Ferlin Husky: ‘I’m making a hit record.’Gone

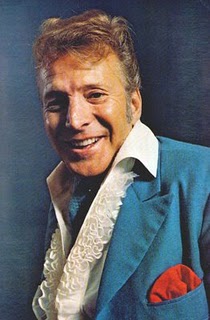

Ferlin Husky

December 3, 1925-March 17, 2011

As Terry Preston, he landed a recording contract with Capitol Records and then promptly reverted to his birth name, Ferlin Husky (he was born Furland, in Cantwell, MO, but his name was misspelled on the birth certificate), in which incarnation he made a chart topping debut with Jean Shepard on “A Dear John Letter” in 1953 and continued to have chart hits—twenty-four Top 20 singles, including two more number ones—between 1953 and 1975. He also developed a comic persona as gum chewing hayseed Simon Crum, who became a two-time chart sensation with a number five single in ’55 with “Cuzz Yore So Sweet” and a number two single in ’58 with “Country Music Is Here To Stay,” the latter expressing a sentiment Husky could get behind, as he was among the most successful country artists bucking the rock ‘n’ roll trend that was marginalizing country in the pop mainstream.

Ferlin Husky and Jean Shepard revisit their 1953 classic chart topper ‘Dear John’ in 2000—a great momentBut it was the Ferlin Husky of 1957’s smash heartbreak song “Gone”—ten weeks at number one, crossing over to number four pop—and of the upbeat gospel tune “Wings of a Dove,” a 1960 number one—a ten-week run at the top for this one, too, and a number 12 pop tune to boot--who became the big star among his three personas (four, actually, counting a brief turn as Tex Terry in the earliest days of his career). The irony of his 1957 breakthrough with “Gone” was twofold: his first run at “Gone,” in a spare, traditional country arrangement in 1952, was a bomb, but, though a traditionalist himself, Husky insisted on re-recording it in an expanded arrangement featuring additional musicians and some decidedly non-country touches—such as mezzo-soprano Millie Kirkham--in the soundscape. Legendary Capitol producer Ken Nelson bristled at Husky’s adventurous approach and at the costs incurred in realizing it.

"We had the Jordanaires on there as a vocal group, and Grady Martin on vibes, and a ton of people in the studio," Husky told the Nashville Tennessean in 2009. "The producer, Ken Nelson, got upset. He said, 'If one more person comes through those doors, the session is off.' And then here comes Miss Millie Kirkham to sing the soprano vocal part."

Because musicians and singers were paid at union scale, recording expenses mounted with each added sideman.

"He said, 'You're going to cost me my job,'” Husky said in the Tennessean interview. "In the middle of the song, I stopped the band and sung this 'Ohhhh' part, and Ken said, 'What in the world are you doing?' I said, 'I'm making a hit record.' And that's what we did."

Ferlin Husky, ‘Gone’ #1 for 10 weeks, 1957, featuring mezzo-soprano Millie Kirkham, the Jordanaires, and Grady Martin on vibes.Certified gold as a million seller, "Gone" appealed to teenagers as a slow-dance song; in fact, it was one of spate of hit country-pop fusions arriving in 1957 and early 1958 as Nashville artists scrambled to respond to the onslaught of rock ‘n’ roll with Sonny James’s stark “Young Love,” George Hamilton IV’s moody “A Rose and a Baby Ruth,” and Marty Robbins’s “White Sport Coat” (written by Burt Bacharach and Hal David, recorded in New York and produced by Mitch Miller). The success of “Gone” won Husky a stint as a summer replacement host in 1957 on Arthur Godfrey's CBS TV program. The singer played himself in DJ Alan Freed's 1957 film Mister Rock and Roll and had bit parts in 18 other movies. He also hosted his own TV show for a short time.

Husky’s biggest success came with 1960’s “Wings of a Dove.” In an attempt to widen the gospel song’s appeal, the producer deleted a verse that made direct references to Jesus, although the biblical imagery was still implicit in the lyrics.

