Bird Alert. Breaking up is easy to do.Also referring back to your notes, regarding “Jubilation Day.” In this song you speak the unspoken truth that breakups can be a positive experience. But I note that your vocal parts on that song are more in the goodbye-and-good riddance realm as opposed to, as you write in the notes, “an infusion of oxygen, spring and wonder.” Did something go awry between concept and execution?

Well, I’m not referring to anything specific. The character who’s singing that song is singing to that person, you know. (laughs) “I’ll be over you by lunchtime.” I don’t know, maybe another artist might interpret it differently, but it’s hard to say the line “I’ll be over you by lunchtime” another way, for me; or “cheatinpsychodishthrowinho.nut.” (laughs)

And I have to note an interesting thing in the sequencing that “Jubilation Day” is followed by an instrumental, “More Bad Weather On the Way.” People like me who like to see patterns and find messages even where there are none, that’s some enticing sequencing.

Well, I never thought of that. We always try to sequence it musically--hard driving bluegrass followed by a clawhammer. But you’re right.

I have to congratulate you, too, for reuniting the Dixie Chicks on “You,” because they’re great, and they’re great on this song. But from your notes it sounds like the song began as one thing and evolved into what we hear now as this melancholy, very moving memory of lost love. Is that what happened? And how did you arrive at inviting the Dixie Chicks to sing it?

To answer part one of the question, I didn’t know what it was. It was a series of chords that I liked. The more I played with it the slower it got. It’s like one day you’re sort of playing it along, playing it along, and probably what happened is one day I just started playing it slower and went, “Oh. It sounds better that way.” Eventually the song tells you what it is--you know that cliché. The Dixie Chicks came about in a very professional way--my publicist was working with their publicist, or knew someone connected with them and said, “What about the Dixie Chicks for one of the songs on your record?” I said, “Fantastic.” It was as simple as that. They liked the song and agreed to do it. They were delightful. I didn’t know if they were actually together, but somebody suggested it.

Was this a similar thing to the Sir Paul recording in that you cut it, and then they did their part?

We laid down the track and we actually flew to where they were in L.A. to record them.

‘The heart takes time to heal’: Steve Martin and the Steep Canyon Rangers, ‘You,’ from Rare Bird Alert. A Martin-penned meditation on lost love, inestimably beautiful as rendered by the Dixie Chicks.You had mentioned early “The Great Remember” as being something that developed as you were noodling around during the movie shoot in Canada. But it is dedicated to Martin Short’s late wife, Nancy. Based on your notes I guess it wasn’t consciously written in her memory, but like some of the other songs on the album developed after you came up with a basic structure. Does it turn out to reflect something about who she was, or is it more your musical eulogy for her?

Yeah, more the latter, because it was already underway when she died. She loved this kind of music. She was Irish, and she loved Irish folk music and I’d make compilations for her, like Mary Black and those great Irish folk singers and folk songs, and she loved that. It’s kind of a strangely sad song but also kind of noble--

Right. It has a lift about it.

Yes! And that’s the kind of person she was. She was a very energetic person. I think she would have liked the song. So it came at the right time, and I wanted to dedicate it to her. I don’t mention that on stage. It’s for the record. Martin Short’s life is not for use in my stage material.

Steve Martin, ‘The Great Remember (For Nancy),’ his musical elegy to Martin Short’s late wife included on Rare Bird Alert. ‘…kind of a strangely sad song but also kind of noble…,’ Martin says. Live at Joe’s Pub, March 15, 2011.You’ve worked with two great musicians as producers on The Crow and Rare Bird Alert, in John McEuen and Tony Trischka, respectively. Can you pinpoint what each of them did in their roles to help you realize your vision for these records?

Absolutely. John is one of my oldest friends. Met him in high school. He was crucial in teaching me the banjo. I’d meet him at his house and he taught me a lot of licks, he showed me a lot of different tunings. I play in a lot of different tunings. This is a strange metaphor, but I have a lot of paintings, and when a painting hangs in a place for a long, long time, you stop seeing it. When I re-hang the paintings I see them all anew. When I start to write a song and play in a different tuning, new things come out. And I like that. So he was very important.