Ferlin Husky, 1960’s ‘Wings of a Dove,’ Husky’s third #1 single, and second as a solo artistFerlin Eugene Husky was born Dec. 3, 1925, in Cantwell, MO, a town that has since been incorporated into Desloge. In his youth Husky’s family moved frequently trying to make ends meet, and he lived, at various times in Flat River, Bonne Terre, Stony Point and Hickory Grove, where he attended elementary and high school. He learned the basics of guitar from an uncle and played in churches and in amateur competitions around his home town area. After dropping out of high school, he moved to St. Louis, where he worked as a truck driver and steel mill worker while performing in honky tonks at night.

After World War II broke out the teenager Husky joined the National Guard and was mobilized into the Merchant Marines. He was in Army Transport and the ship on which he served as a merchant seaman was involved in transporting troops across the English Channel to Normandy for the D-Day invasion. Over the course of the war he remained in Army Transport, but served in three branches--the Merchant Marines, the Army and was discharged in 1946 as a member of the Coast Guard--all that time serving aboard ships.

Ferlin Husky as Simon Crum offers his impersonations of Tennessee Ernie Ford, Webb Pierce and, in duet, Kitty Wells and Red FoleyDuring his time in the service, Husky developed his Simon Crum character, based on a Missouri neighbor of his named Simon Crump, whose personality quirks and hick accent became more pronounced with each new tale. During WWII, Husky regaled his shipmates with tall tales about Crump.

“Most of my shipmates were Yankee boys,” he told Country Music People magazine. “They would say, ‘C’mon, Country, tell us some more of those Simon stories.’”

When Husky returned to Farmington, his uncle, Everett Wilkinson, was operating W&W Welding Shop. Always encouraging his nephew to pursue a career in country music, Wilkinson sponsored Husky's early morning radio show on KREI in Farmington.

"It was just me and my guitar," Husky said. "I was performing under the name Tex Terry at that time."

The radio show lasted only a couple of months, but it gave Husky exposure and also provided him with a valuable connection. Johnny Rion, a popular local musician, was managing KREI at the time and he and Husky would perform together in areas to the north such as Jefferson County and the St. Louis area.

Husky’s path then took him to the thriving country music scene developing in southern California. Needing money, he took a job working in the lettuce fields by day and playing honky tonks at night around Salinas. When Gene Autry’s comic sidekick Smiley Burnette came through to play the Big Barn in Salinas, an introduction was arranged and Husky was invited to tour with Burnette. Burnette then introduced Husky to Autry, who became a mentor to the young artist, to the point of giving him living quarters and teaching him the ins and outs of show business. While working as a disc jockey under the name Terry Preston (a name suggested by Smiley Burnette, on the theory that Ferlin Husky was not marquee friendly), Husky began his recording career in 1948 for Bill McCall’s Four Star Records. As a Four Star artist Terry Preston cut nine singles, none successful. In 1951 he replaced Tennessee Ernie Ford in the cast of Cliffie Stone’s Hometown Jamboree TV show, and Stone, impressed with the emotion, warmth and unusual trill in Husky’s voice, brought him to Capitol Records the following year.

‘Daddy, why did you do this to us? How come you run us to the ground?’: Ferlin Husky, ‘The Drunken Driver,’ 1954, in which an inebriated father runs down his own kids. Husky’s most bizarre recording.Upon signing with Capitol, Husky returned to using his real name for his career launching duet with the promising Bakersfield, CA, vocalist Jean Shepard on “Dear John.” A sequel recording, “Forgive Me John,” peaked at number four country. Four Husky solo singles followed, three of them rising into the Top 10, another peaking at #14, but setting the stage for “Gone.” After “Gone” began dominating the charts, Husky toured extensively throughout the southern states. One of his opening acts was a young Tulepo singer signed to Sun Records in Memphis, Elvis Presley. Husky became friendly with Elvis and his parents, Vernon and Gladys. While stationed in Germany during his years in the Army, Elvis continued to correspond with Husky.

In August 1977, Husky was in a Minneapolis hospital after undergoing heart surgery when a friend read him a list of people who had called with get-well messages. One of those left his name as Vernon. Thinking it was his cousin Vernon, Husky was told it was, instead, Vernon Presley.

"I don't remember the date of the surgery," Husky said in a 2004 interview with Larry Sigman of the Park Hills, MO, Daily Journal, "but I will never forget the date they took the stitches out. I was laying there on the table and there was small, black and white television monitor up on the wall. All of the sudden they flashed a news bulletin on the screen. Elvis had died. It was Aug. 16, 1977, the day I got the stitches out.