When I first thought of The Crow I was first talking to Tony Trischka. I paid for The Crow myself. I realized I had enough songs, and I didn’t want to make a deal with a record company and have them say, “What is this?” You know? So I just booked a studio and I asked Tony and Pete (Wernick) and John to produce. But really I didn’t know what a producer did. And John came in and started twiddling the knobs and he’s the one who actually edited it. So he became the default producer of that, and he did a great job, obviously.

Tony had hired the musicians on The Crow--the basic four was Matt Flinner on mandolin, Russ Barenberg on the guitarist, Skip Ward on bass and then John brought in Craig Eastman on fiddle. Later John added a lot of musicians--Stuart Duncan, Jerry Douglas, all these great players. But I always felt a little bad that Tony and Pete sort of got aced out a little bit.

The Crow is a very produced record. This time I really wanted to make a band record. So I asked Tony if he wanted to do it. The two styles are completely different in that Tony listens to a band and makes a band record. John is more like a Beatles producer; Tony is more like a band record producer. That’s the difference. They’re all listening for the same thing, though, to make the best record possible.

Were you surprised The Crow won a Grammy?

(pause) Yes. (laughs) I go back further than that-- I was surprised it was received well and that it sold a lot. That it did well at all.

Did that change your thinking about moving forward as a musician?

Oh, yeah. Yeah. But the main thing that changed my thinking about moving forward was the stage show. Getting past being a novice musician on stage to being a professional musician on stage over the course of a year. And then having a real show develop out of it, and finding that people really like it, even people who don’t know what bluegrass is. They really like it. I can tell. When we play a place like Spokane, and we sell two thousand seats, and I know that a thousand people aren’t hard-core bluegrass fans--at least a thousand of them--and they’re leaving just enchanted by listening to six musicians play at a really high level. Or at least five of them.

The woman behind me in line at Joe’s Pub before the doors opened was on the phone with her daughter saying, 'We’re here to see Steve Martin play the banjo.' Nothing she said indicated she had a clue as to what bluegrass music is. But she had a great time at the show--I could see her from where I was standing at the bar--and when she left she still didn’t know who Bill Monroe was but she knew about bluegrass.

Right. You know, that venue is not exactly the type of place we’ve been playing. We’ve been playing these really beautiful concert halls, where people are quiet. They can really hear every instrument and they’re listening as though it were a concert, which I really like. They’re just as enthusiastic, if not more so, than a blasé nightclub crowd.

Is that distracting for you when the crowd is eating and drinking, more vocal between songs?

It’s not, because I’ve done everything in my life. I just go ahead, it’s whatever. But still, the concert crowd is ideal for listening, and for comedy, too, by the way.

Steve Martin and the Steep Canyon Rangers close their March 15, 2011 show at Joe’s Pub with a near-nine-minute version of ‘Orange Blossom Special,” which is dominated by fiddler Nicky Sanders’s electrifying solo turns. Seeing is believing, and it must be seen to be believed.That’s interesting about your stage show and you feeling like a novice musician and moving up from there. Obviously you’ve had a career as a standup, you’re used to being on stage, but I guess coming out with a banjo and basically having to carry the show, that’s a different deal, huh?

It is, yeah. I’ve been doing this now for just a little over a year. I had never done a full music show in my life. The most I had ever played on stage was two songs. I didn’t even know if my fingers could sustain that long, you know. Obviously, they can. I didn’t know if you could have a funny intro to a song. I remember the first show we played was at the Asian Society downtown. There’s a tiny museum, it seats 75 people, they wouldn’t let us use any mics. My eyes were just glued to the neck; I didn’t want to make any mistakes. But the more relaxed you get the better you play, the more carefree you are. I’m finding that place now, and it’s really, really nice. You really concentrate on making music, not making mistakes.