“You don’t know how I felt. He was a good friend and a good person. It really took something out of me.”

Ferlin Husky and Patsy Cline, a little holiday cheer in ‘Let It Snow,’ from Ozark JubileeOne of the first country stars to be honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, Husky liked to joke that “people have walked all over me.” He also has a street named after him in a city park in Leadwood, MO. On May 23, 2010, he was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame.

Husky had a history of heart trouble. Following his heart surgery in Minneapolis in 1977 he briefly retired. In 2005 he had another heart operation, and in 2009 was hospitalized for congestive heart failure and pneumonia. On March 8, he was admitted to a coronary care unit of a Nashville area hospital and died there of congestive heart failure on March 17.

Husky was married four times. He is survived by six daughters: Donna Denson and Julie Smith, both of Gallatin, TN; Dana Stone, Westmoreland, TN; Alana Jackson, Hendersonville, TN; Jennifer Lane, Murfreesboro, TN; Kelly Wiles, Canada; and two sons, David, Post Falls, IO, and Terry, Amarillo, TX; and 11 grandchildren. A son, Danny, died in a traffic accident in 1970.

***

Ralph Mooney: ‘A steel guitar hero and a legend to us all,’ says Marty Stuart.‘I Put It In There, But It Comes Out Hillbilly’

Ralph Mooney, Greatest Steel Guitar Player Ever

September 16, 1928-March 20, 2011

If Ralph Mooney had done nothing more than stick out the Dust Bowl years in Oklahoma in his youth, he would have had plenty of tales to tell. As it happened, he left Oklahoma in 1940, joined his sister in California and eventually helped changed country music history as an instrumentalist and as a songwriter co-wrote one of the genre’s greatest songs. Beginning about a decade and a half after his arrival in California, Mooney’s steel guitar work helped define not only the sound of some of the era’s greatest country artists--Wynn Stewart, Merle Haggard, Buck Owens, Waylon Jennings--but also of a new, harder-edged, rock-influenced style of country centered in Owens’s home base of Bakersfield, CA. In his Nashville Skyline column of March 24 at cmt.com, Chet Flippo, eulogizing Mooney as “the Greatest Steel Guitar Player Ever,” recalled his introduction to Mooney in the early ‘70s. On assignment for a magazine, Flippo was embedded on the Waylon Jennings tour bus--a vehicle, Flippo notes, that was not one of today’s luxury liners but rather a strictly utilitarian vehicle harboring musicians living a Spartan lifestyle: “It was hard traveling. Long drives between gigs, with Cokes and cigarettes and Snickers candy bars for a late breakfast/lunch and with weed and beer and baloney sandwiches for dinner--if there was dinner.”

Fully versed in Mooney’s history but never having seen him in person, Flippo was surprised to find the musician “an amiable, soft-spoken man who looked perhaps more like a bank teller than a star sideman.”

When the music started, though, Mooney was in his element, and in command.

Flippo: “In those crowded, smoky, drunken, raucous honky-tonks, Moon's ‘Moon shots’ of clear and piercing steel guitar notes shot through the heavy air like swift steel-tipped arrows. He was the perfect foil to Waylon's own fierce Telecaster twang style of picking, and their blend of sound together rode clean and clear above the intense crowd noise. What a perfect honky-tonk sound that was. That was true metal rock 'n' roll, as only the best country musicians can play it and experience it.”

Merle Haggard, ‘Mama Tried,’ Ralph Mooney on steelAfter moving to California, Mooney learned to play guitar, mandolin and fiddle. After hearing a recording of “Take It Away” Leon McAullife’s classic “Steel Guitar Rag,” his life was irrevocably altered. Having never seen or heard a steel guitar to that point, he began emulating McAuliffe’s sound by using a knife on the strings of his flat-top guitar. From that inauspicious beginning he fashioned a legendary career. At his death from cancer on March 20, 2011 (in Kennedale, TX), Mooney was properly acknowledged as occupying the highest perch in his instrument’s pantheon, along with towering practitioners such as Pete Drake, Speedy West, Don Helms, Lloyd Green, Jesse Ashlock and Weldon Myrick. He broke into the big time as a member of Wynn Stewart’s band; added his distinctive crisp, melodic touch to some of Buck Owens’s pioneering Bakersfield Sound recordings and did the same for more artists than he could recall as a first-call session player for Hollywood-based Capitol Records in the 1950s and ‘60s, working studio dates with Rose Maddox, Bonnie Owens, Skeets McDonald, Jessi Colter, Donna Fargo—more than 70 artists all told. In addition to Stewart, a young Merle Haggard and Wanda Jackson benefitted from Mooney’s distinctive touch on their records. So influential and identifiable was his sound and attack in those days that country-rock pioneer Chris Hillman identified him in the Los Angeles Times as “one of the chief architects of the Bakersfield sound. Nobody played steel like Ralph. When Ralph took a solo, you knew it was all California.”