There’s a great chemistry between you and the Rangers on stage. There’s not only a lot of respect but a wonderful musical conversation that goes on on the stage, and clearly in the studio as well, on this record. What is it about them that makes them an ideal band for you to work with?

First of all, we all love to rehearse. We all love to do our best. Nobody says, “Oh, come on, let’s go home.” When we’re done we always remind each other of something--“Let’s do that,” “Let’s keep that.” We’re playing Vegas at the end of April and we’re going in a day early just to run over the show, to go over the music and get everything right. I think we’re all excited by this album. I think they’re getting a lot of benefit for their own group. I think that excites them. They’ve never been on TV, and now they’re getting on TV. It’s a big thing for them. I always try to make it very clear that they’re not my band--they are their own band.

There’s a bit you did at Joe’s Pub as the show goes on when you ask each Ranger how long he’s been playing his instrument. The first one was with Mike, the mandolin player, who answered “14 years.” Your response to that was a silent stare, which got a big laugh. That was one of three things that happened in that moment. The other two were your silent stare basically communicating the idea, 'Then what am I doing standing on stage with you?'; and the audience learning how long and hard these guys have worked to attain the level of artistry they have achieved.

Yeah, Nicky Sanders has been playing 25 years, and he’s only 30. It’s a perfect balance with us. I can play the arrogant Hollywood entertainer and they can play these homespun guys--I can’t explain it but it works particularly well. My favorite line in the show is when I introduce “Jubilation Day” and say, “Guys, is there anyone in your lives that you would like once and for all to be finally rid of?” And they just stare at me.

Steve Martin and the Steep Canyon Rangers, ‘Atheists Don’t Have No Songs,’ from Rare Bird Alert. Live at New Orleans Jazzfest 2010.You also spoke from the stage at Joe’s about various bluegrass magazines referring to you as an “ambassador of bluegrass.” Woody and I discussed this, and I know from that that he and his fellow Rangers really do feel a sense of mission about bringing this music to a wider audience and dispelling stereotypes about it, In a sense you and I have already discussed this, about the woman in line who said 'I’m here to see Steve Martin play the banjo,' but do you share that sense of mission?

Well, I didn’t at first, because I just didn’t think about it. But now I do. I don’t feel it’s my mission, but I feel it’s a default position, a byproduct. And now I think, Well, we’ve played on Letterman, we’ve played on The View, and we’re gonna play on Ellen, we’re gonna play on Conan, and I can’t think of any other bluegrass bands that do that. Alison Krauss, maybe. I guess I am, accidentally, some kind of someone who’s bringing it to wider exposure. But this happens every once in awhile. Earl Scruggs brought the banjo to The Beverly Hillbillies and it became a big hit, then brought it to Bonnie & Clyde in “Foggy Mountain Breakdown.” Periodically there’s a banjo breakthrough to the general public.

By the way, you played with Earl Scruggs. Did he give you any tips on playing the banjo?

Oh, I taught him a few things. He taught me how to play “Sally Goodin” when I was about 20.

About you songwriting process. Are you constantly developing riffs and ideas and putting them down and developing them. From your notes it sounds like you’re constantly composing.

I go into different periods to do that. I’m actually writing music for an animated film. With that you only need little feeds; you don’t need a completed entire song. And every once in awhile I come up with a song and write it down. If you do that twelve times in two years, you’ve got an album. But they have to be good. But we do have about four new songs already. I’m really enjoying bluegrass.

Has the success of your bluegrass albums and the critical acclaim that has come with them increased the value of your Gibson Florentine banjos that a Nashville dealer told you a few years ago were worth maybe $8,000 each, as opposed to the $200,000 each those of Earl Scruggs are worth?

I think they’re worth about the same! I don’t really play them on stage anymore. I’ve got this new Gibson flat-top that I play now. I do play one of the Florentines on The Crow. It’s a sharper sound. I’ve got used to the flat-top sound. I play four different banjos on stage, as you saw.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024