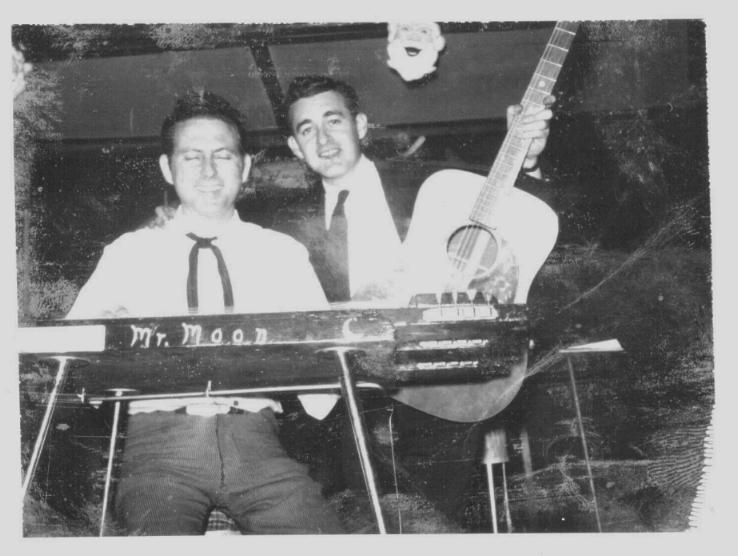

Ralph Mooney, ‘Mr. Moon,’ commanding the steel for Wynn Stewart in an undated photoIn addition, he dabbled in songwriting, and, with co-writer Charles Seals, came up with one of country’s greatest songs, “Crazy Arms,” memorably introduced in 1956 by Ray Price, who topped the chart with it and made its Texas shuffle sound his musical signature. Country music historian Bill C. Malone, writing in his essential Country Music USA book, describes “Crazy Arms” as “a refreshing reassertion of hard-core country music at a time of rockabilly ascendancy, and a vehicle for the introduction of Price’s shuffle-beat sound into country music.” The song has since been covered more times than Mooney could count. (It was also Jerry Lee Lewis’s first recording on Sun Records in ‘56, and was a Top 20 hit for Willie Nelson in 1979.) “It has been recorded by so many different people. I would starve to death if it wasn't for those royalty checks,” Mooney once said of “Crazy Arms.” He also wrote “Foolin’,” a Top 4 chart hit for Johnny Rodriguez in 1983 that was one of Mooney’s favorite records: “It was real country with fiddles and steel guitar. The way I like it.”

Wynn Stewart, ‘Falling For You,’ with Ralph Mooney on steelHe first played in several amateur bands and for a time worked for the Douglas Aircraft Company. After appearing with local band Merle Lindsey And His Oklahoma Nightriders, he joined Skeets McDonald's band with whom he made his first recordings. He refined his style of playing steel with the help of Texas Playboy Jesse Ashlock and for a time played a self-built steel guitar. In 1950, while he was a regular on Squeakin' Deacon's popular radio show, he first met Wynn Stewart and gained session work. He played on early Buck Owens' hits such as “Foolin' Around” and the career launching “Under Your Spell Again” and also played lead guitar on Stewart's first Capitol Records recordings.

Buck Owens’s career launching hit, ‘Under Your Spell Again,’ with Ralph Mooney on steelIn 1961, he moved with Stewart to Las Vegas and for two years worked there in Stewart's club. Merle Haggard was also a band member for a time and when Haggard made his first Tally recordings, Mooney played steel guitar on them. Stewart remained based in Las Vegas after Mooney returned to California, but the two continued to work together on occasion. He also worked on the road for a time with Haggard, but bowed out owing to his disdain for Hag’s heavy touring schedule. He did, however, contribute steel guitar to some of Haggard’s defining hits, including “Mama Tried” (those opening swoops are his), “Sing Me Back Home,” “Swinging Doors” and “The Bottle Let Me Down.” In the late ‘60s, he reunited with Stewart and stayed with him until Stewart's health forced him into retirement. In 1969, Mooney joined Waylon Jennings' Waylors, where he remained for more than 20 years. Later he continued to make appearances at special instrumental festivals or conventions and became noted for his lectures about and demonstrations of his favorite instrument.

Waylon Jennings and the Waylors, with Ralph Mooney on steel, on Austin City Limits

In 1968 Mooney tried his hand at a solo project with a so-so instrumental album, Corn Pickin’ & Slick Slidin’, with Telecaster master James Burton. “We had lot of fun, me and Burton,” Mooney told Gib Sun of the Nashville Tennessee Steel Guitar Association in a 2003 interview. “We'd go over to Burton's house every night and figure up four songs for the next day. It was a lot easier that way. We did 12, I think. It was a relaxed session. Of course, Burton pulled one on me. He was totin' in Dobro, totin' in the guitar, all kinds of guitars and stuff. He was charging them that..what do you call it? They pay you for carying your on own guitar. He got a lot of his money ahead of time.”

Mooney also recorded some instrumentals for Challenge Records, including the single “Release Me” b/w “Moonshine.” Both later appeared on 4 Star various artists albums, Country Love and Tennessee Pride, respectively. He may also be heard with the Waylors on the soundtrack album from the 1975 movie Mackintosh And T.J. (which starred Roy Rogers). In 1983 Mooney was inducted into the Steel Guitar Hall of Fame.

In his last big project, Mooney joined Marty Stuart and The Fabulous Superlatives on one of Stuart’s finest albums, last year’s Ghost Train (The Studio B Sessions). As many times as he had heard Mooney’s magic touch on country records, Stuart was still bowled over by what happened in Studio B, as he related on his website:

“Probably the most influential country musician that I've ever known is Ralph Mooney. Moon helped write 'Crazy Arms.' He's a steel guitar hero and a legend to us all. He played on most of Buck Owens' greatest recordings, and I think Merle Haggard would be the first to tell you that Ralph Mooney was instrumental in helping Hag develop his sound. Moon went on to work with Waylon Jennings during all of his glory years and helped Waylon define his musical legacy. Now I went to Texas to visit with Moon at his home when I was developing Ghost Train. We played music most of the afternoon in his garage, and he agreed to come to Nashville to record with me. Country music royalty hit town when Ralph Mooney showed up. Waylon used to introduce him in concert by sayin', 'Ralph Mooney is the most imitated steel guitar player in the world.’ And ol’ Waylon's words rang true when he performed the song that I wrote for the Ghost Train Sessions called 'Drifting Apart.’”

Marty Stuart coaxes Ralph Mooney into playing ‘Crazy Arms’ during the Ghost Train sessions. Photos copyright Adam Smith.Asked in the NTSGA interview to name about his favorite steel players, Mooney was typically humble in identifying his ideal as Curly Chalker, who played with Lefty Frizzell, Hank Thompson, was in the Ozark Jubilee and Hee Haw TV show bands, and also played non-country sessions, including Simon & Garfunkel’s “The Boxer.”

“Yeah! One of my favorite jazz players,” Mooney said of Chalker. “I had never heard nothing like that before. I was sitting out in the audience with my mouth open. He just knocked me out. Him and Thumbs Carlisle were jamming after the curtain went down at the Golden Nugget. I could see Curly’s feet. He was pumping them pedals. Knocked me out. He always was one of my favorite jazz players. I can’t play nothing like that. I put it in there, but it comes out hillbilly.”

***

‘Crazy Arms’ X 3

Ray Price’s original chart topping version of ‘Crazy Arms,’ 1956, ‘a refreshing reassertion of hard-core country music at a time of rockabilly ascendancy…’

Jerry Lee Lewis, ‘Crazy Arms,’ live in London, 1983, performs his first Sun record, released in 1956.

Patsy Cline’s Latinized take on ‘Crazy Arms,’ cut at her last recording session, February 7, 1963.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024